Vice President, Cities & Public Services, Dassault Systèmes. He started his career as a research fellow at the French Institute of International Relations (IFRI), focusing on European security and transatlantic relations. He has worked for EADS-AIRBUS as senior manager in charge of international development. In 2005, he was appointed diplomatic advisor to the French Minister of Transport and Infrastructure, D. Perben. From 2007 to 2015 he worked for Alstom group, in the energy and rail transportation sector, in various capacities. In 2016, he joined the regional council of Paris Region as deputy director general and special advisor to the President, in charge of European affairs, international cooperation and tourism, until September 2019.

Tatiana Kastouéva-Jean

Research Fellow and Director of Russia/NIS Center of Ifri since January 2014. Before joining Ifri in 2005, she taught International Relations for the French-Russian Master at MGIMO University (Moscow State Institute of International Relations). At the beginning of her work at Ifri, she developed a rich expertise on issues linked to youth, higher education and innovation in Russia: she is the author of the book Les universités russes sont-elles compétitives ?, CNRS Editions, 2013. She currently heads the trilingual electronic collection Russie.Nei.Visions. She holds a degree from the State University of Ekaterinbourg, a Franco-Russian Master in International Relations from the University of Sciences Po and MGIMO University, and from the University of Marne-la-Vallée in France. In 2020, she published La Russie de Poutine en 100 questions (Paris, Tallandier).

Jean-Pierre Cabestan

Senior Researcher Emeritus at the French National Centre for Scientific Research (Centre national de la recherche scientifique), attached to the French Research Institute on East Asia (IFRAE) of the National Institute of Oriental Languages and Civilisations (INALCO). He is also Professor Emeritus at Hong Kong Baptist University. Prior to September 2021, he was Chair Professor of Political Science, Department of Government and International Studies, Hong Kong Baptist University. He was Head of the Department from 2007 to 2018. He is also Associate Researcher at the Asia Centre, Paris and at the French Centre for Research on Contemporary China in Hong Kong. Named Officer of the Palmes Académiques in 2018 and Knight of the Order of Merit in 2022, he has been a corresponding member of the Académie des sciences d’outre-mer (ASOM) since 2019. His main research topics include political, institutional and legal reforms in People’s China, Chinese foreign and security policy, China-Taiwan relations, the Taiwanese political system and China-Africa relations. His most recent publications include China Tomorrow : Democracy or Dictatorship? (translated by N. Jayaram; Lanham, MD, Rowman & Littlefield, 2019), and Facing China: The Prospect for War and Peace (translated by N. Jayaram; Lanham, MD; Rowman & Littlefield, 2023).

Josep Borrell Fontelles

Josep Borrell Fontelles is the High Representative of the European Union and Vice-President of the European Commission. He was a Minister of Public Works and Environment from 1991 to 1996, member of the European Parliament from 2004 to 2009 and its President from 2004 to 2007. Borrell became President of the European University Institute in 2010 and Jean Monnet Chair at the Institute of International Studies at Complutense University of Madrid. In 2018, he was appointed as Foreign Minister for the Spanish government and in 2019 High Representative of the European Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy.

Sweden’s Centrists Prevail Even as Far Right Has Its Best Showing Ever

By Christina Anderson and Steven Erlanger, The New York Times

STOCKHOLM — Sweden looked set for a period of political confusion after election results on Sunday put a center-right bloc and the governing center-left coalition neck and neck, while a far-right, anti-immigration party came in third — winning a higher percentage of the vote than ever before, but achieving less of a breakthrough than polls had suggested.

With more than 99 percent of ballots counted, the national election commission reported that the governing center-left Social Democrats had 28.4 percent of the vote, making it the largest single vote-getter, but handing the party its worst showing in decades.

The center-right Moderate party was next at 19.8 percent, while the far-right Sweden Democrats were running third, with 17.6 percent, up from 12.9 percent in 2014 but a less successful showing than many Swedes had feared. Some polls had predicted that the Sweden Democrats would come in second, with more than 20 percent of the vote.

The red-green bloc of center-left, leftist and environmental parties, led by the Social Democrats, had 40.6 percent of the vote. The center-right alliance, led by the Moderates, was just behind with 40.3 percent. The results mean neither bloc can command a majority in Parliament, and both have rejected the idea of any deal with the Sweden Democrats.

The campaign was unusually polarizing in a country known for seeking political consensus. The main issues were also the most contentious: immigration, crime, the welfare state and, after a summer of forest fires, the environment.

For some voters, the fierce debates were a welcome change.

“In Sweden we have been too afraid to discuss the issues,” said Anders Nilsson, 54, an I.T. engineer who voted for the Center party in Botkyrka, a diverse suburb south of Stockholm. “Now we dare to discuss tough questions.”

This election has been one of the most closely watched in Sweden’s recent history, with a focus on how the Sweden Democrats would perform given the rise of anti-immigration populist parties in countries like Germany, Italy and Austria.

“The world’s eyes are on Sweden and the path it takes,” Annie Loof, the head of the Center Party, said in a debate before the vote.

The Social Democrat prime minister, Stefan Lofven, who runs a minority government of the center-left, had warned voters on Saturday not to cast their ballots for what he called a “racist” party.

“This election is a referendum about our welfare,” he said. “It’s also about decency, about a decent democracy and not letting the Sweden Democrats, an extremist party, a racist party, get any influence in the government.”

Jimmie Akesson, the leader of the Sweden Democrats, told supporters on Saturday that the current government had “prioritized, during these four years, asylum-seekers,” listing failures to do more for health care, housing and pensioners. “Sweden needs breathing space,” he said. “We need tight, responsible immigration policies.”

The results on Sunday followed another recent European election pattern: the shrinking of mainstream parties of the center-left and the center-right as they lose votes to more extreme parties on both sides of the political spectrum, as well as to environmentalist parties.

In Sweden, this shift has raised questions about whether the main parties will keep their vows to have no dealings with the Sweden Democrats, or whether they will have to reach some understanding with the party, especially on crucial budget votes.

The main parties may try to negotiate some sort of grand coalition, but that would be unusual in Sweden, where minority governments are fairly common.

“This is a new situation for Sweden,” said Soren Holmberg, a political scientist who heads the SOM Institute, an independent research group at the University of Gothenburg. “What is pretty clear is that there won’t be a majority on either side, so it means we have to have a lot of negotiation between the blocs.”

About 7.5 million registered voters chose from almost 6,300 candidates for a four-year term in the 349-seat Parliament.

Arian Vassili, a 23-year-old engineering student who voted Sunday in Botkyrka, said he supported the Social Democrats. “This is an incredibly important election,” he said. “This is an election about values, how you view people, your fellow human beings and whether we are going to take care of each other.”

Maria Enberg, 42, a cook who lives in Botkyrka, said she had voted for the Center party. “The Sweden Democrats have become so big, and I really wanted to vote against them. I don’t want any racist party governing in Sweden.”

The Sweden Democrats’ rise began in 2010, when the party crossed the 4 percent threshold for Parliament seats, getting 5.7 percent of the vote. In 2014, its vote share rose to 12.9 percent, making it Sweden’s third-largest party.

The Sweden Democrats have greatly benefited since the migration wave of 2015, when 163,000 asylum seekers came to Sweden, about 1.6 percent of the population.

Under Mr. Akesson’s leadership, the party has tried to soften its image. It now uses for the party logo a floppy flower in Sweden’s colors of blue and yellow instead of a flaming torch, and the party insists that it will not tolerate racism. But it campaigned on keeping “Sweden Swedish,” cracking down on crime and questioning whether immigrants and Islam will alter the country’s identity.

As in Germany, stricter border controls have been introduced in Sweden, and the numbers of new immigrants has fallen steeply, to about 23,000 this year.

Image

But the political damage had been done, and despite a thriving economy and generally low unemployment, the Sweden Democrats argued that immigration should stop and that resources should go to refurbishing Sweden’s famous welfare state, which is strained by an aging population and the challenge of taking on migrants.

For those born in Sweden, the unemployment rate was 4.4. percent in 2017; for migrants, the number was 15.1 percent, according to government statistics.

During the campaign, the right-wing party spoke directly about traditionally taboo subjects like identity, Islam, integration and crime, winning supporters who felt the traditional parties had been reluctant to touch such sensitive issues. The party, along with the Left party on the other extreme, has benefited from a general sense of discontent and loss of confidence in the political system.

Li Bennich-Björkman, a political scientist at Uppsala University, said it was “sort of shocking” that the Sweden Democrats could come this far, but she noted that the party, which has disavowed its roots in the white supremacist movement, had transformed.

“I would say that the major part of their electorate are not racist and fascist,” Ms. Bennich-Björkman said. “They have managed very skillfully to transform themselves into a variant of the Social Democratic party, just with more nationalist ambitions,” she said.

The Social Democrats, who have dominated the country for a century, built Sweden’s welfare state. But their support has declined from 45 percent in 1994 to just over 28 percent on Sunday. The Left Party had 7.9 percent of the vote, and the Green Party 4.4 percent.

The Moderate party, led by Ulf Kristersson, leads the center-right bloc. He was chosen in October 2017 to head the party when his predecessor, Anna Kinberg Batra, resigned after suggesting that it might be possible to work with the Sweden Democrats. In its alliance, the Center Party won 8.6 percent of the vote, the Christian Democrats 6.4 percent and the Liberals 5.5 percent.

On Sunday night, Mr. Kristersson called on the prime minister to resign. “This government has run its course,” he told a party rally.

With the two blocs so close to each other, negotiations over forming a government are expected to be drawn out. “Usually we are quick in forming a new government,” said Mr. Holmberg, the political scientist. “This time it could drag on for weeks or months.”

Both centrist parties have moved to the right under the pressure of the Sweden Democrats and have promised tougher policies on immigration, the integration of refugees and crime.

Daniel Suhonen, the head of Katalys, a trade union research group, said he saw “very sad” parallels in the United States for the Sweden Democrats’ rise.

“They had a clear answer, like Trump,” he said at a Social Democrats event. “They said all the problems in Sweden are created by an elite that is corrupt and ruined the country with immigration, and you can see that in your bad pension, the lack of affordable housing for your adult children. They said you can solve it if you stop immigration.”

Christina Anderson reported from Stockholm and Steven Erlanger from Brussels.

Les élites doivent écouter les demandes d’identité, de souveraineté et de sécurité des peuples

07/09/2018

JACQUES HUBERT-RODIER | DOMINIQUE SEUX | VIRGINIE ROBERT, Les Echos

En cette fin d’été 2018, le monde vous paraît-il plus dangereux, par exemple, qu’il y a cinq ans ?

Le monde est dangereux sur certains plans et dans certaines régions. Mais il n’y a pas de risque d’enchaînements automatiques, et nous ne sommes pas à la veille d’un affrontement général. Ce sont plutôt nos illusions – occidentales, européennes ou françaises – sur la « communauté internationale » qui s’évanouissent les unes après les autres. A cet égard, Trump est autant un révélateur, une cause, qu’un facteur aggravant. Le plus dangereux c’est le compte à rebours écologique qui n’est pas assez pris au sérieux. Pour le reste, en géopolitique : mer agitée à très agitée partout.

La demande de frontières formulée par les peuples préfigure-t-elle un mouvement de démondialisation ?

Les élites sont bien obligées d’admettre que les peuples occidentaux, classes populaires puis classes moyennes, rejettent une mondialisation trop massive et trop perturbatrice et l’immigration de masse. Mais cela ne veut pas dire pour autant que le monde va se fermer, se « démondialiser ». Personne ne va renoncer à son portable. Je vois plutôt cela, après des excès, comme un balancier qui va se replacer au bon endroit. L’impact social, humain, culturel et identitaire de la baisse des droits de douane et de l’ouverture des marchés et des frontières a été très sous-estimé, c’est donc une correction. Il ne faut pas se faire peur : le monde va rester ouvert, avec plus de régulation, nationale ou internationale, sur les mouvements de personnes.

Que dites-vous à ces élites mondialisatrices, selon votre expression ?

Je n’ai pas grand-chose à dire de plus aux entreprises et à leurs dirigeants, sauf d’accélérer « l’écologisation ». Elles font leur job. En revanche, je dis aux responsables politiques et à tous ceux qui ont accès à la parole publique, qu’il faut entendre les demandes d’identité, de souveraineté et de sécurité des peuples, au lieu de s’en indigner, les canaliser, y répondre.

Quand on voit la façon dont fonctionnent les relations internationales aujourd’hui, notamment avec Donald Trump, le multilatéralisme est-il vraiment mort ?

Il est un idéal pour nous et une pratique en Europe, mais dans le monde d’avant Trump la coopération internationale n’était pas la règle ! Les Américains, y compris Bill Clinton, ont souvent habillé leur imperium derrière une apparence de concertation. Mais au moins elle était là. Le fait que Donald Trump casse ces illusions peut être dévastateur dans la mesure où il fera des émules.

Trump pèse-t-il vraiment sur un sujet comme le réchauffement climatique ?

Il est très nuisible mais il ne peut pas empêcher les Etats-Unis, avec tous leurs chercheurs, leurs villes, leurs entreprises, d’avancer dans la transition écologique. Il met seulement l’administration fédérale hors jeu, pour un temps. De même, s’il y avait une avancée de la coopération internationale pour préserver la biodiversité, les forêts ou les océans, il ne pourrait pas l’empêcher complètement. Mais c’est un handicap.

C’est bien différent sur l’Iran où, grâce à l’omniprésence du dollar, il peut imposer aux entreprises du monde entier un blocus pour provoquer une guerre civile et la chute du régime, comme le veulent Netanyahu et les Saoudiens.

Peut-on encore parler d’hyperpuissance à propos des Etats-Unis ?

A nouveau, oui, et peut-être plus encore qu’avant. J’ai parlé d’hyperpuissance en 1997 parce que le terme classique de superpuissance faisait trop « guerre froide » et qu’il me semblait que c’était la plus grande puissance de tous les temps. Après le 11 Septembre, qui a montré une certaine vulnérabilité américaine, j’ai moins employé ce terme, qui a eu sa vie propre. Mais les Américains conservent des éléments de puissance incomparables : le budget militaire, les Gafa, leur pouvoir judiciaire extraterritorial et abusif auquel nul n’a eu le courage de s’opposer depuis des décennies. L’hyperpuissance du président Clinton était rayonnante, assez séduisante, même si elle était arrogante. Elle associait bien les intérêts américains et une idée générale du monde, comme sous Roosevelt, Truman ou Kennedy. Aujourd’hui, ce n’est plus le cas. Vous avez de nouveau une hyperpuissance, cette fois-ci brutale, agressivement unilatéraliste et, qui plus est, révisionniste de l’ordre « libéral » américain, ce qui est un paradoxe. Emmanuel Macron ne prend pas Trump de front, mais sur chaque point il ne se laisse pas impressionner, tout en assumant qu’il faut maintenir un lien. Il a raison. Mais la question se pose : que faire malgré Trump ? Et que faire contre lui ?

La Chine n’est-elle pas la limite à l’hyperpuissance américaine ?

On verra. Potentiellement, c’est une gigantesque puissance et il n’y a pas de limite apparente à son ascension. Mais dans ma définition de l’hyperpuissance, il y avait aussi la séduction, l’attractivité du mode de vie, cent ans de Hollywood, les universités américaines, avant qu’elles ne soient minées par le politiquement correct, le rêve américain. Les Chinois n’ont pas ça du tout ou pas encore ! Leur réussite est spectaculaire mais leur système n’est pas séduisant. Encore que… En tout cas, pas pour les démocraties établies. Il y a une interrogation sur leur objectif. Les spécialistes de la Chine disent que, méprisant le monde extérieur, ils ne chercheront pas à être prosélytes et ne voudront pas nous convertir à leurs idées, pas de valeurs « chinoises universelles » ! Mais d’un autre côté vous voyez cette puissance économique, multipliée par le nombre, qui permet de neutraliser ou d’influencer déjà 40, 50, 60 voire 70 pays ! De Deng Xiaoping à Xi Jinping, il y a eu des ingénieurs de la décision politique, travaillant dans le temps long, et qui ont bénéficié d’une vraie stabilité.

Depuis les Lumières, les Occidentaux modernes, progressistes, ouverts pensaient être à l’avant-garde de l’humanité. Et voilà que la Chine remet en cause ce rôle, notre supériorité, nos idées ? C’est impensable pour nous ! Il faut pourtant nous préparer à un vaste compromis sur les règles mondiales. Il est urgent de trier dans nos fondamentaux et de voir ce qui est fondamental, et ce qui peut relever d’un compromis avant que les Chinois ne nous mettent devant le fait accompli.

Vous ne voyez pas la Chine comme une puissance expansionniste ?

Pas autant que nous le fûmes, d’Alexandre le Grand à Hitler en passant par Napoléon. La Chine fonctionne plutôt comme un commissariat au plan, qui organiserait, en s’assurant de ses apprivoisements et qui les sécurise, une politique de puissance (route de la soie, etc.) à l’instar de celle de l’Empire britannique et de ses bases. Les Chinois ne sont sans doute pas animés par une volonté hégémoniste allant au-delà de ce qui a été l’empire des Qing. Elle veut surtout maintenir son unité et son intégrité rétablies. Je n’exclus pas complètement un affrontement, un jour, entre les Etats-Unis et la Chine sur la libre circulation en haute mer. Mais si, face à cette gigantesque affirmation chinoise, certaines puissances, comme le Japon, Taïwan, la Corée, l’Inde, l’Australie, l’Europe, les Etats-Unis, s’organisent pour ne pas agir en ordre dispersé afin de faire respecter des règles de base, les Chinois feront attention. Il faudrait pour cela dans les démocraties des dirigeants que les systèmes politiques laisseraient mettre en oeuvre de vraies stratégies !

L’axe indo-pacifique est-il une bonne réponse ?

Oui, si on lui donne un contenu crédible avec les pays concernés. Mais le comportement américain pousse plutôt l’Inde vers la Chine.

Que pensez-vous de la décision du président américain d’imposer des sanctions contre l’Iran mais aussi contre les entreprises faisant du commerce avec ce pays ?

C’est totalement illégal et, pour ceux qui croient encore un peu au droit international, scandaleux. De plus, irresponsable. Pour l’Europe, la conclusion devrait être simple : tout faire pour ne plus dépendre des Etats-Unis, devenus une puissance erratique, même si nous préférons rester ses alliés. Cela est trop dangereux. Il faut reconstruire notre autonomie monétaire (euro, SWIFT).

L’Europe peut-elle devenir une puissance ?

Si l’on met bout à bout le potentiel des Européens sur tous les plans, il est considérable. Emmanuel Macron a fait d’importantes propositions pour une Europe plus forte, mais il faut une volonté explicite et partagée pour les mettre en oeuvre. Créer des mécanismes, des coopérations, des institutions, ne suffit pas. Les Européens ont été autrefois l’incarnation même du jeu des puissances. Après 1945, la construction européenne a intelligemment utilisé la paix imposée par les Soviétiques et les Américains. C’était formidable : il y avait le parapluie américain et le plan Marshall. Mais c’est fini. Pourtant l’idée que l’Europe soit obligée de devenir une puissance dans le monde chaotique d’aujourd’hui terrorise la majorité des Européens…

Est-ce que cela peut changer ?

Oui, si on parvient à sortir les Européens du déni et de leur coma stratégique, en leur démontrant que si l’Europe ne devient pas une puissance (raisonnable et pacifique), avec une autonomie stratégique, elle restera… impuissante, et donc dépendante.

La zone euro n’est-elle pas le bon espace pour faire repartir l’Europe ?

Il faut la renforcer mais, politiquement, cela ne suffit pas. Que l’euro marche bien, et ne soit pas vulnérable à une autre crise monétaire, est un objectif rationnel, important en soi. Mais cela ne répond pas aux attentes des peuples. On ne passe pas directement d’une zone euro, même perfectionnée, à une relance de l’Europe. Relance de quoi d’ailleurs ? Si cela veut dire plus de construction européenne, avec de plus en plus d’intégration comme le veulent les élites intégrationnistes, les peuples ne suivront pas. Sauf si les dirigeants européens arrivent à se mettre tous d’accord sur la maîtrise des flux migratoires, ce qui rendrait les opinions publiques européennes plus réceptives à d’autres progrès en Europe.

Que faut-il faire face à la crise migratoire ?

D’abord sauvegarder le vrai droit d’asile, sans le dévoyer, pour les personnes réellement en danger et, d’autre part, cogérer les flux migratoires économiques avec les pays de départ et de transit, en fonction de nos capacités d’insertion et de nos besoins économiques. On peut imaginer des réunions annuelles avec les pays européens de l’espace Schengen, les pays de départ et ceux de transit, avec une multitude d’accords sur mesure.

Il faut casser le vocabulaire qui est employé à dessein pour tout confondre : demandeurs d’asile et migrants. L’extrême gauche joue la carte migratoire, et de l’islamo-gauchisme. L’extrême droite veut pouvoir dénoncer une invasion générale. Et les ONG ne veulent pas non plus distinguer et parlent de réfugiés à propos de migrants économiques.

Certains pays mettent en avant la montée de l’islamisme pour expliquer la peur des musulmans ? Est-ce que cela peut évoluer ?

Cela diminuera si l’islamisme recule ! Pour le moment ce n’est pas le cas. Il suffit de parler avec des dirigeants musulmans qui sont en lutte chez eux, en première ligne, contre l’islamisme. Je connais beaucoup de musulmans marocains, algériens, tunisiens, mauritaniens, égyptiens, etc. qui disent : « vous êtes trop naïfs. Le voile, c’est organisé, c’est parfois payé. Il faut juste l’interdire. » Ils osent dire que l’islamisme, qui s’est emparé du sunnisme, est un nazisme. Pour moi, il faut une alliance, une coalition mondiale des musulmans modérés et des démocrates.

La France a-t-elle échoué pour trouver une solution à la guerre civile en Syrie ?

Sur la Syrie, les Occidentaux, et nous en particulier, ont échoué. Ses postulats moraux étaient honorables, mais la politique française des dernières années nous a mis hors jeu. En fait, nous n’avons plus de levier, sauf à nous entendre avec les Russes.

Que faire face à la Russie ?

Depuis vingt-cinq ans, les torts ont été partagés entre Occidentaux et Russes. Je ne dis pas que, depuis la fin de l’Union soviétique, elle a été mal traitée, mais elle l’a été de façon idiote. Reconduire sans cesse des sanctions ou haïr Poutine ne constitue pas une stratégie. Il faut en sortir par le haut. Emmanuel Macron a raison de dire qu’il faut réarrimer la Russie à l’Europe, et d’en refaire un partenaire stratégique, même si cela n’est pas facile.

Sweden Was Long Seen as a ‘Moral Superpower.’ That May Be Changing

Steven Erlanger, The New York Times

STOCKHOLM — In a civic center in Rinkeby, a heavily immigrant district of northwest Stockholm, several hundred people gathered recently for a forum on Sweden’s coming election and the future of the country.

The conversation, about the nature of Sweden’s democracy and the importance of voting, was sophisticated and passionate. But it was frustrating for one participant, Ahmed Ali, a Somali immigrant, who thought people were dancing around the main issue.

“The stakes are really high in this election,” he said in an interview. “There are more extremists in the country, and they have more influence. They don’t have a real political agenda. They just hate immigrants. And this xenophobia is happening all over Europe.”

As an angry and divided Sweden prepares to vote on Sunday, the shape of the next Swedish government is utterly unclear, because of the rapid rise of the anti-immigration, anti-Europe Sweden Democrats, a populist nationalist party that is expected to win a fifth of the vote.

“This election is very important to us,” said Kahin Ahmed, 48, who is running for a local seat, but complains that none of the Swedish parties put immigrants or black people high enough on their party lists to get elected in proportionate numbers, even in areas like this one. “There is a racist party moving forward fast, and we have to stop them.”

Sweden, long considered “a moral superpower,” as the political scientist Lars Tragardh put it, has traditionally welcomed immigrants. But that is changing under the pressure of globalization, immigration and anxiety about national and cultural identity. As in Germany and France, parties of the extremes, of the left and especially of the right, are increasing their support at the expense of those that have traditionally dominated.

Sweden “is joining the rest of Europe,” Carl Bildt, a former prime minister from the center-right Moderate Party, said with evident sadness. “And the myth of the Sweden model is melting away.”

The melting was in evidence recently in Sergels Square in central Stockholm, where Martin Westmont, a candidate for the Stockholm regional council, made the Sweden Democrats’ case to the voters.

“We’re the new wave,” he said. The election “will be a revolution.” He predicted that the Social Democrats, the party who built the famous Swedish welfare state, would collapse, “even if not this time,” and “we will become the largest party.” Many voters were still reluctant to tell pollsters that they would vote for the Sweden Democrats, Mr. Westmont suggested.

Populism has shifted the political discourse to the right and raised the temperature, even among the traditionally phlegmatic Swedes. Political support is fragmenting, with the long-dominant Social Democrats heading for their worst showing in a century.

They are losing voters to the Left Party and the Greens, especially after this summer of extensive forest fires, but also some working-class voters to the far-right Sweden Democrats. The Moderates have lost even more to the far right.

The migrant wave of 2015 flowed mostly to Germany and Sweden, regarded as Europe’s most welcoming nations. Germany took in more than one million, while 163,000 arrived in Sweden seeking asylum, a large number in a country of 10.1 million. If the panic in Sweden has been less than in Germany, the political impact has been similar: the rise of a far-right, anti-immigrant, nationalist party — Alternative for Germany in one case, and the Sweden Democrats in the other — that is upending old certainties.

Political elites here as elsewhere “underestimated how much people still live in national democracies,” not some global stew, said Professor Tragardh, who teaches at Ersta Skondal Bracke University College.

As in Germany, stiffer border controls were quickly introduced in Sweden and the numbers of new immigrants fell steeply, to about 23,000 this year. But the political damage had been done, and despite a thriving economy and low unemployment, the Sweden Democrats argue that immigration should stop and that resources should go to refurbishing the welfare state strained by an aging population, gang violence and the challenge of taking on migrants.

Integration of newcomers takes up to seven years, because of tough labor market requirements, insisted upon by Sweden’s trade unions, and the challenges of the country’s language and of its culture, which is more comfortable opening its borders than its homes.

“This election really matters, and it is pretty much up in the air,” said Jonas Hinnfors, a professor of political science at the University of Gothenburg. Welfare, health and taxes are, as ever, top issues, as is climate change, he said, but “to an unprecedented extent, you have immigration and crime, and also unprecedented is the way the Social Democrats are campaigning on these issues and proposing more police and tougher border controls.”

The rise of the Sweden Democrats masks the decline of the Social Democrats, who are synonymous with social democracy in Europe and have come first in nearly every Swedish election since 1917. But while they got over 50 percent of the vote in 1968 and more than 45 percent in 1994, their support has dwindled steadily to about 25 percent, reflecting declines in support for socialist and left-center parties elsewhere in Europe.

If the Sweden Democrats, as expected, get around 20 percent of the vote, that will make it impossible for either the center-left or center-right bloc to form a majority government. The other parties insist that they will not do any deals with the Sweden Democrats, but the question has already cost the Moderates one leader and is bound to come up again in the days after the election, no matter which bloc ends up larger.

The surge of the Sweden Democrats, with their roots in Swedish fascism and neo-Nazism, has astounded many. Under a young leader, Jimmie Akesson, the party has moved to expel its most extreme members and soften its message, symbolized by the switch of its logo from a flaming torch to a floppy version of the blue anemone, one of Sweden’s favorite flowers and a harbinger of spring.

The strategy seems to be working. The party crossed the 4 percent threshold for parliamentary seats in 2010, getting 5.7 percent of the vote; in 2014, it won 12.9 percent. It could now become Sweden’s second-largest party, with all the complications that could bring.

The Sweden Democrats have not abandoned their traditional slogan, “Keep Sweden Swedish,” but have downplayed it in favor of “Security and Tradition.” What they are selling, most people agree, is nostalgia for a mythic Sweden of the 1950s — safe, prosperous and white.

They vow to protect the civil religion of the welfare state and restore the “Folkhemmet,” or the “people’s home,” the idea of the nation as a family where everyone contributes and cares for one another. That concept was created by the Social Democrats, but many consider it threatened by immigration, Islam and crime.

And like other populist parties across Europe, they have been greatly aided by the 2015 migration wave, a rise in gang warfare in the suburbs of big cities and some coordinated and highly visible bouts of car burnings.

Mr. Westmont, 39, the Sweden Democrats’ candidate for the Stockholm regional council, said his experiences growing up were typical of many in his generation who have soured on immigration.

He said he was a youth member of the center-right Moderates, “but they were becoming too liberal for me.” Growing up in a Stockholm suburb, “half the kids” were immigrants. “So I saw the problem from an early age, and I also saw that what the other parties say was not true.”

When he joined the Sweden Democrats in 2010, his parents were so embarrassed that he decided to change his name, he said. “But a lot of Moderates have come to us, and now my father supports the party, and I hope my mother will, too.” Then he smiled and said, “But who knows about mothers?”

Kimia Khodabandeh sees a more sinister side. Age 18 and a first-time voter, she was born in Sweden to Iranian parents who fled the revolution there. “I do feel targeted,” she said. “I was raised Swedish and feel Swedish, but I don’t look Swedish, and they wouldn’t accept us as Swedish.”

“And that’s why I’m concerned,” she continued. “We live in a society where everyone is accepted and helps one another, but we’re heading in the wrong direction. I just don’t understand why some people want to ruin everything.”

In the end, the Social Democrats and the center left may yet cling to power, and the Sweden Democrats may do well but again be kept out of the government. But the question of whether to make some deal with them, as mainstream parties in Finland, Denmark and Norway have done with their far-right rivals, or to continue to isolate them, is unlikely to go away.

“This election is a struggle about values and Swedish identity,” said Ulf Bjereld, a professor of political science at the University of Gothenburg and an active member of the Social Democrats. “The question is how to keep Sweden in the forefront of liberalism and social democracy versus stronger support for the nation state and borders. Who will Sweden be in this struggle? We’re just at the beginning of this debate.”

La France va multiplier par quatre les dons pour l’aide au développement

VIRGINIE ROBERT, Les Echos

L’enveloppe de dons passera à 1,3 milliard d’euros en 2019, alors que les prêts étaient jusque-là privilégiés. Les priorités sont notamment l’Afrique et la formation des jeunes avec le développement d’une approche plus partenariale.

Afin de souligner la priorité que le gouvernement entend désormais porter à l’aide internationale, c’est, symboliquement, depuis le siège de l’Agence française pour le développement à Paris qu’un ministre des Affaires étrangères s’est exprimé pour la première fois, lundi.

Jean-Yves Le Drian a rappelé l’ambition du président Emmanuel Macron d’en faire « une politique d’investissement solidaire » dont les bénéfices pour notre pays « se traduisent en attractivité, influence et sécurité ». Alors que la France est à la traîne par rapport à d’autres puissances plus généreuses (voir graphique), ses moyens devraient atteindre 0,55 % du revenu national brut en 2022 (contre 0,43 % en 2017).

Un besoin de nouvelles méthodes

Cette ambition accrue exige de nouvelles méthodes. « Il faut rétablir les actions bilatérales directes, faire le choix de la contribution vers les pays les plus fragiles en quadruplant l’enveloppe de dons », affirme le chef de la diplomatie française. Ce sont 1,3 milliard d’euros additionnels de dons qui ont été confirmés pour 2019 avec dans le viseur l’éducation, la santé, les fragilités, le climat et les égalités hommes-femmes. « Dans un monde où les logiques de puissances s’expriment de plus en plus fortement, notre aide crédibilise notre parole et notre action économique et diplomatique », assure Jean-Yves Le Drian.

Dans un rapport remis en fin de semaine dernière au Premier ministre Edouard Philippe, le député Hervé Berville (LREM) a souligné « la distorsion grandissante entre les priorités et l’allocation de moyens » de la politique d’aide au développement française. L’Afrique reste ainsi le premier continent bénéficiaire de l’aide française, mais sa part dans l’aide totale nette est passée de 52 % à 41 % en 2016. Le soutien à 19 pays prioritaires oscille seulement entre 10 % et 15 % de l’aide totale nette. Quant à celle réservée aux pays du Sahel, elle est en baisse de 29 % par rapport à l’année précédente, souligne le rapport. Il constate également que ces dernières années, les activités de prêts favorisant les pays les moins risqués ont été privilégiées et que la part de l’aide à l’éducation est très faible.

L’Etat n’a pas su organiser le pilotage politique.

En termes de gouvernance, « l’Etat n’a pas su organiser le pilotage politique ». L’architecture budgétaire est complexe et limite les capacités de contrôle du Parlement. Par rapport aux agences britannique ou suédoise, la France souffre d’un déficit de transparence. « Il faudrait créer une commission indépendante d’évaluation auprès de la Cour des comptes, d’autant que les moyens vont augmenter de six milliards d’euros d’ici à 2022, ce qui est substantiel », explique Hervé Berville. Il milite également pour un développement de la politique partenariale, une action plus affirmée des ambassades ainsi que pour la préparation d’une loi de programmation en 2019, un projet annoncé par le président de la République. « Il faut qu’on sorte de la logique quantitative pour s’intéresser à l’impact, à l’efficacité des programmes et qu’il y ait de la lisibilité dans la durée », estime-t-il.

Une inflexion historique

Le président de l’Agence française pour le développement, Rémi Rioux, parle de mettre en place « un nouveau logiciel » : « La maison double de taille et nous avons maintenant la capacité en dons qui nous manquait ». Concrètement, l’agence de 2.500 personnes devient un groupe qui inclut Proparco (investissements privés), et Expertise France (350 personnes). Un fonds commun avec la Caisse des dépôts doit permettre d’investir dans les infrastructures. Les engagements de l’AFD, qui ont atteint 10,4 milliards d’euros en 2017, vont croître à 14 milliards d’euros en 2019. Trois zones sont ciblées : l’Afrique (dans sa totalité), l’Amérique latine, et les pays d’Outre-mer.

Ces nouveaux moyens et ambitions marquent « une inflexion tout à fait historique », observe Rémi Rioux. A sa charge, désormais, de « susciter, structurer, instruire un nombre beaucoup plus élevé de projets ».

Redressing the European position

04 September 2018

Prince Michael of Liechtenstein, GIS

After two world wars, which were also two European civil wars, the continent lay in ashes and divided. Central Europe was subjected to Soviet rule behind the Iron Curtain, while Western Europe held out under the protection of the United States. France and the United Kingdom officially belonged to the victors, but lost their role as global players and had to dissolve their colonial empires in the 20 years following World War II.

There followed a European miracle, strongly based on the close realignment and newly forged friendship between France and Germany. This led to the European integration process and the European Economic Community (EEC). The resulting single market was a huge success and Europe emerged as a global economic power to be reckoned with. With the collapse of the Soviet Empire, the European Union was further strengthened by the accession of new members from the Baltic region and Central and Southeast Europe.

Over the past 30 years, however, the world’s economic center of gravity started to move from the North Atlantic to the Pacific. While European countries still enjoy a technological lead in a number of sectors, their economies have been hobbled by overregulation, bloated welfare states and protectionist measures (mainly introduced under the pretext of protecting consumers and leveling internal competition through “harmonization”). Europe’s oversized bureaucracies and staggering sovereign debt threaten to strangle its market economies, destroying prosperity, undermining property rights and finally leading to the collapse of unsustainable social security systems.

Besides imperiling their own financial security, European powers also neglected defense – in part out of moral arrogance. They forgot that military strength can be an important factor in global competitiveness. As a result, Europe has remained in security matters an American protectorate, and at best a junior partner of the U.S.

Needed reminder

To stay competitive globally, Europe – though geographically part of Eurasia – needs a close partnership with the U.S. A strong, prosperous and soberly self-confident Europe would be a welcome asset on both sides of the North Atlantic. By leveling the geopolitical playing field, a stronger Europe would also be better positioned to improve relations with the East, especially with Russia.

It needed President Donald Trump’s “direct diplomacy” to issue an overdue wake-up call. Just this past week, French President Emmanuel Macron, German Finance Minister Olaf Scholz and German Foreign Minister Heiko Maas declared that Europe needs to get stronger. Unfortunately, these statements sounded more like expressions of defiance toward Washington than real declarations of intent. Specifics were noticeably lacking.

The solution to Europe’s weakness is not more government programs but letting market forces work

The solution to Europe’s weakness is not more government programs but letting market forces work

It is certainly obvious that Europe’s defense industries need to cooperate more closely to achieve economies of scale. President Macron’s calls for more self-reliance on defense and Mr. Scholz’s advocacy of mergers to improve the efficiency of defense production and procurement make sense. One hopes that implementation will follow, bearing in mind that a planned merger of Airbus and BAE Systems defense units was aborted by European governments just a few years ago.

Heiko Maas is promoting the development of a European financial clearing system independent of SWIFT. Competition in this area would certainly be beneficial. Still, Mr. Maas’s reasoning is faulty, since it starts not with economic efficiency but with a desire to break free from the U.S.

European policymakers are right to worry that their continent lags behind the U.S. and China in digital technology and artificial intelligence. However, the solution is not more government programs but letting market forces work. European overregulation is the stumbling block.

We can be happy if Berlin and Paris work together effectively to promote European interests. However, if this cooperation is driven by opposition to the U.S. and brings more statism, instead of Europe’s defining principles and strengths of diversity, regional competition and subsidiarity, it would be disastrous.

Iran-Amérique : deux stratégies sans issue

Publié

Renaud Girard, Le Figaro

Depuis que la victoire de leur allié baasiste dans la guerre civile syrienne est apparue évidente, les « Gardiens de la Révolution » iraniens n’ont pas manqué de se gargariser de leur stratégie. Quels progrès la République islamique d’Iran n’avait-elle pas accomplis depuis 1988, date à laquelle, épuisée par huit ans de guerre, elle avait dû accepter un armistice sans bénéfice avec son agresseur, l’Irak de Saddam Hussein ! Il y a peu, les Pasdarans se vantaient encore auprès de leurs visiteurs étrangers que la Perse des mollahs avait conquis son accès à la Méditerranée et mis la main sur quatre grandes capitales arabes : Bagdad, Damas, Beyrouth et Sanaa. Ce n’est pas entièrement faux et l’axe chiite est une réalité au Moyen-Orient.

Le militaire qui monte à Téhéran, le général Qasem Soleimani, patron de la Force d’intervention Al-Qods, le fer de lance à l’étranger du Corps de Gardiens de la Révolution, a indéniablement accru l’influence régionale de son pays. Tel un bon judoka, l’Iran a su depuis trente ans retourner en sa faveur les attaques, directes ou indirectes, déclenchées contre lui ou contre ses alliés.

Sur quatre crises, on peut dresser des constats qui se terminent à l’avantage de l’Iran. Lorsque les Américains se retirent militairement en août 2010 de l’Irak, qu’ils avaient envahi en mars 2003, c’est pour – bien involontairement – le donner sur un plateau d’argent aux forces politiques chiites pro-iraniennes.

Au début de l’été 2015, personne n’aurait parié un kopeck sur le sort du régime laïc de Bachar al-Assad en Syrie, qui a réuni contre lui la Turquie, l’Arabie saoudite, le Qatar, les Etats-Unis, la France et les djihadistes sunnites de l’ensemble du monde arabo-musulman. Damas est à deux doigts de tomber. L’Iran est très préoccupé par son vieil allié syrien, le seul qu’il ait eu lors de la guerre du Golfe de 1980-1988. Le général Soleimani fait alors le voyage de Moscou, pour convaincre Vladimir Poutine d’envoyer un corps expéditionnaire russe en Syrie. C’est chose faite en septembre 2015 et le régime est sauvé.

Au Liban, le Hezbollah sort politiquement victorieux des 33 jours de guerre qu’il a fait à Israël pendant l’été 2006. La milice chiite libanaise (fondée par les Pasdarans en 1982) n’a bien sûr pas battu militairement l’Etat hébreu. Mais comme elle a résisté à l’anéantissement que lui promettaient les dirigeants israéliens – une première chez les arabes -, elle peut proclamer sa « divine victoire ». En mai 2008, après une démonstration de force dans les quartiers sunnites de Beyrouth, le Hezbollah va obtenir ce qu’il a toujours recherché : un droit de veto sur toutes les décisions stratégiques du gouvernement libanais.

Au Yémen, la coalition arabe dirigée par l’Arabie saoudite, principal rival régional de l’Iran, piétine ; elle ne parvient pas à reprendre la capitale aux montagnards Houthis, que Téhéran soutient à très peu de frais.

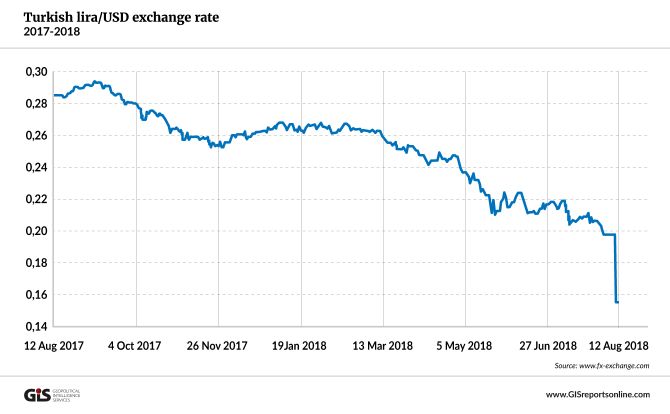

Mais à quoi servent à l’Iran ses succès militaires avérés ? En quoi lui profite son « accès à la Méditerranée » ? Quel est le bilan coûts-avantages de la constitution du fameux axe chiite ? Désormais soumis à un terrible régime de sanctions américaines, l’économie iranienne s’effondre. La population se lasse des aventures extérieures de ses dirigeants. Au demeurant, les prises de guerre ne sont pas si belles : le territoire syrien est ravagé ; la colère populaire gronde dans le port irakien de Bassora, toujours privé d’électricité et d’eau potable ; encouragé par les Emiratis, le Sud du Yémen se prépare à faire sécession ; redevenu une place financière, le Liban applique à la lettre les diktats du Trésor américain. A quoi sert de hurler contre Israël, alors même que les nations arabes se rapprochent de l’Etat juif ? A quoi sert une puissance qui n’apporte pas la prospérité à son peuple ? La stratégie iranienne apparaît de plus en plus sans issue.

Invoquant leur dignité bafouée, les dirigeants iraniens ont eu tort de refuser l’offre de dialogue de Donald Trump. Mais, de son côté, la Maison Blanche aurait tort de suivre les recommandations extrêmes de John Bolton (Conseiller à la Sécurité nationale), qui veut asphyxier les Iraniens, pour les forcer à changer de régime. Cela ne se produira pas. Le résultat risque d’être l’inverse : l’éviction du président modéré Rohani, et le couronnement du général Soleimani.

L’Iran, dont les élites estudiantines et entrepreneuriales sont prooccidentales, se transformera par la réforme progressive, mais pas par une nouvelle révolution ou quelque violent changement de régime. Washington semble ne pas l’avoir compris.

L’Iran et l’Amérique entretiennent l’un avec l’autre des stratégies sans issue. Tant que se poursuivront ces haines recuites, le Grand Moyen-Orient ne connaîtra ni la stabilité politique, ni le retour de la confiance économique, pourtant indispensables au développement harmonieux de la région.

The Two Sides of American Exceptionalism

Any post-Trump US president will confront a fundamental question. Can the US promote democratic values without military intervention and crusades, and at the same time take a non-hegemonic lead in establishing and maintaining the institutions needed for a world of interdependence?

Renaud Girard: “L’immigration de masse est un scénario perdant-perdant”

FIGAROVOX/GRAND ENTRETIEN – Alors que la question de la crise migratoire occupe l’espace médiatique et le débat public, Renaud Girard analyse les conséquences de l’immigration massive sur les pays d’Europe comme ceux d’Afrique.

Renaud GIRARD.- Il est évident que les pays européens n’ont plus les moyens économiques, sociaux et politiques d’accueillir toute la misère du monde.

Prenons le cas de la France. Si nous regardons la question de l’emploi, nous voyons que, toutes catégories confondues, le nombre d’inscrits à Pôle Emploi s’élève à 6 255 800 personnes. Une économie en sous-emploi n’est pas en mesure d’absorber des millions de migrants. N’oublions pas que les vagues d’immigration des années 50-60 arrivaient dans une France en plein boom économique et où le chômage n’existait pas. Ce n’est plus le cas aujourd’hui.

Mais surtout, l’immigration de masse pose un problème identitaire et culturel. L’Homme n’est pas qu’un homo economicus désincarné, sans histoire ni racines ; il est avant tout un être de culture. La culture européenne -fille de l’Antiquité, du judéo-christianisme et des Lumières- risque d’être submergée par des populations dont le mode de vie est incompatible avec le mode de vie européen et dont la présence massive sur notre sol ne peut aboutir qu’à des tensions. L’immigration de masse sape la cohérence, l’unité et la solidarité des sociétés occidentales. Au lieu d’une société unie, l’immigration fragmente le corps social en une multitude de communautés indifférentes, voire hostiles, les unes aux autres. Certains membres des minorités (pas tous heureusement!) refusent de s’intégrer et basculent dans la délinquance, leur haine de notre pays pouvant aller jusqu’au terrorisme.

Cette crise migratoire peut-elle avoir de graves conséquences politiques?

Cette crise identitaire risque bien de se transformer en crise politique.

D’une part, on constate partout en Europe l’inquiètante progression des mouvements extrêmistes – en Allemagne, en France, en Italie, en Grèce…. Ce phénomène politique est une conséquence directe de l’immigration. Dans les années 70, le Front National était un obscur groupuscule de nostalgiques de l’Algérie française. Sa percée électorale à partir du début des années 80 s’explique par l’immigration massive et les craintes qu’elle suscite. Il y a quelque chose de paradoxal chez les bonnes âmes bien pensantes qui à la fois fustigent les partis extrêmistes et soutiennent l’immigration. Cela est incohérent. En effet, c’est l’immigration qui nourrit les partis extrêmistes et risque un jour de les amener au pouvoir.

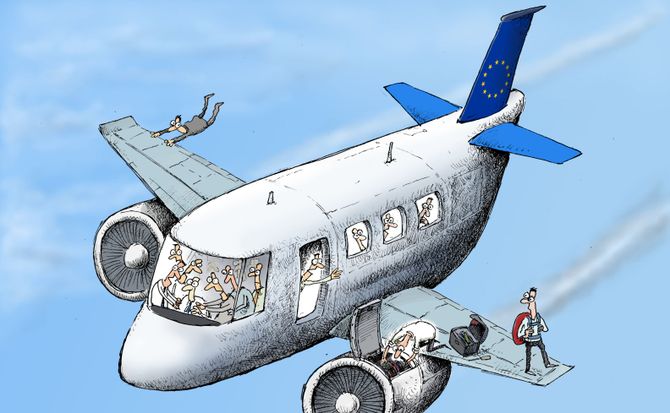

D’autre part, la crise migratoire risque de détruire l’Union européenne. 73 % des Européens considèrent que l’UE ne les protège pas. Partout, l’immigration favorise la montée des populismes. Au Royaume-Uni, le vote en faveur du Brexit s’explique en grande partie par le rejet de l’immigration. Les pays d’Europe centrale refusent tout diktat de Berlin leur enjoignant d’accepter des migrants sur son sol. L’Italie n’en peut plus, qui a vu plus de 70 000 migrants illégaux débarquer sur ses côtes depuis 2013.

Sa générosité a des limites. Son nouveau ministre de l’Intérieur a prévenu que l’Europe institutionnelle jouait son existence même sur la question migratoire. Venant de la part d’un pays fondateur du Marché commun, c’est un message qu’il faut prendre au sérieux.

Mais alors comment s’y prendre concrètement pour régler le problème migratoire?

Nous devons réduire massivement l’immigration.

Pour atteindre cet objectif, nous devons reprendre le contrôle de nos frontières, suspendre le regroupement familial, lutter drastiquement contre l’immigration clandestine, rétablir la double peine. Toute personne étrangère qui commet un acte de violence ou connaît un début de criminalisation doit être aussitôt expulsée.

Pour l’immigration illégale, terrorisons les passeurs en démantelant leurs réseaux, en menant des actions de guerre contre eux et en leur infligeant des peines drastiques lorsque nous les capturons. Montrons bien aux migrants que leur démarche est vaine en leur refusant systématiquement tout titre de séjour et toute aide sociale. Cela nous permettra d’arrêter l’appel d’air européen. Et faisons le savoir dans leurs pays pour décourager les tentatives.

À cela doit s’ajouter, dans la plus pure tradition gaulliste, une politique humaniste, solidaire et active de codéveloppement avec les pays pauvres afin de leur permettre un développement économique, respectueux de l’environnement, créateur d’emplois et réducteur d’inégalités, de façon à réduire la tentation du départ.

Nous devons aussi cesser les aventures néocoloniales dans les pays du Moyen-Orient. Sans la catastrophique Guerre en Irak en 2003, il n’y aurait pas eu Daech ni les hordes de migrants syriens et irakiens de l’été 2015. En Libye, Kadhafi n’était peut-être pas très sympathique, mais il nous rendait service en servant de verrou face à l’immigration.

De manière plus précise, quelles sont les priorités pour faire face à l’afflux de migrants africains traversant la Méditerranée depuis les côtes libyennes?

Les nouvelles priorités sont limpides: reconstruire un État en Libye et aider ses forces armées à combattre les trafiquants d’êtres humains et à sécuriser ses frontières méridionales dans le Fezzan ; déployer, aux côtés de la marine nationale de Libye, et dans ses eaux territoriales, des navires de surveillance européens capables de ramener les naufragés ou les dinghies surchargés d’êtres humains vers leur rivage d’origine. Le littoral libyen était naguère équipé de radars de surveillance que l’Union européenne avait financés. Ils furent détruits par des frappes franco-britanniques durant la guerre de 2011 contre le régime de Kadhafi. La coopération militaire, policière, humanitaire, avec les autres États d’Afrique du nord doit évidemment se poursuivre.

En Afrique noire, il faut en même temps accroître l’aide économique de l’Union européenne et la soumettre à condition. Tout d’abord, il faut être sûr que cette aide bénéficie bien aux populations et ne soit pas détournée par des administrations ou des gouvernements corrompus. Ensuite, il faut lier cette aide, c’est-à-dire la conditionner, à la mise en place d’un planning familial efficace. Soixante ans de coopération technique européenne avec l’Afrique n’ont pas réussi à y greffer le concept pourtant élémentaire de planning familial.

«Si nous ne réduisons pas la taille de nos familles, notre pays continuera à souffrir de la pauvreté parce que les ressources disponibles ne pourront plus couvrir nos besoins», a reconnu Jonathan Goodluck, ancien président (2010-2015) du Nigeria. C’est de ce pays aux richesses naturelles fabuleuses, mais mal gérées et mal partagées depuis l’indépendance en 1960, que proviennent aujourd’hui le plus grand nombre de ces jeunes immigrants illégaux qui essaient par tous les moyens d’atteindre les rivages du nord de la Méditerranée. Le Nigeria comptait 34 millions d’habitants en 1960. Il en compte aujourd’hui presque 200 millions. Enfin, il faut orienter cette aide vers un développement de projets agricoles et énergétiques concrets, capables de nourrir et retenir chez elles les familles africaines. Le but de cette aide n’est pas d’industrialiser l’Afrique (ce qui ne ferait qu’augmenter les déséquilibres et donc accroître l’immigration) mais de développer des projets locaux, respectueux des sociétés traditionnelles (microcrédit, circuits courts, agriculture vivrière, biologique et équitable…).

Vous dites que l’immigration de masse est un «scénario perdant-perdant». Pouvez-nous nous expliquer ce concept?

C’est un jeu auquel tout le monde perd. Le trafic d’êtres humains sur lequel repose aujourd’hui l’immigration africaine est profondément délétère à la fois pour les États africains et pour les États européens.

Comme je l’ai dit, l’Europe y perd sur les plans économique, culturel, sécuritaire et identitaire.

L’Afrique y perd, car elle se vide de sa sève. L’émigration prive l’Afrique d’une jeunesse intelligente, entreprenante et débrouillarde. Car les 3000 euros qu’il faut payer pour le trajet y représentent une somme considérable à rassembler. Dans les pays du Continent noir, c’est un beau capital de départ pour créer une affaire, pour creuser un puits dans un village, ou pour monter une installation photovoltaïque. Bien souvent, les migrants ne sont pas les plus pauvres mais des membres de la petite classe moyenne. Dans les pays de transition comme le Niger, le trafic attire des jeunes pressés de faire fortune, les éloignant de l’élevage, de l’agriculture, de l’artisanat. Il n’est pas sain que les villages africains vivent dans l’attente des mandats qu’envoient ou qu’enverront les migrants une fois arrivés en Europe, plutôt que de chercher à se développer par eux-mêmes. Il est vital que les aides financières de l’Union européenne pour le Sahel et l’Afrique centrale aillent dans des actions qui combattent l’économie de trafic, mais aussi dans des projets agricoles ou énergétiques capables de fixer les populations sur leurs terres ancestrales.

Enfin, les migrants eux-mêmes sont perdants. Ils déboursent de l’argent pour voir leurs rêves déçus. Ils attendaient le Paradis et se retrouvent perdus dans des pays où leur situation est très difficile.

Les seuls gagnants, ce sont les passeurs.

Justement, parmi les acteurs centraux de cette immigration illégale, il y a les passeurs…

Les passeurs sont des bandes mafieuses sans scrupule, qui promettent monts et merveilles aux migrants avant de se livrer aux pires exactions sur eux (escroquerie, racket, violences, viols, abandon en pleine mer…).

Aujourd’hui, ce sont les mêmes réseaux mafieux qui procèdent indifféremment au trafic d’armes (destinées aux djihadistes), à l’acheminement de la drogue vers l’Europe, au trafic des êtres humains.

Les passeurs – ces nouveaux Barbaresques – ont une méthode éprouvée. Ils entassent les candidats aux voyages dans des canots pneumatiques de fortune ; ils les poussent jusqu’aux eaux internationales à 12 nautiques du rivage libyen ; ensuite ils émettent un SOS ou appellent un centre de secours italien pour indiquer qu’un naufrage est imminent ; puis ils s’en retournent dans leurs repaires, abandonnant à leur sort leurs malheureux passagers, souvent sans eau douce ni nourriture. Le reste du voyage ne coûte plus rien aux passeurs, puisqu’il est pris en charge par les navires des marines ou des ONG européennes. Pourquoi ces derniers ne ramènent pas simplement les naufragés vers les ports les plus proches du littoral libyen? Parce qu’ils considèrent qu’il s’agirait d’un refoulement contraire au droit humanitaire international. Les nouveaux Barbaresques le savent bien, qui sont passés maîtres dans l’art d’exploiter le vieux sentiment de charité chrétienne de cette Europe si riche, si bien organisée, si sociale.

Quel regard portez-vous sur les ONG?

Sans le vouloir, certaines ONG participent, de manière gratuite, à un immense trafic, qui a dépassé depuis longtemps en chiffre d’affaires le trafic de stupéfiants.

Les ONG détournent le droit d’asile. Le meilleur moyen de s’installer en Europe pour un immigré illégal est de se faire passer pour un réfugié politique et d’invoquer le droit d’asile. Celui-ci a été forgé par les Français de 1789 pour accueillir les étrangers persécutés dans leurs pays pour avoir défendu les idéaux de la Révolution française. Le droit d’asile ne peut concerner que des individus, et non pas des groupes. Il ne peut s’appliquer qu’à des gens engagés politiquement et visés personnellement à cause de leur engagement. Il ne saurait valoir pour des gens qui fuient la misère ou même la guerre. Or, on assiste aujourd’hui à un détournement massif du droit d’asile, car l’écrasante majorité des réfugiés sont des réfugiés économiques. Une fois qu’il a mis le pied sur le sol européen, le migrant sait qu’il pourra y rester à loisir, car les reconduites forcées vers l’Afrique sont statistiquement rares.

Pour comprendre le problème des ONG, il faut revenir à la distinction du sociologue allemand Max Weber entre éthique de conviction et éthique de responsabilité. Ceux qui agissent selon une éthique de conviction sont certains d’eux-mêmes et agissent doctrinalement. Ils suivent des principes sans regarder les conséquences de leurs actes. Au contraire, l’éthique de responsabilité repose sur le réalisme, le pragmatisme et l’acceptation de répondre aux conséquences de ses actes.

Aujourd’hui, les ONG qui viennent au secours des migrants sont dans l’éthique de conviction. Elles déposent les migrants sur les côtes italiennes et s’offrent un frisson narcissique en jouant au sauveteur. Mais après elles n’assurent pas la suite du service: elles ne se demandent pas ce que devient le migrant en question ni quelles sont les conséquences politiques et culturelles de ces migrations sur l’Europe. Pour sortir de la facilité, les membres des ONG devraient héberger eux-mêmes les migrants, les éduquer, leur trouver du travail. Peut-être auraient-ils une autre attitude.

Bien sûr, la compassion et la bienveillance sont des valeurs cardinales. Il n’est pas envisageable de laisser des gens se noyer en mer quand un navire les croise. Il faut les sauver. Mais il faut ensuite les redéposer sur les côtes libyennes, leur point de départ. Puisque de toute façon, leur présence en Europe est illégale.

Pourquoi les politiques migratoires européennes sont-elles selon vous un «déni de démocratie»?

L’arrivée incontrôlée et en masse de migrants peu au fait de la culture européenne déstabilise profondément les États de l’UE, comme on l’a vu avec le vote référendaire britannique et le vote législatif italien. Dans les années cinquante et soixante, les peuples européens se sont exprimés par les urnes pour accepter les indépendances des ex-colonies. En revanche on ne les a jamais consultés démocratiquement sur l’immigration, qui est le phénomène social le plus important qu’ils aient connu depuis la seconde guerre mondiale.

En France, la décision d’État la plus importante du dernier demi-siècle porte aussi sur la question migratoire. C’est le regroupement familial. Il a changé le visage de la société française. Il est fascinant qu’une décision aussi cruciale ait été prise sans le moindre débat démocratique préalable. Il s’agit d’un décret simple d’avril 1976, signé par le Premier ministre Jacques Chirac et contresigné par Paul Dijoud. Ce ne fut donc ni un sujet de débat, ni l’objet d’un référendum, ni une loi discutée par des représentants élus, ni même un décret discuté en Conseil des Ministres, mais un décret simple comme le Premier Ministre en prend chaque jour sur des sujets anodins. Cette mesure provoqua immédiatement un afflux très important de jeunes personnes en provenance de nos anciennes colonies d’Afrique du nord.

Consultés par référendum par le général de Gaulle – qui ne voulait pas d’un «Colombey-les-deux-Mosquées» -, les Français ont accepté, en 1962, de se séparer de leurs départements d’Algérie, où une insurrection arabe brandissant le drapeau de l’islam avait surgi huit ans auparavant. Cinquante-six ans plus tard, ils voient les titres inquiets de leurs journaux: «450 islamistes vont être libérés de prison!». Ils s’aperçoivent alors qu’on leur a imposé en France une société multiculturelle, sans qu’ils l’aient réellement choisie. Jamais les Français ne furent interrogés sur l’immigration de masse, le multiculturalisme et le regroupement familial.

De même, Angela Merkel (qui avait pourtant reconnu l’échec du multiculturalisme allemand en 2010) n’a pas jugé bon de consulter son peuple lorsqu’elle déclara unilatéralement que l’Allemagne accueillerait 800 000 migrants. Pourtant il s’agit là de choses fondamentales qui concernent à la fois la vie quotidienne des citoyens et l’identité profonde du pays.

La démocratie ne consiste-t-elle pas à interroger les populations sur les choses les plus importantes? La démocratie ne sert-elle pas à ce que les peuples puissent décider librement de leurs destins? On peut fort bien soutenir que le brassage culturel enrichit les sociétés modernes. Mais, dans une démocratie qui fonctionne, le minimum est que la population soit consultée sur l’ampleur du multiculturalisme qu’elle aura ensuite à gérer sur le long terme.

Washington consolide l’axe russo-chinois

27 août 2018

Renaud Girard, Le Figaro

Lorsque Henry Kissinger pilotait la politique extérieure américaine dans la première moitié de la décennie 1970-1979, il avait inventé le concept de « triangle stratégique ». Il fallait que l’Amérique s’arrange toujours à être plus proche à la fois de la Russie et de la Chine, que ces deux nations orientales pouvaient l’être entre elles. Au cours de l’année 1972, il parvint à ce que le président Richard Nixon se déplace en février à Pékin – pour y établir des relations diplomatiques -, et en mai à Moscou – pour y signer le premier traité de limitation des armes nucléaires stratégiques.

L’Amérique de Donald Trump suit un chemin opposé. Il ne se passe pas une semaine sans qu’on se demande comment Washington va parvenir à détériorer encore sa relation avec Moscou et avec Pékin. Le lundi 27 août 2018, de nouvelles sanctions américaines sont entrées en vigueur contre la Russie. Ces mesures, s’appuyant sur une législation de bannissement des armes chimiques, consistent à interdire l’exportation vers la Russie de produits américains jugés sensibles pour la sécurité nationale. L’idée est de punir le régime de Moscou d’avoir utilisé, en mars 2018, un agent neurotoxique à Salisbury (Angleterre) contre le transfuge Skripal, agent du GRU (service de renseignement militaire russe) passé naguère au service de Sa Majesté britannique. Le porte-parole du Kremlin a rejeté vigoureusement toute implication de l’Etat russe dans cet empoisonnement. Estimant « illégales » de telles sanctions, il a accusé les Etats-Unis de « sciemment choisir le chemin de la confrontation » avec la Russie. Devant le président finlandais qu’il recevait à Sotchi, Vladimir Poutine a jugé ces sanctions « très contre-productives et dénuées de sens », appelant à une « prise de conscience » de l’establishment américain.

En même temps, Washington poursuit son bras de fer commercial avec la Chine. Jeudi 23 août 2018, les Etats-Unis ont imposé des droits de douane de 25% sur 50 milliards de dollars d’importations en provenance de Chine. Le président Trump estime que les Chinois traînent les pieds pour mettre fin à leur pillage de la technologie américaine, et pour réduire leur gigantesque excédent commercial (500 milliards d’exportations de la Chine vers les Etats-Unis, contre 125 milliards de dollars dans l’autre sens). Les autorités de Pékin ont qualifié d’illégales ces mesures tarifaires et ont déposé une plainte auprès de l’Organisation mondiale du Commerce (OMC). Comme le président Xi Jinping ne peut se permettre de perdre la face, la Chine va prendre des mesures de représailles, et personne ne voit de fin prochaine à cette spirale. Elle peut même prendre à tout moment une vilaine tournure stratégique, par instrumentalisation du dossier nord-coréen. Déjà, Washington accuse Pékin de laxisme dans l’application des sanctions de l’Onu contre la Corée du Nord nucléarisé.

Sur le fond, les Américains n’ont pas entièrement tort lorsqu’ils accusent la Russie de vouloir retrouver par tous les moyens une « sphère d’influence » – prévue dans aucun traité – sur l’ensemble du territoire de l’ex Union soviétique, ou lorsqu’ils reprochent à la Chine de ne pas respecter l’esprit des accords de l’OMC. Mais ils le font avec une telle maladresse qu’ils risquent d’aboutir à un résultat opposé. Sans le vouloir, par sa pratique d’une diplomatie punitive, l’Amérique ne cesse de consolider contre elle un axe russo-chinois.

Dans la première quinzaine du mois de septembre, la Russie va procéder, en Sibérie, aux plus importantes manœuvres militaires qu’on ait connues depuis 1981. Invitée, la Chine a décidé d’y envoyer un détachement de 900 blindés de toutes sortes et de 3500 hommes. Les deux puissances sont en train de redevenir alliées, comme elles l’étaient dans la décennie 1950-1959. Elles ne supportent pas la prétention des Américains à imposer leur droit sur l’ensemble du globe, tout en malmenant de manière unilatérale la Charte des Nations unies. Elles songent à remettre en cause la suprématie du dollar comme monnaie mondiale de réserve et d’échange. Elles soutiennent l’Iran, sévèrement boycotté par Washington.

Il y a trente ans, les stratèges américains considéraient qu’il fallait se montrer ouverts face à la Chine. Inquiets face à l’expansionnisme maritime chinois et face à la montée en puissance de l’ « Armée populaire de libération », ils prônent aujourd’hui une stratégie de « containment ». Les Russes ne les aideront certainement pas.

Dans sa guerre commerciale avec la Chine, Trump a été maladroit deux fois : il a renié le traité transpacifique qui formait un bloc asiatique efficace face à elle ; il n’a pas su s’allier avec l’Union européenne.

La rivalité sino-américaine est la grande affaire stratégique du XXIème siècle. Mais l’Amérique n’a toujours pas compris qu’elle n’a aucun intérêt aujourd’hui à pousser les Russes dans les bras des Chinois.

Europe’s Dog Days of Summer

Addressing the challenges Europe faces will demand the sustained implementation of smart, forward-looking policies, carried out by the EU’s core institutions. Yet, following a five-year period of unprecedented political fragmentation in the EU, the outlook for the functionality of these institutions appears grim.

MADRID – August is always a good time for taking stock. Between the rush of summer activity and the beginning of the new “school year,” this month’s lull offers a moment for reflection on where matters in Europe stand – and where they are headed. The European Union, and its headquarters in Brussels, is no exception, particularly ahead of a year of transitions. But amid speculation over the coming challenges and changes, the one new appointment that could make or break the EU over the next five years, that of the European Council president, has been completely overlooked.

Europe’s attention has been trained on three issues that pose a clear and imminent threat: Brexit, migration, and rising nationalism, which in countries like Poland is fueling growing resistance to the EU and the rule of law. How these issues are handled will affect the future and functionality of the EU. This is particularly true for Brexit, which – despite the gloom and doom hovering over the negotiations – seems likely to result in the two sides buying time with a transitional agreement that will create space for a permanent arrangement.

In any case, addressing these and other challenges will demand the sustained implementation of smart, forward-looking policies, carried out by the EU’s core institutions: the European Parliament, Commission, and Council. Yet, following a five-year period of unprecedented political fragmentation in the EU, the outlook for the functionality of these institutions appears grim.

Let’s start with the European Parliament, which in the early days of European integration was marginalized, powerless, and overlooked – a place for has-beens and never-weres. But over the last decade and a half, the Parliament has worked hard to secure more power, elbowing its way into the formal legislative process, securing for itself oversight authority, and even inserting itself into the process of selecting the European Commission president.

But the way the European Parliament wields its newfound power may be about to change, following the next EU-wide election in June 2019. So far, traditional center-right and center-left pro-European parties have dominated it, with more extreme parties never really pulling the institution far from its center of gravity.

Since the last European elections, however, the continent’s politics have undergone a profound transformation, with 41 new parties winning seats in national parliaments since 2014. The European Parliament is almost certain to become significantly more fragmented – a consequential development, given the power it has recently accrued.

The same fragmentation is set also to weaken the European Commission, with commissioners from at least four countries – the Czech Republic, Greece, Italy, and Poland – set to be appointed within a year by Euroskeptic governing parties. Speculation about who will succeed Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker has already begun; ultimately, however, the answer will probably make little difference.

Juncker’s feckless “last-chance commission” will be succeeded by a “next-chance commission” – one that may fall even more short of the mark. After all, since the global financial crisis erupted in 2008, it has become starkly apparent that the real power in the EU lies not in the transnational precincts of the Commission, but in the intergovernmental corridors of the European Council. This trend is highlighted by the German government’s reported desire to put a German – perhaps economy minister Peter Altmaier or defense minister Ursula von der Leyen – at the head of the Commission, in order to bring the institution closer to Berlin.

When it comes to the Council, the outlook is also bleak. The national leaders who oversee it lack the vision, commitment, or strength to set the direction for the European project. German Chancellor Angela Merkel, Europe’s leading power for the last ten years, has been weakened. French President Emmanuel Macron has lost momentum. The United Kingdom is on its way out. Italy, Poland, and Hungary are openly skeptical of Europe. Spain has an unelected minority government, and the Netherlands is paralyzed by right-wing opposition.

In short, none of the EU’s institutions seems to be in a position to respond to the serious challenges they face. This brings us to one of the most recent additions to the EU structure, created by the Treaty of Lisbon: the European Council president.

The importance of the European Council president is often overlooked. But, as the first holder of the position, Herman Van Rompuy, demonstrated when he held the post, it can be integral to progress. During the euro crisis, Van Rompuy, working largely behind the scenes, marshaled support for badly needed measures among the member states and the three cornerstone EU institutions.

Not everyone can carry the weight of the position. An effective European Council president must have a temperament that enables him or her to move a diverse group of powerful people toward mutually beneficial outcomes, all without taking the spotlight. Van Rompuy’s higher-profile successor, Donald Tusk, is a good counter-example.

The right European Council president can act as a rudder for the entire European project. But the wrong one will leave the EU directionless at a moment when united action is urgently needed. Preventing that outcome should be a top priority for Europe’s leaders.

Shortsightedness and stubbornness are holding Europe back

28 August 2018

Prince Michael of Liechtenstein, GIS

Europe, especially Western Europe, has been a lucky part of the world since World War II. Wise statesmanship led it to reconciliation and economic integration.

In old Greek dramas, when humans have too much success the gods get jealous and blindfold them. One could be forgiven for thinking this has happened in Europe, considering its politics. There are a few examples that warrant mention.

The one most talked about is Brexit. Under the pretext of ever closer integration, the European Union proceeded toward centralization and excessive harmonization. Some EU members were not happy with such initiatives, especially the United Kingdom. Former Prime Minister Cameron frequently and publicly criticized Brussels. To win parliamentary elections in 2015, Mr. Cameron shortsightedly promised a vote on further EU membership in 2016, though he was convinced that the UK should stay a member. Mr. Cameron won, and the referendum was scheduled for June 2016. There was a widespread belief that the British electorate would decide to remain within the bloc.

Blackmailing the electorate

During the preparation for the vote, blunders were committed on all sides. After all his previous criticism of the EU, Prime Minister Cameron’s campaign for the UK continue as a member was unconvincing. The British people were not well-informed, while the main arguments for remaining in the EU were threats of punishment from the bloc. Brussels and many of the continental European governments trumpeted such threats. Former United States President Barack Obama joined the concert. He warned that if Brexit occurred, the U.S. would put negotiating a trade deal with the UK at the bottom of the stack of trade agreements it was working on. All these so-called “professional politicians” ignored that electorates do not respond well to such threats and consider them blackmail.

A ‘hard Brexit’ may become a reality due to this lack of a practical strategy

A ‘hard Brexit’ may become a reality due to this lack of a practical strategy

German Chancellor Angela Merkel’s “Willkommenskultur” (culture of welcome) to refugees – which had flimsy legal foundations and was not coordinated internally or with European partners – was also rather unhelpful.

To general shock around the world, the Brexit side won. Some 52 percent of British voters opted to leave the EU. Unfortunately, Brussels responded with a stubborn pronouncement that an “ever closer union” remained its goal. Both parties – but especially the EU – have, to everybody’s detriment, remained wedded to unrealistic principles instead of being pragmatic. A “hard Brexit” may become a reality due to this lack of a practical strategy.

Sovereign debt

One of the biggest threats is sovereign debt. This issue can only be solved by reducing public spending on consumption (this does not include necessary infrastructure investments). A main unresolved topic is the “implicit pension debt,” or IPD. By this, we understand pension obligations that governments, including regional and local authorities, have incurred toward current and future pensioners. These obligations are not included in the national accounts.