KEMAL DERVIŞ, Project Syndicate

French President Emmanuel Macron initially described his new political movement as being “neither on the right nor on the left,” and now says that it is “on both the right and the left.” But he won’t be able to fudge it indefinitely: sooner or later, he will have to pick a side with which to ally.

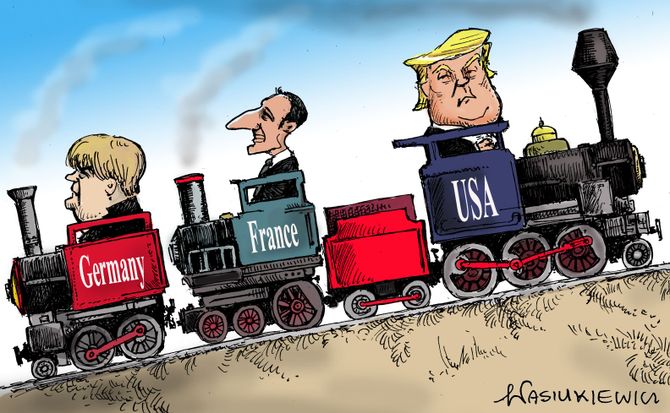

WASHINGTON, DC – French President Emmanuel Macron’s state visit to the United States last month was a study in contrasts. Despite the friendly dynamic, Macron’s agenda and rhetoric were almost diametrically opposed to US President Donald Trump’s. But Macron’s leadership is subject to an even more fundamental challenge; how he manages it could point the way forward for liberal-democratic politics.

Addressing the US Congress in English, Macron articulated a staunchly internationalist worldview, calling for stronger international institutions, a recommitment to the rules-based system of international trade, and a general embrace of globalization. With regard to Iran, he reiterated the need to preserve the 2015 nuclear deal, from which Trump has just withdrawn, though he did call for complementary agreements on topics that the existing agreement does not address.

Macron has also signaled that he will pursue a pan-European campaign for the 2019 European Parliament election. As a democrat, he believes that the deepening of the European Union must go hand in hand with the development of a truly European political space.

At a time of much hand-wringing over the decline of liberalism, the future of social democracy, the rise of nationalism, and the backlash against globalization, Macron’s unapologetically internationalist stance is notable. In fact, Macron has taken a leap into the unknown of the West’s “new politics,” a terrain no longer defined entirely by competition between large center-right and center-left parties. But is politics really turning the page on the traditional right-left cleavage?

It would be wrong to describe Macron, who served as a minister in his predecessor François Hollande’s Socialist government, simply as a centrist. Although he has moved toward the center, he did not join one of the small traditional centrist parties, but instead created his own “movement.”

Early on, Macron described that movement – which he called En Marche ! – as “neither on the right nor on the left” – avoiding the term “centrist.” Now, he says it is on “both the right and the left,” signaling his desire to win over traditional center-left and center-right voters.

If the traditional left-right divide is blurring, however, the question is what will replace it. With globalization at the center of political debate in most countries, it may seem that the answer is a division between cosmopolitan and parochial forces.

According to this interpretation, Macron leads France’s pro-globalization (and pro-European) movement, and those who oppose him, on the right or the left, are linked by a shared opposition to economic openness. And, indeed, the far right and the far left are espousing similar economic messages.

Meanwhile, existing center-left and center-right political parties – in France and throughout the West – tend to comprise internationally oriented factions and those who are more suspicious of globalization. If globalization is becoming the main electoral cleavage in Western countries, these two camps, the logic goes, are likely to split and form new political families.

Yet, while I believe there will be some movement in this direction, the traditional left-right cleavage seems unlikely to disappear. Traditional parties will continue to debate issues concerning income distribution, including the progressivity of tax systems and the proper scope and aims of social policy. The globalization “platform” alone will not be robust enough to define a large political party.

This means that in the coming years, Macron will have to align himself more closely with either the center-right or the center-left. The particular circumstances that enabled his electoral victory in 2017 – a discredited center-left, and a center-right candidate disqualified by scandal – will not reproduce themselves. He will have to become an internationalist left-leaning leader or an internationalist right-leaning one.

Only one of those appears to be a tenable option. The traditional policies of the center-right would not easily be compatible with a strong internationalist bent. If globalization, in its various dimensions, is to be backed by a popular majority, it will have to be accompanied by modernized social policies that provide effective help to those who need it. At a time of continuous economic disruption, this will be all the more important.

Economic openness demands social solidarity. That does not means protecting specific jobs from trade competition or technological innovation. It means assisting people to adapt to continuous change, by providing all citizens with the necessary resources, such as education, accessible health care, and transitional support. In short, a popular pro-globalization stance must be accompanied by a new social contract – backed by public resources – that appeals to a large majority. Otherwise, the siren song of neo-nationalism will be difficult to resist.

While completing the necessary tax and labor-market reforms on which he has embarked, Macron will need to address this challenge. In the current political paradigm shift, those who favor openness will outshine nationalist unilateralism only by adopting as their primary objective a modernized approach to social solidarity.