Postwar relations between China and Japan have seen a number of epoch-making occasions, and one of the most important events in recent years was the November 2014 summit meeting between then-Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and Chinese President Xi Jinping.

The meeting became an opportunity for the two countries, which had been experiencing increased friction and tensions over the Senkaku Islands, to ease and stabilize strained relations.

Prior to the Abe-Xi meeting on Nov. 10, 2014, the governments of the two countries released a four-point statement titled “Regarding Discussions toward Improving Japan-China Relations.”

The statement said, “Both sides confirmed that they would observe the principles and spirit of the four basic documents between Japan and China and that they would continue to develop a mutually beneficial relationship based on common strategic interests.”

The four documents are the joint communique released on Sept. 29, 1972; the peace and friendship treaty issued on Aug. 12, 1978; the joint declaration released on Nov. 26, 1998; and the joint statement issued on May 7, 2008.

We can say that both countries share the common view that the documents serve as the basis of today’s China-Japan relations, although there are difficulties and uncertainties existing between them.

Nevertheless, Japan’s China policy fluctuated largely in the 30 years after the end of the Cold War and as a result it has been difficult for Tokyo to plan long-term policies.

But what constitutes a favorable Japan-China relationship from Tokyo’s viewpoint, and what kind of approach is Japan trying to take?

Several other questions also arise when trying to understand the ties between Beijing and Tokyo.

How should Japan regard China’s economic growth?

How does establishing favorable China-Japan ties comply with the U.S.-Japan alliance?

And how will Japan achieve a balance between the national interests of maintaining economic ties with China and the threats posed by Beijing from national security perspectives?

Japan’s basic stance on China seems to have been not having a China strategy.

In other words, it is difficult to show any documents that clearly describe Japan’s strategy on China.

Complexity

So why did Japan lack a China strategy until now? There are three main reasons.

First is the complexity of Japan’s relationship with Taiwan.

The postwar China-Japan relationship had been based on ties with the “two Chinas” — the relations with Taiwan defined by the peace treaty signed by Tokyo and Taipei on April 28, 1952, the same day that the San Francisco Peace Treaty came into force, and relations with China defined by the 1972 China-Japan joint communique and the 1978 peace and friendship treaty signed by Beijing and Tokyo.

And the outline of these relations was not built by Japan on its own initiative but rather was largely determined by the U.S.-China relationship of the times.

At the time of signing of the San Francisco Peace Treaty in September 1951, how to handle the two Chinas had been a difficult diplomatic issue between the United States and the United Kingdom, as well as between the U.S. and Japan. But the policy had been established for Japan to choose to side with the government in Taiwan.

After Japan normalized diplomatic ties with China in 1972, it became difficult for Tokyo to come up with a proactive strategy that would respond to the sensitive question of how to balance between China and Taiwan while respecting Beijing’s “one China” position.

Second is the issue of postwar settlements and perceptions of history.

Unlike other developed countries such as the U.S., the U.K. or France, Japan had to handle postwar settlements as a top diplomatic agenda in its relations with the governments of both Taiwan and China.

In other words, building a foundation for a diplomatic relationship with Beijing was postwar Japan’s one and only China policy goal, and Tokyo put in a great amount of effort to achieve it.

It was not the kind of goal that could simply be achieved with the conclusion of a peace treaty.

Third, in providing official development assistance (ODA) to China, Japan regarded it as an alternative to war reparations and, at the same time, tended to prioritize pursuing mutual economic benefits rather than political strategies.

Moreover, it is widely recognized in Japan that its ODA supported China’s modernization and economic growth. And it is true that such assistance strengthened economic ties between the two countries and nurtured mutual benefits.

The Foreign Ministry’s review of Japan’s ODA to China says: “Since 1979, ODA to China has contributed to maintaining and promoting the Reform and Opening Up Policy of China, and at the same time, it has formed a strong foundation to support Japan-China relations.”

Japan’s cooperation toward boosting the Chinese economy was inseparably interlocked with the issue of wartime settlements and perceptions of history.

The Foreign Ministry also said in 2018 that new ODA projects would be terminated in fiscal 2018 and all multiyear projects would be concluded by the end of fiscal 2021. This means that the end of fiscal 2021 in March this year represented the completion of a period in the postwar history of Japan-China relations.

Because of these reasons, it has been difficult for Japan to proactively plan a China strategy from long-term perspectives.

Japan’s China policy has so far been focused on short-term efforts to repair the relationship when it deteriorated, as well as on strengthening economic cooperation and friendship.

However, such times are coming to an end. We are now facing an era in which Japan needs to create a desirable China strategy on its own initiative, taking into account its long-term national interests.

Establishing ties

Then what is a desirable China strategy for Japan?

Japan’s China policy has been based on supporting China’s economic growth through ODA, regarding it as being in Japan’s national interests and hoping Beijing will play a constructive role in the Asia-Pacific region. But this is being forced to change.

Japan and China normalized diplomatic ties in 1972, thanks to great contributions by Prime Minister Kakuei Tanaka, who headed the Liberal Democratic Party’s middle-of-the-road Keiseikai faction, and Foreign Minister Masayoshi Ohira, who headed the party’s liberal Kochikai faction.

Meanwhile, the party’s conservative Fukuda faction headed by Takeo Fukuda had many pro-Taiwan lawmakers who were cautious about cutting ties with Taiwan and establishing diplomatic ties with the communist regime in Beijing.

The 1972 system stepped up further in 1978 when the Fukuda administration signed a peace and friendship treaty with China. This was a major step in that support for boosting economic ties and friendly relations with China had been established within the LDP regardless of factions.

The largest opposition Japan Socialist Party had been even more active than the LDP in developing ties with Beijing, and the Foreign Ministry’s China school had also been backing such efforts behind the scenes.

Such a consensus eroded gradually with the end of the Cold War and due to change in the power balance between Tokyo and Beijing brought about by Japan’s economic slowdown.

Furthermore, the current international environment largely differs from the Cold War era when the 1972 system was established.

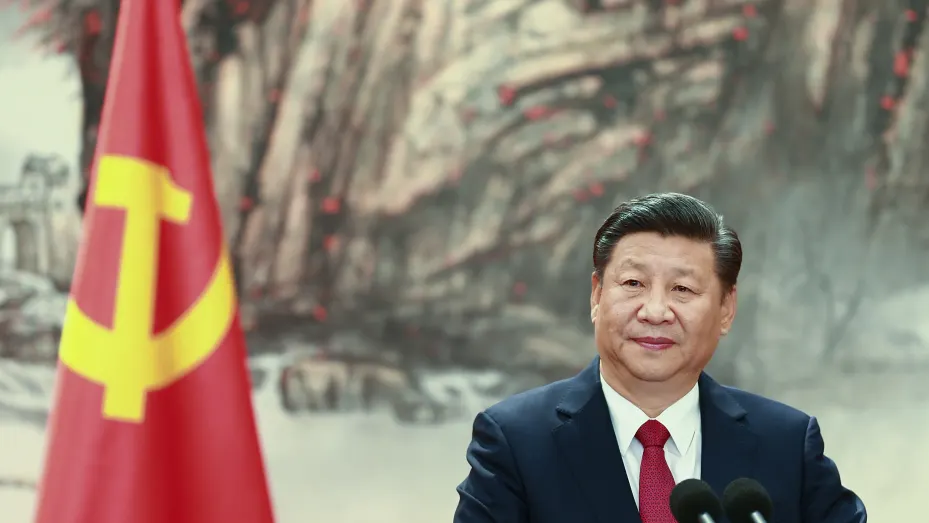

China and Russia are now demonstrating a cooperative relationship, effectively working together like allies. A joint statement issued following a meeting between Xi and Russian President Vladimir Putin on Feb. 4 said, “Friendship between the two states has no limits, there are no ‘forbidden’ areas of cooperation, strengthening of bilateral strategic cooperation is neither aimed against third countries nor affected by the changing international environment and circumstantial changes in third countries.”

As two authoritarian regimes — China and Russia — deepen cooperation while democracies including Japan and Western countries enhance their partnerships, the international society is being increasingly divided into two camps, centered around the two sides of U.S.-China confrontations.

Japan must consider a China strategy by setting the framework for future China-Japan relations in a broader context of the changing global balance of power.

Japan’s diplomacy

Taking into account such changes in the global community, the government should make use of the meeting of the four ministers — the prime minister, the foreign minister, the defense minister and the chief Cabinet secretary — within the National Security Council and come up with a long-term basic policy to place the China strategy at the core of the nation’s security strategy.

Amid increasing tensions between Washington and Beijing, Japan needs to strengthen deterrence against China based on the U.S.-Japan alliance and at the same time maintain and boost multilayered communications with China, making diplomatic efforts to stably develop China-Japan ties to a certain extent.

On top of this, unlike the U.S., it is also important for Tokyo to take part in the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership free trade agreement to proactively facilitate regional economic cooperation in East Asia in view of Japan’s national interests.

It is possible to advance cooperation with China for regional economic development while stepping up deterrence against Beijing and restricting economic relations with the country in certain economic areas from the perspective of economic security.

Completion of all ODA projects in China at the end of fiscal 2021 in March indicates an end to one era after World War II.

This means it is important for Japan to plan a long-term China strategy for the next 50 years within this year — the 50th anniversary of the normalization of diplomatic ties with Beijing — and share it within the government and also with the Japanese people.

Find the original article on the website The Japan Times

https://www.japantimes.co.jp/opinion/2022/06/30/commentary/japan-commentary/japan-china-strategy/

CAMBRIDGE – When the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, Ukraine inherited part of its nuclear arsenal. But in the 1994 Budapest Memorandum, Ukraine agreed to return these weapons to Russia in exchange for “assurances” from Russia, the United Kingdom, and the United States that its sovereignty and borders would be respected. Russia brazenly violated this promise when it annexed Crimea in 2014, and tore up the Memorandum with its full-scale invasion of Ukraine on February 24. Many observers have concluded that Ukraine made a fateful mistake by agreeing to surrender its nuclear arsenal (once the world’s third largest). Are they right?

n the early 1960s, US President John F. Kennedy predicted that at least 25 states would have nuclear weapons by the following decade. But in 1968, United Nations member states agreed to a non-proliferation treaty that restricted nuclear weapons to the five states that already had them (the US, the Soviet Union, Britain, France, and China). Today, just nine states have them – the five named in treaty signatories plus Israel, India, Pakistan, and North Korea – but there are more “threshold states” (countries with the technological ability to build nuclear weapons quickly) considering the option.

Read the entire article in Project Syndicate.