Patrick Nicolet is Capgemini’s Group Chief Technology Officer responsible for the technology, innovation and corporate venture agenda for the organization. Throughout his career Patrick has held a number of executive leadership and operational excellence roles such as Chairman of the Board of Capgemini Brazil and Executive Leader for India Operations. It was during this tenure that Patrick successfully led the integration of 30,000 new colleagues into Capgemini following the acquisition of iGate. He started his career in operations by turning around businesses notably as partner of the corporate recovery practice of Ernst & Young Switzerland and later within Capgemini as Group sales director or CEO of the Infrastructure Services business. Patrick has been recognized by the World Economic Forum as a Global Leader for Tomorrow at Davos (the precursor to the Forum for Young Global Leaders).

Carlos Moreira WPC – Health

Founder, Chairman and CEO of WISeKey. Before founding his company in 1999, he served as United Nations Expert on cybersecurity during 17 years. He is recognized worldwide as an Internet pioneer and has a unique profile, which combines extensive high level international diplomacy experience and emerging technologies expertise. He has received many international awards for his commitment to secure the Internet. He is very active in disruptive cryptotechnology, AI, blockchain, IoT and cybersecurity. He is also an expert in M&A, fundraising, IPOs, and listed companies. He is the coauthor of The transHuman Code bestseller book.

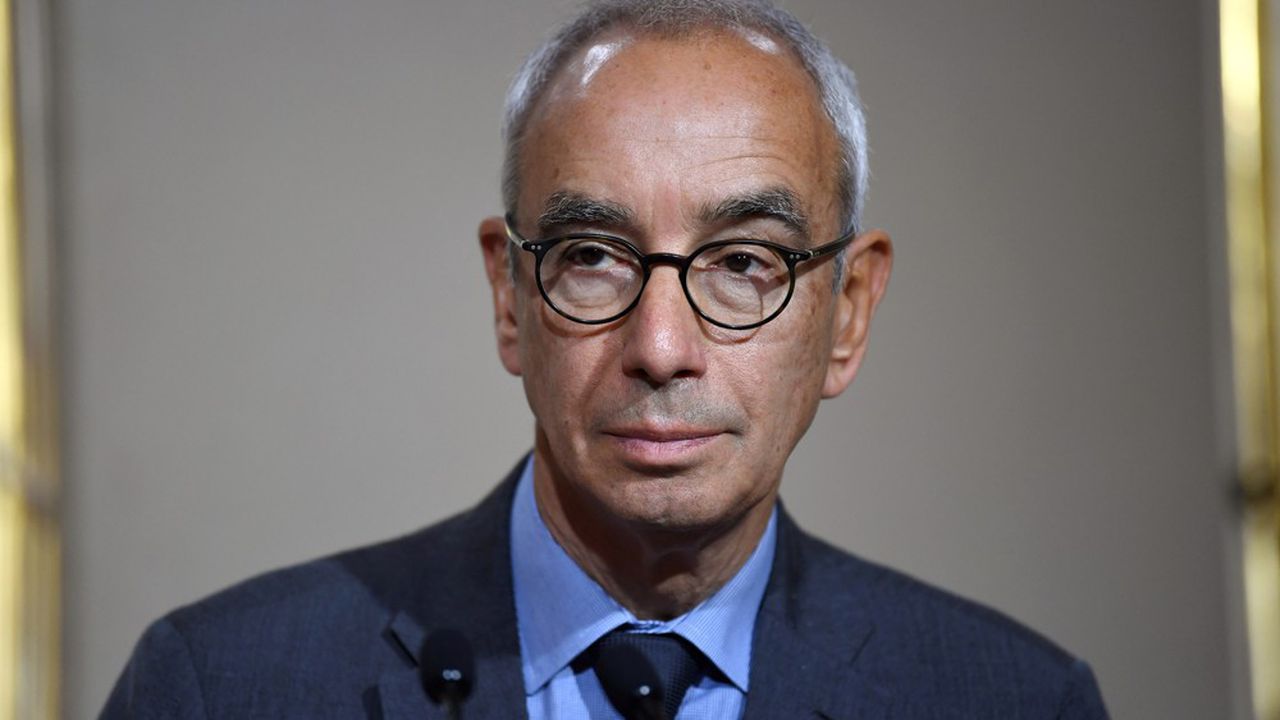

Thierry de Montbrial WPC – Health

Thierry de Montbrial is Executive Chairman of the French Institute of International Relations (Ifri), which he founded in 1979. He is Professor Emeritus at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Métiers. In 2008, he launched the World Policy Conference. He has been a member of the Académie des Sciences Morales et Politiques of the Institut de France since 1992, and is a member of a number of foreign academies. He serves on the board or advisory board of a number of international companies and institutions. Thierry de Montbrial chaired the Department of Economics at the Ecole Polytechnique from 1974 to 1992. He was the first Chairman of the Foundation for Strategic Research (1993- 2001). Entrusted with the creation of the Policy Planning Staff (Centre d’analyse et de prévision) at the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs, he was its first Director (1973-1979). He has authored more than twenty books, several of them translated in various languages, including Action and Reaction in the World System – The Dynamics of Economic and Political Power (UBC Press, Vancouver, Toronto, 2013) and Living in Troubled Times, A New Political Era (World Scientific, 2018). He is a Grand Officer of the Légion d’honneur, Grand Officer of the Ordre National du Mérite. He has been awarded the Order of the Rising Sun – Gold and Silver Star, Japan (2009), Commander of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany (2016) and other state honors by the French and several foreign governments. Thierry de Montbrial is a graduate of the Ecole Polytechnique and the Ecole des mines, and received a Ph.D. in Mathematical Economics from the University of California at Berkeley.

Les élections américaines et au-delà

Éditoriaux de l’Ifri, 12 octobre 2020

J’écris ces lignes alors que l’incertitude règne encore sur l’état de santé de Donald Trump, ce qui ajoute une inconnue à l’équation déjà compliquée du 3 novembre prochain. Dans une perspective à court terme, le contexte de l’élection ne serait cependant bouleversé que si le président sortant ne pouvait pas se présenter. Autrement, ce nouvel avatar dans une campagne déjà à nulle autre pareille ne devrait pas changer fondamentalement les choses.

Quel que soit l’élu, l’Amérique restera divisée comme jamais depuis la guerre de Sécession, avec de nouvelles explosions de violence et une mise sous tension inédite de la Constitution, dont chacun sait qu’elle est le pilier de l’identité américaine. Si un autre que Trump est élu, ce sera par défaut, comme ce fut le cas pour Trump face à Hilary Clinton en 2016.

Les prochaines années seront agitées aux États-Unis. La dépendance de la politique extérieure vis-à-vis de la politique intérieure a peu de chances de se distendre. Qu’il s’agisse de la rivalité avec la Chine ou du centrage sur les intérêts israéliens de la politique au Moyen-Orient, par exemple, on voit mal un Joe Biden faire significativement marche arrière. Beaucoup d’Européens veulent croire qu’avec l’ancien vice-président d’Obama on en reviendrait au bon vieux temps de la concertation transatlantique et du multilatéralisme. En apparence, peut-être. Mais en apparence seulement, car la dérive des continents a commencé avec l’émergence du monde post-soviétique, c’est-à-dire plus ou moins au début du nouveau siècle. Cette dérive s’explique par des facteurs objectifs, principalement la montée de la Chine et l’abaissement de la Russie. La personnalité des hôtes successifs de la Maison-Blanche ne peut qu’en forcer ou en atténuer les traits. Ce détail n’est cependant pas insignifiant. Pour arriver à ses fins en politique intérieure, Trump n’a pas hésité à rompre avec tous les codes en politique extérieure. Il a fait des émules jusqu’en Grande-Bretagne avec Boris Johnson. Du point de vue de la stabilité du monde dans son ensemble, le mépris du droit et des institutions internationales est pire qu’un crime. C’est une faute à l’égard du monde, et donc aussi me semble-t-il à l’égard des États-Unis. De ce point de vue, un autre que Trump pourrait peut-être calmer les blessures, mais pas changer le cours des choses. C’est la raison pour laquelle certains, de ce côté de l’océan Atlantique, espèrent la réélection du milliardaire. Selon eux, seul un tel choc pourrait consolider le timide mouvement des Européens en faveur de leur souveraineté.

Pour ma part, je me refuse à pareilles spéculations. D’abord, parce que les Européens ne sont que des spectateurs de la scène politique américaine. Ils n’ont aucun moyen de l’influencer. Ensuite et surtout, au nom du réalisme : dans tous les cas de figure, un minimum d’entente euro-américaine est nécessaire pour que les pays occidentaux, et ceux de tous les continents auxquels ils sont liés par l’histoire et la géographie, affrontent en souplesse le défi de la montée des puissances illibérales. Il y a aussi le défi de l’islamisme politique, incompatible avec les valeurs occidentales, et a fortiori la menace persistante du terrorisme islamiste. La nécessaire entente euro-américaine suppose cependant que les États-Unis, avec ou sans Trump, cessent de traiter les Européens comme des adversaires, en leur imposant brutalement leurs propres choix notamment par la voix des sanctions. Ayant dit cela, il faut reconnaître qu’un Trump II aurait peu de chances de se distinguer vraiment d’un Trump I. Dans ce cas, l’Union européenne n’aurait d’autre choix que de chercher les moyens de sortir des griffes de l’oncle Sam sans tomber dans celles de la Cité interdite. Le point le plus délicat est qu’à ce stade rien ne nous permet de penser qu’une Amérique à nouveau démocrate ne chercherait pas elle aussi à imposer sa volonté aux Européens, certes en y mettant un peu plus les formes.

Pour compléter ces propos pré-électoraux, prenons encore davantage de recul, avec un regard plus sociologique sur le monde contemporain. En premier lieu, on observe le rejet de toute notion d’autorité en général. Particulièrement spectaculaire à cet égard est l’effondrement du christianisme dans le monde occidental, incroyablement rapide à l’échelle de l’Histoire. Cela est vrai globalement du catholicisme mais aussi des protestantismes, particulièrement au profit des églises évangéliques. Ce dernier point est frappant aux États-Unis, où ce qui reste de la culture protestante, si importante pour l’identité de la première puissance mondiale, se trouve transfiguré dans des communautarismes sectaires d’autant plus irréalistes et intolérants qu’ils se sont coupés de leurs racines. Par analogie, comment ne pas faire un parallèle avec l’idéologie communiste, ce travesti du christianisme où l’on avait remplacé Dieu par « le peuple » et l’Église par le Parti. En Europe de l’Est, les églises orthodoxes résistent encore. Dans l’avenir proche, c’est peut-être aux États-Unis que la perte d’identité est la plus frappante, malgré les tentatives pour la dissimuler. En fin de compte, le phénomène Trump ne traduit-il pas la crispation d’une moitié de la population qui craint sincèrement la disparition des valeurs américaines ? La peur identitaire ne se manifeste pas qu’aux États-Unis. Elle est visible en France, et depuis longtemps. En fait, en dehors de l’orthodoxie en Russie, s’il est un monothéisme qui depuis un demi-siècle n’a cessé de renforcer ses positions, sur le plan tant religieux que politique, c’est l’islam. Et, depuis les décolonisations au sens large, l’islam politique a tendu à dégénérer dans les pires formes d’obscurantisme.

Après ou plutôt à côté de la religion, je citerai les réseaux sociaux et la conception libertaire qui prévaut encore à leur sujet. Il aura fallu beaucoup de temps pour qu’on commence à reconnaître que des segments entiers d’opinions publiques sont conditionnés par le déferlement continu de propos ou d’« informations » non contrôlés. Et les jugements éthiques à leur sujet ne coulent jamais de source. Les problèmes posés aux sociétés contemporaines sont extrêmement complexes. On ne peut traiter ces questions qu’en examinant toutes leurs faces et aucune synthèse parfaite n’est possible. Quand plus aucune autorité n’est reconnue, manipulateurs et cyniques ont le champ libre pour propager la « post-vérité » et justifier leurs crimes. La technologie est un formidable instrument sur lequel ils peuvent s’appuyer. Sans doute, le temps passant, la nécessité de légiférer sur l’internet se fera-t-elle de plus en plus sentir. Mais avant qu’un droit nouveau n’émerge, combien de drames se seront-ils déroulés, et avec quels effets ?

Pour mémoire, mentionnons sans commentaires l’explosion des inégalités pendant le temps de la « mondialisation heureuse », la surexploitation de la nature et les manifestations de plus en plus tangibles du changement climatique. Autant de faits qui, à eux seuls, suffiraient à expliquer le retour de formes quasi-révolutionnaires du socialisme (ou leur apparition dans le cas des États-Unis), fort éloignés de la social-démocratie.

Enfin, il y a l’interminable pandémie de COVID-19. Elle nous oblige à reconsidérer la gouvernance mondiale en matière de santé, alors que la tendance – exacerbée par la pandémie – est à la déglobalisation et à l’affaiblissement du multilatéralisme. Cet affaiblissement est accru par la suspicion d’incompétence qui prévaut au moins dans les opinions occidentales, sur la capacité des gouvernants à mener des politiques publiques cohérentes et efficaces.

J’ajoute pour terminer que les régimes autoritaires ou totalitaires ne sont pas à l’abri des révolutions, en partie pour les mêmes raisons. Aucun pays de nos jours ne peut se mettre entièrement à l’abri du regard des autres. Les régimes apparemment les plus solides peuvent se trouver balayés en un clin d’œil. Le déséquilibre est un phénomène mondial. Le mieux que l’on puisse attendre du prochain président des États-Unis, c’est un peu plus de sagesse. La sagesse n’exclut pas la fermeté. Ce serait déjà un grand progrès pour le système international dans son ensemble.

Je vous donne rendez-vous après le 3 novembre.

Thierry de Montbrial

Fondateur et président de la WPC

Fondateur et président exécutif de l’Ifri

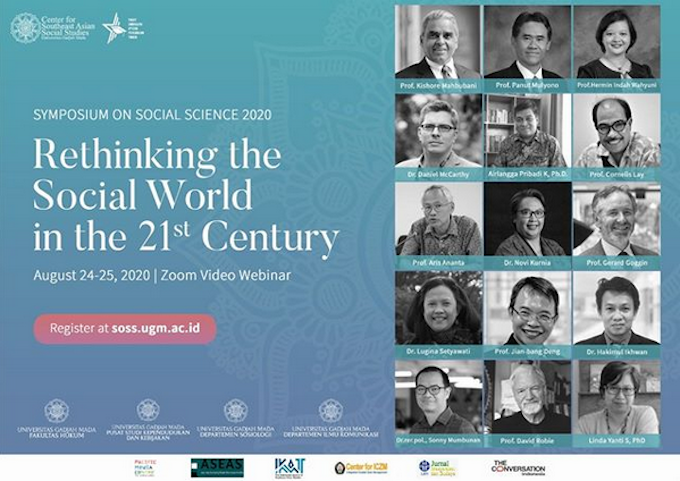

Franciscus Verellen et Jean-Pierre Cabestan, experts sur la Chine

4 Instituts Pour Mieux Comprendre La Chine D’Aujourd’hui

Forbes – 16.11.2020

Par Philippe Branche

“Quand on s’intéresse à la Chine : il est important de connaitre la pensée chinoise : d’Anne Cheng à Jacques Gernet en passant par Léon Vandermeersch”, explique le professeur Jean-Pierre Cabestan. A l’heure où le futur des relations diplomatiques avec la Chine est plus que jamais incertain avec l’élection de Joe Biden, le travail des sinologues est d’autant plus important. Peu connus du grand public, la France compte pourtant de nombreux instituts qui fournissent une intelligence de terrain pour les décideurs politiques et économiques. Retour pour Forbes France sur les différentes sources d’information pour comprendre la Chine d’hier et d’aujourd’hui.

Comprendre le passé de la Chine avec Franciscus Verellen – Ancien Directeur de L’École française d’Extrême-Orient (EFEO), membre de l’Institut.

L’École française d’Extrême-Orient (EFEO). Une institution qui a donné ses lettres de noblesse à la sinologie française. Sa mission scientifique vise l’étude des civilisations classiques d’Asie par le prisme des sciences humaines et sociales. Depuis sa création en 1898, l’École a connu une croissance constante avec un total de 18 centres et antennes en Asie : de Pondichéry, à la Thaïlande, en passant par Tokyo ou encore Hong Kong, et même un chantier archéologique en Corée du Nord.

L’EFEO n’aurait pas pu connaitre un tel essor sans les compétences apportées par ses enseignants-chercheurs. Franciscus Verellen, ancien directeur de l’École de 2004 à 2014 qui est aujourd’hui responsable du centre de Hong Kong, décrit l’École comme un exemple reconnu au plan international de « l’importance de la connaissance directe et acquise sur le terrain qui reste, encore aujourd’hui, une spécificité de la sinologie française ». Les implantations de l’EFEO sont considérées par les décideurs politiques et économiques comme une ressource fiable sur la Chine comme sur l’Asie.

Les travaux de Franciscus Verellen s’inscrivent dans la tradition d’excellence de la sinologie française. Son ouvrage « Imperiled Destinies : the Daoist Quest for Deliverance in Medieval China » retrace sur huit siècles l’ouverture du taoïsme à différentes influences et l’essor de la religion chinoise par excellence. Un livre passionnant pour comprendre l’évolution du taoïsme et ses liens complexes avec le bouddhisme et le confucianisme. L’expertise de Franciscus Verellen lui permet aussi d’avoir une compréhension subtile des enjeux religieux actuels en Chine. Lors de son intervention à la World Policy Conference créée par Thierry de Montbrial, le sinologue a mis l’accent sur la réponse politique au fait religieux dans l’Empire du Milieu. Selon lui, la Chine est un « État fondamentalement religieux » et ce renouveau spirituel a été provoqué par « la question des valeurs ». Depuis février 2018 le Front uni du parti communiste chinois régule et « sinicise » les cinq religions reconnues, taoïsme, bouddhisme, islam, catholicisme et protestantisme. Franciscus Verellen fait ainsi partie des sinologues dont le regard d’historien est précieux pour mettre en perspective des enjeux contemporains.

MERICS et l’Insitut Ricci – deux instituts internationaux pour l’actualité chinoise

La France n’est pas le seul pays européen à vouloir mieux comprendre la Chine contemporaine ; l’Allemagne s’y intéresse également. En 2013 fut établi le Mercator Institute for China Studies (MERICS), un think tank dédié uniquement à l’étude de la Chine. Les experts du MERICS se définissent d’abord comme “ouverts à de nouvelles perspectives sur la Chine et à de nouvelles propositions destinées à façonner les relations avec ce pays”. Leur dernier podcast, publié le 10 Novembre, ouvre des perspectives pour mieux cerner les enjeux d’actualité : “ US-Chine : les relations après les élections ”, un échange pour appréhender l’agenda chinois de Joe Biden. Ce think tank s’avère d’autant plus important que la Chine affiche malgré la pandémie mondiale un objectif de croissance annuelle du PIB de 5% pour les cinq prochaines années selon l’agence Reuters. De même, un autre institut plus ancien a pour objectif d’analyser les échanges culturels sino-occidentaux: l’Institut Ricci, dont le nom vient du premier prêtre Italien Matteo Ricci (1552-1610) à inaugurer l’inculturation du christianisme en Chine. Contrairement au MERICS qui se consacre principalement aux enjeux géopolitiques, ce dernier se consacre avant tout à l’étude de la civilisation chinoise et au dialogue interreligieux. Une conférence universitaire par Sophie Boisseau du Rocher (IFRI) devrait se tenir le 20 février 2021 prochain à Paris avec comme thème « Les Nouvelles Routes de la Soie, vues de l’Asie». Autant d’instituts donc pour mieux comprendre la Chine contemporaine d’un point de vue géopolitique et culturel.

Comprendre le présent du monde chinois avec Jean-Pierre Cabestan, ancien directeur du Centre d’études français sur la Chine contemporaine (CEFC)

Jean-Pierre Cabestan est directeur de recherche au CNRS et professeur à l’Université baptiste de Hong Kong. Il a été directeur du CEFC de 1998 à 2003 et s’intéresse tout particulièrement aux phénomènes politique en Chine populaire, à Hong Kong comme à Taiwan. Dans son ouvrage, ‘Chine-Taiwan, la guerre est-elle concevable?’, Jean-Pierre Cabestan d’une part analyse la menace chinoise et la capacité militaire, politique et économique de Taipei à résister. D’autre part, il évalue les risques de guerre et considère les différents scénarios possibles, avec ou sans implication américaine. Pour des sujets aussi sensibles et complexes, les experts comme Jean-Pierre Cabestan sont indispensables pour appréhender en profondeur cette zone de tension.

“En analysant l’histoire de la sinologie française, l’un des premiers pionniers de la recherche locale en Chine fut le général Jacques Guillermaz (1911-1998). Le général devient un observateur attentif des événements politiques de la Chine avec l’idée de l’étudier sur le terrain, une notion que de nombreux sinologues suivent encore aujourd’hui” explique Jean-Pierre Cabestan. “Le général a été l’un des fondateurs du Centre de recherche et de documentation sur la Chine contemporaine, qui fait maintenant partie de l’EHESS.” Dans son ouvrage Demain la Chine : démocratie ou dictature ? (publié en français et en anglais), Jean-Pierre Cabestan estime que le régime politique mis en place par Mao Zedong reste solide et doté d’une certaine capacité d’adaptation. Mais l’ancien directeur du CEFC pense qu’à plus long terme, du fait de la modernisation et la mondialisation de l’économie comme de la société chinoises, la question de la démocratie se posera, comme partout ailleurs.

Jean-Pierre Cabestan à la World Policy Conference ©

L’EFEO, le MERICS, l’Institut Ricci et le CEFC. Quatre instituts pour mieux apprécier la pluralité du monde contemporain chinois. Sans Franciscus Verellen ou Jean-Pierre Cabestan, il nous serait de plus en plus difficile d’appréhender le présent chinois. Par le biais d’un travail de recherches de terrain, nous comprenons qu’il y a non pas une mais différentes manières d’être chinois. “Ceux qui souhaitent bien connaître la Chine doivent se garder de prendre une partie pour le tout “ recommande finalement le Président chinois Xi Jinping.

Rozlyn Engel: Carnegie report on the U.S. foreign policy

Making U.S. foreign policy work better for the middle class

Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

Co-editors:

Salman Ahmed, Rozlyn Engel, Wendy Cutler, Douglas Lute, Daniel M. Price, David Gordon, Jennifer Harris, Christopher Smart, Jake Sullivan, Ashley J. Tellis, Tom Wyler

Summary

If there ever was a truism among the U.S. foreign policy community—across parties, administrations, and ideologies—it is that the United States must be strong at home to be strong abroad. Hawks and doves and isolationists and neoconservatives alike all agree that a critical pillar of U.S. power lies in its middle class— its dynamism, its productivity, its political and economic participation, and, most importantly, its magnetic promise of progress and possibility to the rest of the world.

And yet, after three decades of U.S. primacy on the world stage, America’s middle class finds itself in a precarious state. The economic challenges presented by globalization, technological change, financial imbalances, and fiscal strains have gone largely unmet. And that was before the novel coronavirus plunged the country into the worst economic crisis since the Great Depression, exposed and exacerbated deep inequities across American society, led long-simmering tensions over racial injustice to boil over, and launched a level of societal unrest that the United States has not seen since the height of the civil rights movement.

If the United States stands any chance of renewal at home, it must conceive of its role in the world differently. That too has become a point of rhetorical consensus across the political spectrum. But what will it actually take to fashion a foreign policy that supports the aspirations of a middle class in crisis? The Carnegie Endowment for International Peace established a Task Force on U.S. Foreign Policy for the Middle Class to answer that question. This report represents the conclusion of two years of work, hundreds of interviews, and three in-depth analyses of distinct state economies across America’s heartland (Colorado, Nebraska, and Ohio). It proposes to better integrate U.S. foreign policy into a national policy agenda aimed at strengthening the middle class and enhancing economic and social mobility. Five broad recommendations bear highlighting up front.

First, broaden the debate beyond trade. Manufacturing has long provided one of the best pathways to the middle class for those without a college degree, and it anchors local economies across the country, especially in the industrial Midwest. It makes sense, therefore, that so much of the debate about the revival of America’s middle class is centered around the effects of trade policy on manufacturing workers. But while millions of manufacturing jobs have been lost in the United States, other economic forces beyond global trade have also played a major role in the decline. In this sense, debates about “trade” are often a proxy for anxieties about the breakdown of a social contract—among business, government, and labor—to help communities, small businesses, and workers adjust to an interdependent global economy whose trajectory is increasingly shaped by large multinational corporations and labor-saving technologies.

Moreover, the majority of American households today sustain a middle-class standard of living through work in areas outside manufacturing, especially in the service sectors where the United States has competitive advantages. Many of these Americans generally support the trade policies of past decades that have largely served them well. In a February 2020 Gallup poll, 79 percent of Americans agreed that international trade represents an opportunity for economic growth.1 Many of these Americans are less concerned with overhauling past trade policies and are more preoccupied with how military interventions and changes in the United States’ global commitments, among other aspects of foreign policy, might affect their security and economic well-being.

Middle-class Americans are not a monolithic group. Their interests diverge. Different aspects of foreign policy impact them differently, including across gender, racial, ethnic, and geographic lines. Getting trade policy right is hugely important for American households but it is not a cure-all for the United States’ ailing middle class and represents only one element of a broader set of middleclass concerns about U.S. foreign policy.

Second, tackle the distributional effects of foreign economic policy. Globalization has disproportionately benefited the nation’s top earners and multinational companies and aggravated growing economic inequality at home. It has not spurred broad-based increases in real wages among U.S. workers. It has not driven a wave of public and private investments to enhance U.S. productivity generally and make more American workers and small businesses globally competitive. And while it has brought down the prices of certain highly tradable goods, it has done little to alleviate the growing pressure on American middle-class families from the rising costs of healthcare, housing, education, and childcare. Making globalization work for the American middle class requires substantial investment in communities across the United States and a comprehensive plan that helps industries and regions adjust to economic disruptions.

In particular, foreign economic policy will need to:

• prioritize international policies that will stimulate job creation and allow incomes to recover; • revamp the U.S. international trade agenda and ensure it is paired with a domestic policy agenda to support more inclusive economic growth;

• modernize U.S. and international trade enforcement tools and mechanisms to better combat unfair foreign trade practices that are especially harmful to small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and workers;

• pursue other international agreements that close regulatory and governance gaps across countries to improve burden-sharing and help address equity concerns; and

• craft a National Competitiveness Strategy that includes efforts to make U.S. SMEs and workers more competitive in the global economy and enhances the ability of communities to attract job-creating business investment.

Third, break the domestic/foreign policy silos. For decades, U.S. foreign policy has operated in a relatively isolated sphere. National security strategists and foreign policy planners have articulated national interests and set the direction of U.S. policy largely through the prism of security and geopolitical competition. That remains a critical perspective, especially at a time when geopolitical competition with China, Russia, and other regional powers is on the rise. But with so many Americans now struggling to sustain a middle-class standard of living, threats to the nation’s long-term prosperity and to middle-class security demand a wider prism—informed by a deeper understanding of domestic economic and social issues and their complex interaction with foreign policy decisions. That is not an easy shift to make. It will take better interagency coordination, interdisciplinary expertise, and some policy imagination. It will also require the contributions of a new generation of foreign policy professionals who break free of the mold cast during the Cold War and its immediate aftermath.

Fourth, banish stale organizing principles for U.S. foreign policy. National security strategists and foreign policy planners in Washington, DC, crave neat organizing principles for U.S. strategy. But there is no evidence America’s middle class will rally behind efforts aimed at restoring U.S. primacy in a unipolar world, escalating a new Cold War with China, or waging a cosmic struggle between the world’s democracies and authoritarian governments. In fact, these are all surefire recipes for further widening the disconnect between the foreign policy community and the vast majority of Americans beyond Washington, who are more concerned with proximate threats to their physical and economic security.

A foreign policy agenda that would resonate more with middle-class households and, in fact, advance their well-being, should:

• reinvigorate relations with close allies to build an agile and cohesive network that can effectively address the full range of diplomatic, economic, and security challenges—from pandemics and cyber attacks to unsecure weapons of mass destruction and climate change—that could imperil middle-class security and prosperity;

• manage strategic competition with China to mitigate the risk of destabilizing conflict and counter its efforts toward economic and technological hegemony;

• reduce the threat of a digital crisis and promote an open and healthy digital ecosystem;

• boost strategic warning systems and intelligence support to better head off costly shocks and build up protective systems at home;

• shift some defense spending toward research and development (R&D) and technological workforce development to protect the U.S. innovative edge and enhance long-term readiness;

• strengthen economic adjustment programs to improve the ability of middleclass communities to adjust to inevitable changes in the pattern of economic activity; and

• safeguard critical supply chains to bolster economic security.

This may seem like a somewhat less ambitious foreign policy agenda than might be expected from a task force comprised of foreign policy professionals who served in Democratic and Republican administrations from George H.W. Bush to Barack Obama. And to a large extent it is. That is the point. The United States cannot renew America’s middle class unless it corrects for the overextension that too often has defined U.S. foreign policy in the post–Cold War era. It is equally evident that retrenchment or the abdication of a values-based approach is not what America’s middle class wants—or needs.

Middle-class Americans have no illusion that their fate can be walled off from the fate of the world. They embrace the sense of enlightened self-interest that has motivated U.S. foreign policy over the past seven decades and want the United States to serve as a positive and constructive force around the world. They appreciate that U.S. foreign assistance cannot simply be about short-term transactional benefits for the United States but must serve a wider purpose. They understand that repressive regimes make the world less safe and less free, and that it is in the United States’ self-interest to stand up for human rights. All this requires a larger international affairs budget to retool American diplomacy and development for the twenty-first century.

Middle-class Americans interviewed also understand that the United States must sustain a strong national defense and that, moreover, it is in their economic interests. Defense spending and the defense industrial base are—and will remain for some time—the lifeblood for many middle-class communities across the country. That is why drastic cuts in the defense budget in the near term would be unwise. Instead of slashing the defense budget, a more prudent course would be to reduce defense spending gradually and predictably over the longer term, while shifting some resources toward a broader conception of national defense—to include workforce development, cyber security, R&D to enhance U.S. economic and technological competitiveness in strategic industries, pandemic preparedness, and the resilience of defense supply chains.

At the same time, middle-class Americans are concerned about the cost of U.S. interventions and the potential for political overreach. They want the country to exercise its power judiciously and to selectively seek out the best opportunities for effecting positive change. But to credibly assert global leadership, the United States must redress democratic deficits and social, racial, and economic injustice at home while seeking to reclaim the moral high ground abroad. The United States must get its own house in order.

Fifth, build a new political consensus around a foreign policy that works better for America’s middle class. None of the current major foreign policy approaches hold the key to American middle-class renewal—be it post–Cold War liberal internationalism, President Donald Trump’s America First, or progressives’ elevation of economic and social justice and climate change and the potential downsizing of U.S. defense spending. This may partly explain why no single view commands broad-based bipartisan support. In fact, despite the variation in middle-class economic and political interests, their foreign policy preferences point the way toward a potential new foreign policy consensus that is not yet reflected in today’s highly polarized political class.

A Gallup poll from February 2019 showed that 69 percent of Americans thought the United States should take a major or leading role in world affairs, a figure that has been relatively stable for a decade. There is simply very little public support for Trump’s revolution in U.S. foreign policy and its call to turn back the clock on globalization and international trade, constrain legal immigration, gut foreign aid, abandon U.S. allies, or abdicate U.S. leadership on the global stage. But that should not be overinterpreted as support for the restoration of the foreign policy consensus that guided previous Republican and Democratic administrations. That set of policies left too many American communities vulnerable to economic dislocation and overreached in trying to effect broad societal change within other countries. America’s middle class wants a new path forward.

A foreign policy that works better for the middle class would preserve the benefits of business dynamism and trade openness—which does not feature prominently enough in the progressive agenda—while massively increasing public investment to enhance U.S. competitiveness, resilience, and equitable economic growth. It would sustain U.S. leadership in the world, but harness it toward less ambitious ends, eschewing regime change and the transformation of other nations through military interventions. And it would recognize that a foreign policy that works for the middle class has to be connected to a domestic policy that works for the middle class.

Taken collectively, the task force’s recommendations provide a blueprint for rebuilding trust. So much of what is required to make U.S. foreign policy work better for the middle class will not be visible to, or verifiable by, most Americans at the local level. And in many instances, it will require working through difficult trade-offs, where the interests of industries, workers, or communities do not align. The American people need to be able to trust that U.S. foreign policy professionals are managing this tremendous responsibility as best they can, with the interests of the middle class and those striving to enter it at the forefront of their consideration.

U.S. foreign policy professionals will also need to regain the trust of U.S. allies and partners, which no longer have confidence that the deals struck with one U.S. administration will survive the transition to the next or that basic alliance structures that have endured for decades are still a given. As a result, they are increasingly hedging their bets, trying to stay in the United States’ good graces while also keeping their options with China and other U.S. rivals open.

Restoring predictability and consistency in U.S. foreign policy requires building broad-based political support for it. And the best and perhaps only viable path right now to rebuilding such support lies in making U.S. foreign policy work better for the middle class. The ideas in this report represent a starting point for discussion—one that will hopefully lead to healthy debate and bring many more innovative and actionable ideas to the table.

This publication can be downloaded at no cost at https://carnegieendowment.org/specialprojects/usforeignpolicyforthemiddleclass/.

Antoine Flahaut : Covid-19, peut-on continuer à tracer tous les cas contacts?

16.10.2020 – Heidi News

par Kylian Marcos

Les concepteurs de SwissCovid, application de traçage de contacts à l’échelle nationale, ont annoncé travailler sur une autre application destinée aux évènements privés. Dans plusieurs cantons, le traçage numérique des cas contacts est de rigueur, plusieurs applications se disputant le marché. Malgré cela, les services de santé publique sont proches de la rupture dans certains cantons, comme Genève. Se pose la question de la stratégie de traçage à adopter face à l’essor de nouveaux cas Covid-19.

Changer de focale. Le 15 octobre, dans son rapport quotidien, l’OFSP annonçait 2613 nouveaux cas en Suisse. A chaque fois, des personnes en contact sont placées en quarantaine. Ils sont actuellement plus de 11’000, selon l’OFSP, contre 6000 au début du mois. Pour le Pr Antoine Flahault, épidémiologiste et directeur de l’institut de santé globale de l’université de Genève, un changement de stratégie est nécessaire: […]

Antoine Flahaut est Directeur de l’Institut de Santé Publique à l’Université de Genève, et ancien directeur et fondateur de l’EHESP.

Laurent Fabius : La Covid est moins grave que le dérèglement climatique

16.10.2020 – Radio Classique

Antoine Mouly

La Covid est moins grave que le dérèglement climatique au regard de la gravité des phénomènes, selon Laurent Fabius

Laurent Fabius, président du Conseil constitutionnel était ce matin l’invité de Bernard Poirette. L’ancien président de la COP 21, à l’occasion de la sortie de son livre « Rouge Carbone » aux éditions de l’Observatoire, est revenu sur le changement climatique. Il en a notamment souligné le danger, affirmant que ses conséquences étaient plus graves que celle de la Covid.

L’élection américaine sera décisive dans la lutte contre le changement climatique

Interrogé par Bernard Poirette sur les perquisitions chez Olivier Véran, Agnès Buzyn, Edouard Philippe et Jérôme Salomon dans le cadre de la gestion de la crise sanitaire, Laurent Fabius a expliqué que cette situation lui a « évidemment rappelé son parcours » et l’affaire du sang contaminé. Pour l’ancien premier ministre, c’est « une évidence que les politiques doivent être transparents ». Il estime par ailleurs qu’ « il ne faut pas de politisation de la justice ni de judiciarisation de la politique ». Il est également revenu sur la formule de Georgina Dufoix « responsable mais pas coupable » qui est selon lui une « formule malheureuse » interprétée par l’opinion, à tort, comme une formule exprimant que les politiques se défilent devant leurs responsabilités.

Ancien président de la COP 21, Laurent Fabius est revenu sur ce qu’il restait de l’accord de Paris. Pour lui, cet accord restera comme « le premier accord mondial signé par tous les pays du monde pour enrayer le changement climatique ». Il a expliqué que ce résultat a été le fait de trois piliers : « le scientifique, la société civile et le politique ». Estimant que les deux premiers piliers ont continué à travailler dans le bon sens, il a pointé du doigt le manque dans la sphère politique et l’inaction de certains gouvernements : « l’accord reste mais il faut que la volonté politique soit mise en œuvre ». Sur ce point, l’ancien premier ministre est optimiste et a expliqué au micro de Bernard Poirette quels sont ses trois espoirs. Pour lui, le premier espoir réside en l’Europe, qui a une politique qui « va dans le bon sens ». Ensuite, il estime que la Chine représente un espoir avec les récentes annonces de son président Xi Jinping : « le président chinois a annoncé vouloir la neutralité carbone en 2060 ». Mais pour le président du Conseil constitutionnel, la grande question concerne l’élection américaine qui se tiendra dans deux semaines : « Si Donald Trump est élu, ce sera la catastrophe, alors que si c’est Joe Biden, il réintègrera l’accord de Paris et fera pression pour le respecter ».

« La Covid est moins grave que le dérèglement climatique »

Laurent Fabius a expliqué ce qu’il appelle le « giga paradoxe ». Selon lui, au regard de la gravité des phénomènes, « la Covid est moins grave que le dérèglement climatique ». Il a en effet rappelé que le changement climatique cause plus de morts et a des conséquences à long terme plus grandes. Pour lui le grand effort à faire est « de faire prendre conscience que ce problème est tout aussi important que la Covid » et que nous devons « mobiliser toutes nos forces ». Un changement d’esprit doit s’opérer.

Selon l’actuel président du Conseil constitutionnel, « on ne peut pas se résigner » face à cette situation. Il a par ailleurs expliqué que le changement climatique ne sera pas un problème pour nos petits-enfants mais pour nous et que les « dégâts actuels sont déjà épouvantables ». Evoquant le recul des gaz à effet de serre pendant le confinement, il regrette que ces émissions « soient en train de repartir avec l’activité économique ». Il a affirmé la nécessité de « relances vertes et non pas brunes », des relances brunes qui risqueraient d’accroître encore plus les émissions de CO2 dans l’atmosphère. Laurent Fabius estime qu’il est indispensable d’ « intégrer la préoccupation environnementale à la relance économique ».

Enfin, Bernard Poirette l’a interrogé sur sa vision du futur. Laurent Fabius s’est dit « n’être ni optimiste, ni pessimiste mais volontariste ». Il a rappelé l’importance de tenir les engagements pris mais a aussi mis en garde expliquant qu’il faut aller plus loin. Le président du Conseil constitutionnel a expliqué que « si les engagements de Paris étaient respectés, nous limiterions le réchauffement à 3 ou 4 degré, alors que l’objectif est de 2 ». Ainsi, la COP de Glasgow qui se tiendra l’année prochaine aura un rôle déterminant pour évaluer à nouveau les objectifs.

Hélène Rey : « Le changement climatique ne pourra être combattu en réduisant l’activité économique »

14 octobre 2020 – Le Monde

Hélène Rey

L’économiste Hélène Rey préconise, dans sa chronique, de neutraliser l’effet de la taxe carbone sur la politique monétaire de lutte contre la hausse des prix.

Chronique. Emboîtant le pas de la Réserve fédérale américaine, la Banque centrale européenne (BCE) a décidé de réexaminer en profondeur sa stratégie de politique monétaire. Les pays européens s’étant engagés à atteindre une économie neutre en carbone d’ici à 2050, la BCE doit désormais réfléchir à la manière dont son cadre de politique monétaire peut contribuer à cette transition.

Bien que le traité sur le fonctionnement de l’Union européenne fasse du maintien de la stabilité des prix l’objectif principal du Système européen des banques centrales (SEBC), le texte énonce également que « sans préjudice de [cet] objectif… le SEBC apporte son soutien aux politiques économiques générales dans l’Union, en vue de contribuer à la réalisation des objectifs de l’Union, tels que définis à l’article 3 du traité sur l’Union européenne ». Selon cet article, l’Union « œuvre pour (…) une économie sociale de marché hautement compétitive, qui tend au plein emploi et au progrès social, et un niveau élevé de protection et d’amélioration de la qualité de l’environnement ».

Le changement climatique ne pourra être combattu en réduisant purement et simplement l’activité économique : une refonte des systèmes de production existants sera absolument nécessaire. La seule manière d’atteindre l’objectif zéro émissions d’ici à 2050 consiste à transformer nos modes de production, de transport et de consommation.

Chocs d’offre

L’un des moyens les plus efficaces pour y parvenir – voire le seul – consiste à augmenter le prix du carbone tout en accélérant la cadence de l’innovation technologique. Cette approche entraînerait toutefois inévitablement d’importants chocs d’offre. Le coût des intrants, en particulier des énergies, deviendrait plus volatile à mesure de l’augmentation du prix du carbone et du remplacement progressif des combustibles fossiles par les énergies renouvelables. De même, les transports et l’agriculture seraient également soumis à d’importants changements, potentiellement perturbateurs dans les prix relatifs.

Quel que soit le cadre monétaire dont conviendront les banques centrales, ce cadre devra pouvoir s’adapter aux changements structurels majeurs ainsi qu’aux effets sur les prix relatifs engendrés par la décarbonation. Dans le cadre actuel, la BCE cible l’inflation de la zone euro à travers l’indice des prix à la consommation harmonisé (IPCH). Or cet indice inclut les prix de l’énergie, ce qui le rend inadapté au défi de la décarbonation. L’inflation des prix du carbone étant décidée par les dirigeants politiques de l’UE, la BCE ne saurait tenter de pousser d’autres prix à la baisse dans l’IPCH alors même que le prix de l’énergie augmente, ce qui créerait des distorsions encore plus importantes.

Lire la suite de l’article (réservée aux abonnés) sur le site du Monde.

Europe’s futile search for Franco-German leadership

16 Oct 2020 | Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI)

Josef Joffe

For decades, France and Germany have been known as Europe’s ruling ‘tandem’ or ‘couple’, even its ‘engine’. Together, they aimed to work to unify the continent. But, to pile up the metaphors, the French want to drive the jointly leased Euro-Porsche, while the Germans insist on rationing the petrol money. As a long list of crises—from Belarus to Nagorno-Karabakh—now shows, the two countries are not following the same road map.

That’s not surprising. As former German foreign minister Sigmar Gabriel has put it, France and Germany ‘view the world differently’ and thus have ‘distinct interests’. The truth is that Franco-German divergence is almost as old as the European Union.

That division bedevils the current French and German leaders—President Emmanuel Macron and Chancellor Angela Merkel—as much as it did their towering predecessors, Charles de Gaulle and Konrad Adenauer, ever since the two of them linked hands across the Rhine 60 years ago. They were to turn ancient enemies into trusted friends. But states don’t marry. They obey interests, not each other.

When two powers are so closely matched, the issue always is, who leads, and who follows? The hyperactive Macron certainly wants to run Europe (as, truth be told, all of his predecessors in the Élysée Palace have sought to do). Meanwhile, the plodding Merkel keeps stressing German priorities.

The current divergence is also a matter of personalities. Temperamentally, Macron is the opposite of Merkel. Whereas Macron craves the limelight, Merkel, known at home as Mutti (mum), reads from a well-thumbed script about continuity and caution.

This is reflected in their foreign policies as well. Since he won the presidency in 2017, Macron has successively flirted with US President Donald Trump, Russia’s Vladimir Putin and China’s Xi Jinping, then turned away in disillusion from all three. France simply doesn’t play in their league. Merkel, by contrast, has kept her distance from Trump, Putin and Xi.

Macron has also pronounced the ‘brain death’ of NATO, echoing Trump’s description of the alliance as ‘obsolete’. But a German chancellor would be the last to turn off the lights at the alliance’s headquarters in Brussels. After all, NATO has guaranteed Germany’s security for 70 years—and at a steep discount.

The most recent Franco-German disagreements centre on the eastern Mediterranean, where Greece and Turkey—both NATO members—threatened to come to blows over gas exploration in contested waters. Macron was quick to side with Greece, dispatching warships and planes while promising arms. Last month, he hosted a summit in Corsica involving the leaders of six other Mediterranean EU member states to provide a counterweight against Turkey. Germany wasn’t there.

Merkel instead mumbles platitudes about a ‘multi-layered relationship’ with Turkey, which must be ‘carefully balanced’. German interests are clear: Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan is guarding the Turkish–Syrian border against an uncontrolled influx of Middle Eastern refugees who will head for Germany if given half a chance. Provoke him, and he can open the refugee spigot at will.

Then there’s the current flare-up between Armenia and Azerbaijan over Nagorno-Karabakh. Macron, Putin and Trump have urged the two countries to negotiate immediately, while Erdogan has sided with the Muslim Azerbaijanis against Christian Armenia. Germany, however, is merely ‘alarmed’, because Merkel can’t afford to alienate Erdogan.

After large parts of Beirut were levelled by a deadly explosion in August, Macron dashed off to Lebanon, pledging to organise an international donor conference without coordinating with Merkel. France, which controlled the Levant after World War I, wants to keep a foot in the door to maintain its regional influence; Germany has no strategic interests there and instinctively shies away from anything smacking of escalation. Different interests, different schemes.

Germany is also taking a hands-off approach to Libya, whose civil war has drawn in Russia, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Turkey and France. The best Germany can do in the Middle East is to arrange yet another peace parley in Berlin, as is the German habit.

This is just a short list of Franco-German foreign policy differences in the past few months. But it confirms the pattern: France likes to jump in, while Germany prefers to hang back. Merkel recently proclaimed ‘the hour of Europe’ in an ‘aggressive world’. But if France and Germany won’t pull together, how could the other 25 EU members?

The irreducible reason is structural. Twenty-seven do not add up to one, whether on Russia or Belarus, where President Alexander Lukashenko is dead set on wiping out the democracy movement. When the 27 tried to hash out sanctions against Belarus, tiny Cyprus refused unless the rest agreed to penalise Turkey over illegally exploring for gas in the Mediterranean.

That could have been anticipated. Cyprus is practically a Russian economic colony, and Lukashenko is Putin’s client. After weeks of wrangling, Cyprus finally relented. The EU will now sanction 40 Belarusian officials—a punishment that gives Lukashenko no reason to pack his bags.

The EU is the world’s second-largest economic power, ahead of China, and on paper has as many troops as the United States. But riches alone do not make a strategic actor. If they did, Switzerland would be a great power.

Of course, no European leader will ever fail to appeal to Europe’s common destiny. But in the EU’s case, ‘unity’ is often the opposite of ‘agency’, the capacity to act as a whole. A bloc of 27 states bound by a unanimity requirement on issues members consider essential will never be a strategic actor, because it will always be guided only by the lowest common denominator that all can accept.

Even if France and Germany ever do march in lockstep, the others will not fall into line, because they fear the duo’s domination. Unless and until they fuse into the United States of Europe, the EU’s member states will never leave vital strategic issues up to majority rule.

Joschka Fischer : La tragédie transatlantique

28 septembre 2020

Joschka Fischer

BERLIN – Entre les péripéties d’un duel sino-américain de plus en plus tendu et la persistance de la crise du Covid-19, le monde vit indubitablement un changement profond, historique. Des édifices apparemment immuables, bâtis voici de nombreuses décennies font soudain preuve d’une extrême malléabilité, ou disparaissent purement et simplement.

Dans les temps anciens, les événements sans précédents du temps présent auraient persuadé aux populations inquiètes de scruter les signes d’une apocalypse à venir. Outre la pandémie et les tensions géopolitiques, le monde est aussi confronté à la crise climatique, à la balkanisation de l’économie mondiale et aux profondes perturbations technologiques engendrées par la numérisation et l’intelligence artificielle.

Les jours ne sont plus où l’Occident – sous la houlette des États-Unis soutenus par leurs alliés, notamment européens – jouissait d’une primauté politique, militaire, économique et technologique incontestée. Trente ans après la fin de la guerre froide – quand l’Allemagne s’est réunifiée et que les États-Unis sont apparus comme l’unique superpuissance –, rien ne justifie plus l’hégémonie occidentale, et l’Asie orientale, avec une Chine de plus en plus autoritaire et nationaliste à sa tête, s’avance, prête, sans tarder, à la remplacer.

Mais ce n’est pas dans l’aggravation de la rivalité avec la Chine qu’il faut chercher l’affaiblissement de l’Occident. Ce sont ses développements internes qui, des deux côtés de l’Atlantique, ont presque entièrement précipité son déclin, particulièrement, quoiqu’il n’en ait pas l’exclusivité, au sein du monde anglo-saxon. Le référendum sur le Brexit au Royaume-Uni et l’élection aux États-Unis du président Donald Trump en 2016 ont marqué une coupure décisive dans ce qui avait été l’engagement transatlantique en faveur des valeurs libérales et d’un ordre mondial fondé sur des règles, et cette coupure présageait la résurrection d’une obsession bornée pour une souveraineté nationale sans avenir.

L’Occident transatlantique, idée qu’incarnait la création de l’OTAN après la Seconde Guerre mondiale, était le produit du triomphe militaire des États-Unis et du Royaume-Uni sur les théâtres pacifique et européen. Ce sont les dirigeants de ces deux pays qui ont créé l’ordre de l’après-guerre et ses principales institutions, des Nations Unies et de l’Accord général sur les tarifs douaniers et le commerce (le précurseur de l’Organisation mondiale du commerce) à la Banque mondiale et au Fonds monétaire international. En tant que tel, l’« ordre libéral du monde » – et bien sûr, d’une manière générale, l’« Occident » – était tout entier une initiative anglo-saxonne, dont la victoire à l’issue de la guerre froide renforçait encore la légitimité.

Mais au cours des décennies qui ont suivi, les forces du monde anglo-saxon se sont épuisées et, dans sa population, beaucoup se sont mis à rêver au retour d’un âge d’or impérial et mythique. La perspective d’une restitution de la grandeur passée est devenue, dans les deux pays, un slogan politique gagnant. Entre la doctrine de « L’Amérique d’abord » de Trump et les appels du Premier ministre du Royaume-Uni Boris Johnson à « reprendre le contrôle », le dénominateur commun est un ardent désir de revivre les temps idéalisés des XIXe et XXe siècles.

En pratique, ces slogans conduisent à un retour en arrière voué à l’échec. Les fondateurs de l’ordre international, qui ont consacré la démocratie, l’État de droit, la sécurité collective et les valeurs universelles, sont désormais occupés à le démanteler de l’intérieur, et par conséquent à détruire les fondements de leur propre puissance. Et cette autodestruction anglo-saxonne crée un vide, qui ne conduit pas à un nouvel ordre mais au chaos.

Certes, les Européens, à commencer par les Allemands, seraient malvenus à jouer les spectateurs complaisants ou à pointer du doigt les Anglo-Saxons. Parce qu’ils se sont trop peu intéressés aux questions de défense ou ont persisté à minimiser l’importance des surplus commerciaux, ils portent eux aussi une part de responsabilité dans la résurgence actuelle des nationalismes.

Si l’Occident, comme idée et comme bloc politique, veut survivre, quelque chose doit changer. Les États-Unis et l’Union européenne seront l’un et l’autre plus faibles s’ils sont séparés que s’ils forment un front uni. Mais les Européens n’ont aujourd’hui d’autre choix que de faire de l’Union un véritable acteur, en tant que tel, de la puissance. Une faille profonde s’est ouverte entre les Européens du continent – à qui revient la tâche de poursuivre la construction occidentale – et des Anglo-Saxons de plus en plus nationalistes.

Car le Brexit n’est pas vraiment affaire de pragmatisme et de relations commerciales ; il représente plutôt une rupture fondamentale entre deux systèmes de valeurs. Pour poser clairement la question, que se passera-t-il si Trump est réélu en novembre ? Il est presque certain que l’Occident transatlantique ne survivrait pas à quatre années supplémentaires, et l’OTAN devrait probablement faire face à une crise existentielle, même si les Européens augmentaient, conformément aux exigences des États-Unis, leurs dépenses de défense. Pour Trump et ses partisans, il ne s’agit pas vraiment d’argent. Ce qui leur importe d’abord, c’est la suprématie américaine et l’allégeance européenne.

Si, en revanche, l’ancien vice-président Joe Biden est élu, les relations transatlantiques prendront certainement un tour plus amical. Mais il n’y aura pas de retour à l’ère d’avant Trump. Même avec une administration Biden, les Européens n’oublieront pas facilement la profonde défiance semée au cours des quatre années qui se sont écoulées.

Quel que soit le vainqueur en novembre, les États-Unis devront compter avec une Europe qui accordera beaucoup plus d’importance à sa souveraineté, notamment pour ce qui concerne la technologie, qu’elle ne l’a fait par le passé. Les interdépendances complices des années qui ont suivi la guerre froide sont révolues depuis longtemps. L’Europe devra se montrer beaucoup plus attentive à la protection de ses propres intérêts, et l’Amérique comprendra opportunément que ceux-ci puissent diverger des siens.

François Barrault : La 5G, un enjeu géopolitique ?

BMF Business | 29 septembre 2020

Ce mardi 29 septembre, François Barrault, président de l’IDATE DigiWorld, est revenu sur les enjeux de la 5G et a parlé de son top départ pour la vente aux enchères des fréquences, dans l’émission Good Morning Business présentée par Sandra Gandoin et Christophe Jakubyszyn.

Good Morning Business est à voir ou écouter du lundi au vendredi sur BFM Business. Dans « Good morning business », Christophe Jakubyszyn, Sandra Gandoin et les journalistes de BFM Business (Nicolas Doze, Hedwige Chevrillon, Jean-Marc Daniel, Anthony Morel…) décryptent et analysent l’actualité économique, financière et internationale. Entrepreneurs, grands patrons, économistes et autres acteurs du monde du business… Ne ratez pas les interviews de la seule matinale économique de France, en télé et en radio.

Retrouvez l’article original et la vidéo de l’Interview sur BFM Business.

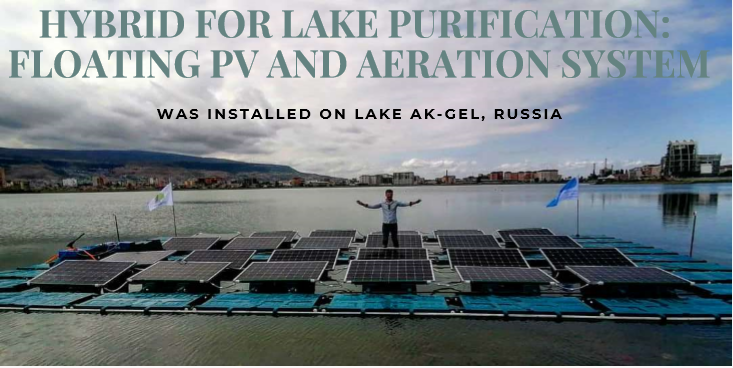

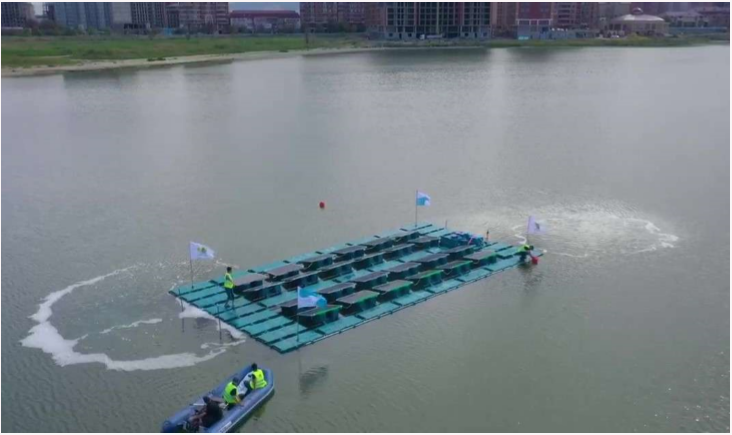

Polina Vasilenko: HelioRec installed the first in the world hybrid system for lake purification

HelioRec | September 2020, Issue 1

Fruitful cooperation between EcoEnergy and HelioRec

On 13th of September 2020 the first in the world hybrid system for lake

purification: floating PV and aeration system was installed on lake Ak

Gel. This lake is located in the center of Makhachkala (Dagestan

Republic, Russia) and it faces many serious ecological problems:

- Oxygen concentration is 3 times less than normal;

- Active algae growth;

- Water evaporation (area was reduced twice during the last 20 years).

Engineers from HelioRec, a Skolkovo innovation center resident, and EcoEnergy (project developers) invented the unique solution to solve these problems.

Floating power plant with the total area of 150 m2 that consist of:

- 24 floaters with 295W photovoltaic modules (Solar Systems);

- 36 footpaths;

- 4 batteries;

- 4 aerators which can help to bring needed amount of oxygen to revive the lake within 1 year.

In the process of developing the first project of its kind in the world,

engineers were required to apply fundamentally new solutions: aerators are powered by an autonomous solar generation with a 7 kW capacity based on a floating system, and “smart control technology” allows to control the power plant from a mobile phone. The system could survive the first storm (19th of September 2020) with wind speed more than 30 m/s. Based on the results of the first installation, HelioRec and Eco-Energy will decide about increasing size of the power plant and further project development.

Would like to build something innovative, let us know: savetheplanet@heliorec.com

See more of the project here.

Ana Palacio : The EU Merry-Go-Round

Project Syndicate | Sep 24, 2020

by Ana Palacio

EU leaders have tended to operate on the assumption that Europe is inevitable, and that Europeans are inescapably bound together in a community of fate. But many citizens don’t see it that way, and if they aren’t given a more convincing rationale for European integration, the only inevitability will be the EU’s demise.

Yes, the policies and actions Von der Leyen described are important. But, at this point, no policy will fortify the EU’s foundations sufficiently. No grand-sounding program or budget increase will ensure its progress. No amount of common debt will guarantee its survival. To survive and thrive, Europe needs an overarching vision that captures the breadth of the challenges it faces, establishes a sense of common purpose among all citizens, and galvanizes popular support.

EU leaders have long peddled a hollow concept of European citizenship, one that emphasizes rights, rather than responsibilities and shared burdens. They have shown what the EU does, but not what the EU is for. And many refuse so much as to discuss the question. They believe the answer to be self-evident: Europe is inevitable, and Europeans are inescapably bound together in a community of fate.

But many citizens don’t see it that way. If they aren’t given a more convincing answer, the only inevitability will be the EU’s demise.

There have been glimmers of hope that EU leaders recognize the need to engage European citizens actively. For example, as part of the messy compromise that led to her confirmation as Commission president in 2019, Von der Leyen floated the idea of a Conference on the Future of Europe – a platform for engaging citizens in a wide-ranging debate on what the EU should look like and how to achieve it.

But the initiative has been delayed due to the COVID-19 pandemic. And even if it is implemented, it will most likely go the way of other much-touted citizen-outreach efforts, such as the underwhelming European Citizens’ Consultations of 2018. Discussions will receive plenty of press, a report will be drawn up, and a communiqué released. Then another crisis will arise, and EU leaders will all but forget it. Its only lasting impact will be the resignation and even resentment felt by the citizens who participated.

The Conference on the Future of Europe was relegated to a single passing reference in von der Leyen’s address, as she discussed the post-pandemic organization of health competencies within the EU. Moreover, the European Council has already rejected the possibility of any treaty change stemming from the Conference. The more engaged citizens are with Europe, the less they will need their national governments to act as intermediaries. The same anxiety has fueled opposition to a European-level tax, which would make the EU directly accountable to citizens.

But if the initiative has no real stakes, it will attract no significant citizen buy-in. The same goes for the European project more broadly: if citizens feel no sense of ownership over the EU and no sense that their fates are tied to those of their fellow Europeans, they will never offer anything more than passive support. And passive support simply will not get the EU or its member states – to where they need to be.

It is preposterous that in 2020, 11 years after the eurozone crisis, the European Commission president is still calling to complete the banking union in her state of the union address. Her statement on migration – it is a “European challenge,” to which we can find a solution, “if we are all ready to make compromises” – was one that should have been made and agreed to in 2015, at the height of the migration crisis. Even her comment on Belarus rang hollow, given the EU’s failure to agree on sanctions against President Aleksandr Lukashenko’s regime. And round and round we go.

Bertrand Badré : « Il faut saisir ‘l’opportunité’ du Covid pour changer » le système économique

Europe 1 | 24 septembre 2020

Julien Ricotta

Bertrand Badré, un homme d’affaires réputé proche d’Emmanuel Macron, publie un livre pour appeler à repenser le modèle économique actuel. « Il faut saisir l’opportunité du Covid, entre guillemets, pour changer ce qui peut l’être », a-t-il déclaré jeudi soir sur Europe 1.

INTERVIEWLe système économique actuel va-t-il survivre au coronavirus ? Fragilisée de toutes parts par la pandémie de coronavirus, l’économie mondiale continue de souffrir, de l’Europe aux États-Unis en passant par la Chine. Bertrand Badré, un homme d’affaires réputé proche d’Emmanuel Macron, plaide pour une refonte du système capitaliste dans un livre intitulé Voulons-nous (sérieusement) changer le monde ? – repenser le monde et la finance après le Covid-19. « Il faut saisir l’opportunité du Covid, entre guillemets, pour changer ce qui peut l’être. A partir du moment où l’on investit des milliards et des milliards, on doit les mettre dans la bonne direction », a-t-il insisté jeudi soir sur Europe 1.

« On a gâché la crise précédente »

Le directeur de la société d’investissement Blue Like an Orange a pointé du doigt les failles du système actuel, héritées selon lui d’une mauvaise gestion de la précédente crise économique entre 2008 et 2011. « On a gâché la crise précédente, la crise financière dite des subprimes et de l’euro. A l’époque, on a colmaté les brèches mais on n’a pas repensé le système, qui a été rafistolé et qui a montré ses fragilités avec le Covid », a constaté le financier.

Bertrand Badré revendique tout de même être un défenseur du capitalisme. « La réalité, c’est qu’on continue à vivre et que le système a continué à vivre. On a fait en 3-4 mois ce qu’on avait fait en 3-4 ans il y a dix ans. La Réserve fédérale américaine et la Banque centrale européenne ont mobilisé 2.000 milliards d’euros en trois mois, ce qu’elles avaient mis trois ans à faire au cycle précédent », a assuré l’ancien directeur général de la Banque mondiale.

« Les inégalités vont croître mécaniquement »

Bertrand Badré s’est également alarmé de l’augmentation des inégalités. « On entre dans une période avec des taux très bas. Si vous avez un premier milliard, on vous en prête un deuxième avec zéro et avec lequel vous pouvez investir et gagner encore plus. Si vous n’avez rien, vous voyez le bateau passer », a-t-il déploré. « Les inégalités vont croître mécaniquement », a-t-il prévenu.

Retrouvez l’article original et la vidéo et l’Interview sur Europe 1.

Mathilde Pak : « Il faut déployer des formations au numérique pour que personne ne reste sur le côté »

Le Monde – 23.09.2020

Marie Charrel

Avec le coronavirus, bienvenue dans un monde sans contact

Travail, santé, industrie… le Covid-19 va intensifier une série de mutations déjà à l’œuvre. Cette numérisation à marche forcée risque de se faire au détriment de l’emploi et des relations sociales.

Il n’est pas doué pour la conversation, mais ses expressos sont réputés du tonnerre. Au Lounge’X, café à l’ambiance mi-industrielle, mi-traditionnelle de Daejeon, grande ville au centre de la Corée du Sud, le robot Baris, de son petit nom, agite son bras d’acier pour remplir les tasses des habitués, plus guère surpris de ce ballet mécanique. Dans le quartier chic de Gangnam, à Séoul, inutile de chercher le serveur dans le restaurant Mad for Garlic : les plats, payés par smartphones, sont servis aux tables par un chariot automatisé. Non loin, au Novotel Ambassador Dongdaemun, le client de l’une des 211 chambres commandant un sandwich au milieu de la nuit voit débarquer un robot aux allures de minibar ambulant. Dans les rues alentours, des voiturettes autonomes sont testées pour livrer achats en ligne et repas à domicile.

Travailler, déjeuner et faire ses courses dans l’une des plus grandes mégapoles d’Asie sans approcher un être humain de la journée : en Corée du Sud, la « société sans contact » ne relève plus de la science-fiction, et elle a pris un peu plus d’ampleur encore avec la pandémie liée au Covid-19. Depuis le début de l’année, le pays a renforcé le recours aux technologies permettant de limiter les interactions pour respecter la distanciation physique. Et le président Moon Jae-in a fait desdites innovations le grand axe de son ambitieux plan de relance de 76 trillions de wons (55,8 milliards d’euros), dévoilé en juin.

Interactions virtuelles

Dans le détail, celui-ci prévoit une série d’investissements pour aider 160 000 entreprises à muscler leurs systèmes de travail à distance, pour connecter 1 300 fermes et villages de pêcheurs à l’Internet haut débit, pour équiper 240 000 étudiants en tablettes, et pour accélérer une série d’inventions telles que robots, drones et véhicules autonomes. Fort de sa longueur d’avance dans le déploiement de la 5G, le pays du Matin-Calme se rêve en leader de l’économie « untact » − un bricolage coréen entre les mots anglais undo (« annuler », « défaire ») et contact.

L’expression a été forgée en 2017 par Rando Kim, spécialiste des tendances de consommation à l’Université nationale de Séoul, pour évoquer l’essor des interactions humaines virtuelles dans la consommation comme au travail, et l’utilisation de robots pour pallier le vieillissement de la main-d’œuvre. « La Corée du Sud était encore un pays pauvre au début des années 1960, elle fait preuve d’une grande capacité à changer très vite », explique Rando Kim. Avant de confier : « Je suis tout de même surpris que l’économie « untact » soit devenue populaire si rapidement. À cause de la pandémie, les gens ont peur de se toucher, et surtout, ils doivent l’éviter ».

Cette peur de la contagion, pas un continent n’y échappe aujourd’hui. En Europe, aux Etats-Unis, en Amérique du Sud, des millions de salariés ont basculé du jour au lendemain en télétravail et des millions d’entreprises ont adapté leur fonctionnement en catastrophe. Des restaurants se sont mis à la vente à emporter ou à la livraison. Des hôpitaux, comme La Salpêtrière à Paris, ont testé des robots pour permettre aux familles de visiter virtuellement leurs proches en réanimation.

« Nous sommes des animaux sociaux, nous avons besoin du contact physique avec les autres », Olivier Servais, anthropologue

Les logiciels permettant d’organiser des réunions virtuelles ont été pris d’assaut, sans parler de la foison de nouvelles start-up proposant des modules de prise de température par infrarouge ou des machines autonomes assurant la désinfection de lieux publics. « Il devient possible d’imaginer un monde économique – des usines aux consommateurs individuels – où les contacts humains sont minimisés », estime le cabinet McKinsey, dans un récent rapport, citant également le boom des téléconsultations de médecine.

A l’heure où les contaminations repartent en Europe, alors que l’incertitude quant à la possibilité de mettre au point un vaccin rapidement est forte, il est bien sûr impossible de prédire ce à quoi ressemblera le monde d’après. Dans le scénario où le Covid-19 serait maîtrisé au cours de l’année prochaine, il est néanmoins probable que nous retrouvions une partie de nos habitudes d’avant. « Nous sommes des animaux sociaux, nous avons besoin du contact physique avec les autres », rappelle Olivier Servais, anthropologue à l’Université catholique de Louvain.

« Amplificateurs de changements »

Mais pour le reste, la pandémie va sans doute intensifier durablement une série de mutations déjà à l’œuvre depuis plusieurs années. « Les crises sont toujours des amplificateurs de changements », résume Stefano Scarpetta, de l’Organisation de coopération et de développement économiques(OCDE). La récession de 2008 avait ainsi précipité la désindustrialisation aux Etats-Unis et cristallisé la question des inégalités en Europe. « Celle liée au Covid va marquer l’accélération du capitalisme numérique », estime Daniel Cohen, directeur du département d’économie de l’Ecole normale supérieure. Soit l’autre petit nom de l’économie « untact ».

Outre le recours massif au télétravail, l’expression la plus manifeste de ce basculement est l’envol des paiements sans contact. « Les Français s’y sont massivement convertis pendant le confinement, et ils le sont restés depuis : la crise a servi de déclic », note Julien Lasalle, secrétaire de l’Observatoire de la sécurité des moyens de paiement, à la Banque de France. Entre juillet et septembre, les retraits de billets aux distributeurs sont en baisse de 10% par rapport à la même période l’an passé, et les paiements en magasin avec saisie du code confidentiel ont chuté de 25%.

« En revanche, les paiements sans contact ont bondi de 65 % par rapport à 2019, favorisés par le relèvement du plafond de 30 à 50 euros, et les paiements par l’e-commerce ont progressé de 25 % », ajoute M. Lasalle. « La même tendance s’observe dans la plupart des pays européens : rarement un basculement aussi rapide des usages n’avait été observé », confirme Gilles Grapinet, PDG de Worldline, premier groupe de services de paiement en Europe.

De même, l’e-commerce a renforcé un peu plus encore son assise : les achats en ligne de produits de consommation courante ont progressé de 45,7 % au deuxième trimestre, selon la Fédération d’e-commerce et de la vente à distance (Fevad). Et ce, au profit des géants américains tels qu’Amazon. « Les petits commerçants s’y sont mis aussi pour compenser la baisse des visites en boutique, nuance M. Grapinet. Le taux de pénétration du numérique dans nos vies a gagné peut-être 3,5 voire 10 ans. »

Du côté des usines, contraintes de fonctionner avec moins de personnel, les robots, imprimantes 3Det autres machines autonomes se sont également rendus un peu plus indispensables encore. Au point de remplacer pour de bon une partie des ouvriers ? L’économie sans contact sera-t-elle une société sans travail ?

Polarisation des emplois

Depuis plusieurs années, déjà, l’automatisation des tâches soulève les inquiétudes, dans l’industrie comme dans les services. D’après l’OCDE, la numérisation pourrait engendrer la disparition de 14 %des emplois dans les grands pays industrialisés ces vingt prochaines années, tandis que 31,6 % des postes seraient profondément transformés. Au risque que cela accélère un peu plus encore la disparition des classes moyennes.

« Mais cela n’a rien d’inéluctable : tout dépend de la façon dont on s’emparera de ces technologies ces prochaines années », souligne Daniel Cohen, qui décrit ces mutations dans son dernier ouvrage, Il faut dire que les temps ont changé (Ed. Albin Michel, 2018). A l’hôpital, les robots remplaceront-ils les infirmiers pour les gestes simples ? Ou bien, en leur libérant du temps, leur permettront-ils de se consacrer un peu plus aux patients, voire de réaliser des tâches jusqu’ici dévolues aux médecins ? De même, le télétravail favorisera-t-il un meilleur équilibre entre vies personnelle et professionnelle, ou bien accélérera-t-il la délocalisation de postes de cadres vers les pays à bas coût ?

« Cela suppose de déployer des formations et de l’éducation au numérique pour que personne ne reste sur le côté, notamment parmi les petites entreprises », Mathilde Pak, spécialiste de la Corée à l’OCDE

Deux scénarios sont possibles pour l’avenir, explique Daniel Cohen. Dans le premier, la numérisation à outrance, utilisée pour réduire les coûts, intensifierait la polarisation des emplois et « conduirait à une forme de déshumanisation », creusant les inégalités. La Conférence des Nations Unies sur le commerce et le développement (Cnuced) s’en est alarmée dès le début de la pandémie : « Le passage rapide à la numérisation est susceptible de renforcer la position de quelques plateformes méga-numériques, prévient l’institution. Le fossé béant entre les pays sous-connectés et hypernumérisés va s’élargir. »

Dans le second scénario, les technologies numériques seraient utilisées en complémentarité des salariés, permettant notamment de pallier le vieillissement de la population active. « Cela suppose de déployer des formations et de l’éducation au numérique pour que personne ne reste sur le côté, notamment parmi les petites entreprises, les autoentrepreneurs et les plus âgés », souligne Mathilde Pak, spécialiste de la Corée à l’OCDE.

A Séoul, au début de la pandémie, des applications mobiles permettant de connaître en temps réel les stocks de masques dans les commerces ont fleuri. Grâce à elles, les jeunes ont réussi à s’équiper en quelques clics. Mais les retraités, eux, ont été des milliers à faire la queue pendant des heures devant les pharmacies de quartier, parfois en vain, car très peu ont su utiliser les applications. Rando Kim, le père de l’économie « untact », est le premier à en convenir : « Réduire cette fracture est l’un des défis que mon pays devra relever ces prochaines années. » Et pas seulement le sien…

Antoine Flahault : « Nous sommes peut-être en train d’observer les fondements de ce qui deviendra une deuxième vague »

L’épidémiologiste juge préoccupante la hausse des hospitalisations en France et en Espagne, mais souligne que la mortalité reste faible à ce stade en Europe.

Par Yves Bourdillon

Publié le 15 sept. 2020 à 17:21 | Mis à jour le 16 sept. 2020 à 8:39

Quelle est votre évaluation de la dynamique du Covid-19 en Europe ?

Nous avons bénéficié d’un répit estival bienvenu, mais constatons effectivement depuis peu une circulation exponentielle du virus en France, Espagne, Royaume-Uni, Autriche, Suisse, etc. Ce qui peut s’expliquer en partie par une politique de tests très intense, sans précédent historique. La notion de nouveaux « cas » manque par ailleurs d’une définition précise, puisqu’elle mêle aujourd’hui des malades plus ou moins symptomatiques et sévères, des cas contagieux mais asymptomatiques, ainsi que des personnes positives au test PCR dans les muqueuses nasales, mais avec une charge virale insuffisante pour les rendre contagieux. Pour autant, la hausse des hospitalisations en France et en Espagne nous oblige à envisager un scénario inquiétant, qui serait le résultat d’un « ensemencement » du virus sur tout le territoire, après une première phase d’émergence de « clusters ».

La fameuse deuxième vague ?

Plus précisément, nous sommes peut-être en train d’observer les fondements de ce qui deviendra une deuxième vague. Ce scénario d’une seconde vague plus homogène sur le territoire et peut-être l’Europe entière impose de s’y préparer, de mettre sur la table toutes les mesures nécessaires s’il survenait à l’automne.

Dans un autre scénario, plus optimiste, au vu du fait que, par ailleurs, cette flambée n’est pas observée partout en Europe, l’épidémie pourrait continuer à se propager seulement sous la forme de clusters, contrôlables tant que l’infection restera limitée aux jeunes de moins de 40 ans, lesquels développent très rarement des complications graves. Ce scénario s’il perdurait tout l’hiver permettrait de faire face comme cet été en Europe sans mesures trop contraignantes.

Comment expliquez-vous le décalage paradoxal entre flambée de cas et stagnation des décès partout en Europe, sauf dans quelques régions ?