KEMAL DERVIŞ, Project Syndicate

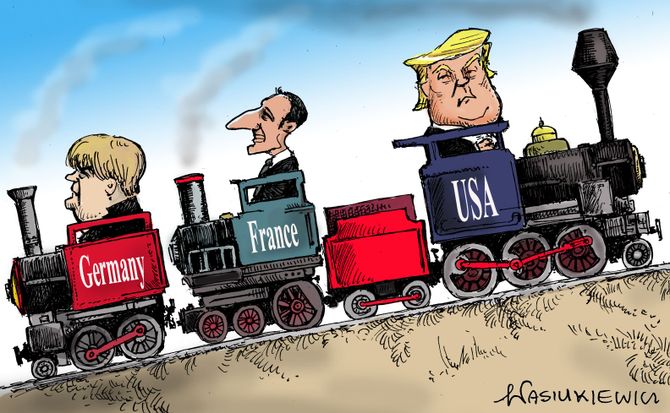

WASHINGTON, DC –La visite d’État du président français Emmanuel Macron aux États-Unis le mois dernier a été riche en contrastes. Malgré la cordialité des échanges, l’ordre du jour et le discours de Macron étaient presque diamétralement opposés à ceux du président américain Donald Trump. Macron devra toutefois relever un défi politique plus fondamental durant son mandat et la manière dont il s’y prendra pourrait montrer la voie à suivre pour la démocratie libérale.

S’adressant en anglais au Congrès américain, Macron a défendu un point de vue résolument internationaliste, appelant au renforcement des institutions internationales, au renouvellement de l’engagement en faveur d’échanges commerciaux basés sur les règles et à une adhésion sans réserve à la mondialisation. En ce qui concerne l’Iran, il a réaffirmé la nécessité de préserver l’accord sur le nucléaire conclu en 2015, un accord dont les États-Unis viennent de sortir à l’initiative de Trump, tout en appelant à le compléter sur des points qui ne sont pas inclus dans le texte actuel.

Macron soutient par ailleurs le projet de création de listes paneuropéennes pour les prochaines élections du Parlement européen en 2019. En tant que démocrate, il estime qu’une plus grande intégration de l’Union européenne va de pair avec le développement d’un espace politique véritablement européen.

A une époque où les motifs d’inquiétude ne manquent pas, qu’il s’agisse du déclin du libéralisme, de l’avenir de la social-démocratie, de la montée en puissance des nationalismes ou du rejet de la mondialisation, la position résolument internationaliste de Macron est remarquable. Il fait à vrai dire un saut dans l’inconnu en proposant une « nouvelle politique » pour l’Occident, un terrain qui n’est plus uniquement défini par la concurrence entre les grands partis du centre-droit et du centre-gauche. On peut toutefois se demander si le clivage traditionnel entre la gauche et la droite est vraiment dépassé.

Il serait erroné de décrire Macron, qui a été ministre dans le gouvernement socialiste de son prédécesseur François Hollande, comme étant simplement centriste. S’il a effectivement migré vers le centre, il n’a pas adhéré à l’un des petits partis centristes traditionnels, mais a préféré fonder son propre « mouvement » politique.

Dès le début, Macron a décrit ce mouvement, baptisé « En marche », comme n’étant ni de gauche, ni de droite, évitant toute référence au terme « centriste ». Aujourd’hui, il le qualifie comme étant à la fois de gauche et de droite, reflétant son ambition de rallier les électeurs du centre-droit et du centre-gauche traditionnels.

Si ce clivage gauche-droite devient de plus en plus flou, la question se pose de savoir ce qui le remplacera. Étant donné que la mondialisation est au centre des débats politiques dans la plupart des pays, l’on pourrait penser que la réponse est l’opposition entre les partis cosmopolites et les partis chauvins.

Dans cette optique, Macron est à la tête du mouvement pro-mondialisation (et pro-européen), tandis que les partis de l’opposition, qu’ils soient de droite ou de gauche, sont hostiles à une politique d’ouverture économique. Et, en fait, l’extrême-droite et l’extrême-gauche ont des positions économiques similaires.

Dans le même temps, les partis politiques de centre-droit et de centre-gauche existants – en France et dans les autres pays occidentaux – comprennent des factions tournées vers l’international et d’autres plus critiques de la mondialisation. La logique veut que si la mondialisation est bien en train de devenir le principal facteur de polarisation électorale en Occident, ces deux camps devraient imploser et former de nouvelles familles politiques.

S’il existe bien une tendance dans ce sens, je pense peu probable que le clivage traditionnel gauche-droite disparaisse. Les principaux partis continueront à débattre des enjeux importants, que ce soit la répartition des revenus, les régimes d’imposition progressifs et la portée et les objectifs de la politique sociale. La plateforme « mondialisation » ne suffira pas à elle seule à définir un grand parti politique.

Cela signifie que dans les années à venir, Macron devra s’aligner plus étroitement sur le centre-droit ou sur le centre-gauche. Les circonstances particulières qui lui ont permis de remporter l’élection présidentielle en 2017 – un centre-gauche discrédité et une candidate d’extrême-droite impliquée dans plusieurs scandales – ne se reproduiront pas. Il devra devenir un dirigeant internationaliste plus proche de la gauche ou plus proche de la droite.

Une seule de ces options semble viable. Les politiques habituelles des partis de centre-droit ne sont pas aisément compatibles avec une forte volonté d’ouverture internationale. Pour être acceptée, la mondialisation, dans ses multiples dimensions, devra être accompagnée d’une politique sociale modernisée qui apporte une aide efficace à ceux qui en ont besoin, particulièrement en cette période de perturbations économiques incessantes.1

L’ouverture économique impose une solidarité sociale. Cela ne signifie pas protéger des emplois spécifiques contre la concurrence commerciale ou les innovations technologiques. Cela signifie aider les individus à s’adapter aux changements constants et à fournir les ressources dont ont besoin les citoyens, telles l’éducation, des soins de santé abordables et des aides à titre transitoire. En bref, pour être largement populaire, un positionnement pro-mondialisation nécessite un nouveau contrat social – soutenu par des actions et des moyens financiers publics. Faute de quoi, il sera difficile de résister au chant des sirènes du néonationalisme.1

Tout en parachevant les nécessaires réformes fiscale et du code du travail, Macron devra relever ce défi. Dans le contexte du changement actuel de paradigme politique, ceux qui sont favorables à l’ouverture ne l’emporteront sur l’unilatéralisme nationaliste qu’en se donnant comme principal objectif une approche actualisée de la solidarité sociale.