#worldpolicyconf son président Thierry de Montbrial croit à valeur et service de la neutralité , Suisse bien commun humanité

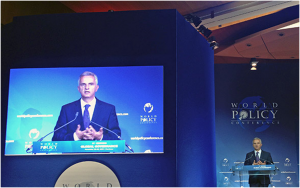

TWEET – With Swiss MFA at WorldPolicyConf

With Swiss MFA #Burkhalter at #WorldPolicyConf. Glad that our 2011 deal on OSCE brought our relations to a new level

TWEET – A few words on the Balkans

A few words on the Balkans, at the margins of #WorldPolicyConf in Montreux https://youtu.be/v0F0M6q_R90 via @YouTube

TWEET – CIRSD President interview

CIRSD President Vuk Jeremic gave an interview during #WorldPolicyConf in Montreux https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v0F0M6q_R90&feature=youtu.be …

Address by Governor Mugur Isărescu during the plenary session – The future of central banking

20.11.15

World Policy Conference, the 8th edition, 20-22 November 2015, Montreux, Switzerland

Parts of this address have been presented by Governor Mugur Isărescu during the plenary session “The future of central banking”, which also featured as speakers:

- Jean-Claude Trichet – former President of the European Central Bank

- Jacob Frenkel – Chairman of JPMorgan Chase International, former Governor of the Bank of Israel

- Marek Belka – President of the National Bank of Poland

– as prepared for delivery –

Ladies and gentlemen,

It is a great honour to address the audience during this symposium on the future of central banking, although I must confess from the very beginning that the topic itself is not easy to tackle. We all know that economists seldom reach a consensus when analysing the past. It is all the more difficult for them to agree on the future, especially when we refer to central bankers, who are known to be among the most cautious economists…

Personally, I think I have enough reasons to be wary of any predictions of what is in store for us, particularly over the medium and long term. I started my career as an economist in a research institute back in August 1971, when the Bretton Woods System was just collapsing. In 1990, shortly after the fall of communism, I became Governor of the National Bank of Romania, having to put into practice the transition from a monobank-type system to a two-tier system, while the country’s economy was going through major changes from the ruinous central planning to a market economy. As a matter of fact, in retrospect, I can say that my entire career has spanned several decades marked by truly ground-breaking policy and paradigm shifts. Some of the recent ones, such as quantitative easing and close to zero or even negative monetary policy rates, would have been inconceivable even a few years (not decades) before they occurred!

The experience acquired through the years, both as a researcher and as governor, makes me reluctant to engage in speculations on the future of central banking in 10 or 20 years’ time, particularly at the current juncture when the global economy is in a state of flux. Nevertheless, there are a few old and new things about central banking which I believe will continue to be relevant in the future.

I would start by pointing out that, in the extremely complex post-crisis economic and financial environment, the mission of a central bank cannot be simple. There are so many transformations going on right now, after the global crisis not only invalidated certain elements of mainstream economics, but also changed the order of priorities on policymakers’ agenda.

Still, I do not believe the crisis has shattered the consensus on what central banks should be pursuing – central banking has always been about the preservation of, to quote Charles Goodhart, “the three aspects of stability”, namely price stability, (external) currency stability and financial stability. Nor has the crisis brought about the sudden realisation that these aspects of stability do in fact condition each other – central bankers, maybe even more so emerging-market central bankers, have long been keenly aware that failure to ensure one kind of stability is bound to jeopardise the achievement of the others. What the crisis has indeed challenged is the widespread conviction that meeting one particular stability criterion, while necessary in order to achieve the others, is also a sufficient condition to do so – after all, maintaining price stability, while valuable in itself, has proved insufficient to ward off major financial or macroeconomic instability. As a matter of fact, Andrew Crockett claimed ever since 2003 that the “peace dividend” yielded by the successful war against inflation had not lived up to expectations and therefore the battlefront against financial instability should not be overlooked.

Nevertheless, it is widely accepted that price stability should remain the overriding objective of a central bank and I do not see this approach changing in the future, at least in Europe. It is expected, however, that central banks will make more explicit their concern for all the “three aspects of stability” in their policy decisions, realising that price stability and financial stability are much more intertwined than we used to think. I believe this development has farther-reaching consequences when it comes to the future of central banking. I can easily imagine, some years down the road, a more “normal” world in which unconventional monetary policy tools are a thing of the past, since their relevance is ultimately circumstantial, but I cannot imagine a future where the explicit concern for financial stability and the macroprudential policy are not central banking fixtures.

To be frank, the NBR has never had the luxury of being concerned exclusively with price stability and interest rate setting in the belief that financial stability and exchange rate stability will follow. In a world with freely moving capital, the idea of being able to manage aggregate demand exclusively via interest rates would have been an illusion: the interest rate hikes required to manage aggregate demand and anchor expectations would have entailed further capital inflows and an unsustainable nominal appreciation, thus boosting foreign currency lending and creating vulnerabilities on the financial stability front.

That is why, when introducing inflation targeting in 2005, the NBR opted for the “light” version of the strategy, which meant retaining the managed float feature of the exchange rate regime. The actual form inflation targeting took in Romania thus matched the “managed-floating plus” concept introduced by Goldstein in 2002, considered the most suitable choice for an emerging-market economy involved in the global capital market, as it combines the managed float part, allowing for FX market interventions in order to smooth out excessive volatility, with an inflation targeting monetary policy strategy and an active pursuit of measures to limit the degree of currency mismatches in the economy.

What are the challenges of adding explicit concern about financial stability to the standard objective of price stability? Should monetary policy lean against the wind sooner and possibly harder than it would normally? Even though now, with the benefit of hindsight, one could say that higher interest rates in the run-up to the crisis may have alleviated some of the issues that led to it, I believe that it is best to let monetary policy focus on price stability and deal with the objective of financial stability via dedicated macroprudential policy instruments – doing otherwise is likely to severely complicate communication with the public, complicating expectations management and ultimately undermining monetary policy credibility and effectiveness.

It is indeed of critical importance to make sure that the tasks entrusted to the central bank are feasible. Not as clear-cut or simple as before the global crisis, but feasible! Otherwise, if the monetary authorities are overburdened with possibly conflicting goals, the major risk is to render them inefficient and unable to deliver a single one of their objectives.

Before the crisis, when talking about the policy mix anyone would think of the coordination between monetary and fiscal policies. Afterwards, when financial instability has undermined macroeconomic stability, despite low and stable inflation, it became obvious that additional tools are needed in complementing monetary policy in countercyclical management. As macro-prudential tools emerged as the most important candidates, it makes sense to assign the objective of financial stability to the central bank, if the central bank is given control of the supervisory and regulatory instrument.

In the recent period some economists have asserted that central banks tend to fuel speculative bubbles by keeping monetary policy rates too low. This behaviour can create incentives for banks to overleverage or reduce efforts in screening borrowers, or can lead other economic agents to seek more risks in order to yield higher returns. The effects are likely to be worse if monetary policy is too accommodative for too long during expansions. This led to the conclusion that other instruments, which can directly affect leverage or risk taking, are required.

Because the cost of cleaning up after an asset-price bubble burst can be very high, as proved by the recent financial crisis, early interventions by the central bank might be needed when a severe bubble is identified. In this context, macro-prudential instruments are the best option, without excluding de plano the recourse to monetary policy instruments.

Given the fact that the policy rate is an inadequate tool to deal with overleverage, excessive risk taking, or apparent deviations of asset prices from fundamentals, there are other instruments at the policymaker’s disposal: countercyclical regulatory tools. Thus, if leverage appears excessive, regulatory capital ratios can be increased; if liquidity appears too low, regulatory liquidity ratios can be introduced and, if needed, increased; to dampen housing prices, loan-to-value ratios can be decreased; to limit stock price increases, margin requirements can be increased.

As I said earlier, the NBR has always had to juggle the “three aspects of stability” and that called for the deployment of alternative instruments, such as the full use of the reserve requirement ratios and recourse to administrative measures. Reserve requirement ratios were increased up to 20 and 40 percent for lei- and forex-denominated liabilities respectively, and the list of administrative measures included: enforcing a maximum loan-to-value ratio, introducing debt service ceilings relative to households’ monthly disposable income, setting limits on banks’ forex exposure vis-à-vis unhedged borrowers, using differentiated coefficients in stress tests (higher for exposures to EUR than lei, with even stricter coefficients for CHF- and USD-denominated credit).

Even though at the time our modus operandi was seen as deviating from the orthodoxy of central banking, during the global crisis or in its aftermath, macroprudential instruments are now part of the mainstream and forex interventions re-entered the arsenal of many central banks, including some of those using a free floating regime before the crisis.

If the importance of macro-prudential instruments was revealed by the global crisis and the forex interventions of central banks went back in fashion during the same period, there is a fact well known from the conventional economic wisdom, but highlighted once again by the crisis: the countercyclical stance of both monetary and fiscal policies is essential for ensuring a smooth trajectory of the economy. We all saw how unsustainable public finances and high levels of debt have impeded the effectiveness of a stability-oriented monetary policy. This was also the case of Romania, where the fiscal impulse was positive during the period of rapid growth before the financial crisis, contributing to the overheating of the economy and fuelling the imbalances accumulated in the economy. Moreover, the pro-cyclicality of the fiscal policy during the pre-crisis period exhausted the fiscal space needed to stimulate the economy in recession, leading to the need to reduce the budget deficit during the crisis (primarily due to financing constraints) and to perpetuating the pro-cyclicality of fiscal policy. As stated by Fritz Zurbrügg (2012), successful monetary policy is predicated on healthy fiscal policy, and vice versa, and to achieve stability and prosperity in the long term, fiscal and monetary policies must both focus on sustainability.

In the past, the high fiscal deficit has resulted in the fiscal dominance of monetary policy with its inevitable monetisation of the government debt, but nowadays most central banks no longer directly finance government expenditure. Today, this kind of dominance is manifested through the inability or unwillingness of fiscal authorities to control long-run expenditure/GDP ratio.

The recent period has outlined a different form of dominance: financial dominance, defined as the inability or unwillingness of the financial sector to absorb its losses. The presence of financial dominance constrains the manoeuvre room of both fiscal and monetary policies, due to the fact that fiscal authorities and/or central banks have to bail-out the financial sector. As pointed out by Benoît Cœuré (2015), for monetary policy, the problem stems mostly from inadequate supervision, at both micro-level (if supervisors show too much forbearance to under-capitalised banks, they can end up effectively shifting the burden onto monetary policy) and at macro-level (if supervisory policies allow banks to grow too rapidly, and then deleverage too slowly, it can also push the central bank into doing more), which can turn out in the ineffectiveness of monetary policy transmission mechanism.

Let me say a few words about the issues of central bank independence in the context of required cooperation with the government in the post-crisis world. As we all know, from a historical perspective the prevalence of central bank independence is a relatively new institutional development, seen as a solution to the problem of time inconsistency of monetary policy and the stagflation of the ’70s. Is the post-crisis reality likely to dissolve the consensus about central bank independence? After all, the danger of inflation is hardly a pressing concern nowadays (but rather the lack of it) and the pursuit of financial stability is ultimately a shared responsibility, since it implies close cooperation with the government and other authorities and may ultimately involve recourse to public funding.

I share Stanley Fisher’s view that it would be a costly mistake to give up central bank independence. That would mean “the benefits of having a central bank that can take a longer term and apolitical view of what is good for the economy and take actions in support of that view will be lost”. If a long-term perspective and a shield against political pressure are required for achieving price stability, these may be even more important if explicit concern for financial stability is added. And frankly, I do not see the need for close cooperation with the government as something that implies abandoning central bank independence, but rather as a pre-requisite – which has always been there – for promoting effective policies. Irrespective of how well-designed the policies of the central bank may be, they cannot substitute for a consistent macroeconomic policy mix, and in the absence of this consistency they are likely to achieve at best sub-optimal outcomes.

Having said that, I think there are a few questions worth asking – I must confess I do not have the answers, but I believe that the future of central banking hinges upon them.

- Would it be necessary to promote a certain tactical flexibility in the conduct of monetary policy, so that central banks might carry out adjustments in terms of objectives as well, not only instrument-wise? Such an approach would diminish the predictability of monetary policy, but would allow, when need be, for financial stability considerations to prevail over the inflation objective.

- Is the reassessment of the desirable level of inflation suitable? How low is too low? The same as for capital inflows, we can ask ourselves in the case of price stability as well: how much of a good thing is too much?

- Will the policy instruments which have been resorted to in the context of the global crisis become an integral part of the new conventional framework? If macroprudential tools are here to stay, the future of non-conventional monetary policy instruments is less certain. Will the central banks keep using these instruments or will they abandon them at some point in time? I fully share the belief of the Governor of Banco de España Luis Linde (2013) that monetary policy – conventional or not – cannot solve the ultimate causes behind the loss in investors’ confidence or the tensions in financial or banking markets; in fact, its main role is to provide time to adopt the necessary measures to reform and/or adjust.

- How much room for trade-off among different goals is available? I believe that we should try to learn as much as possible from the past mistakes. And I refer here not only to the recent past! The lessons of the last 7 years, while important, should not make us forget the lessons of the last 50 years, among which, to name but three, are the following:

- Accommodating other objectives should not put in danger price stability on the medium-run;

- Inflation expectations cannot be ignored;

- The independence of central banks is connected with their performance in delivering price stability.

Irrespective of how we see now the future of our profession and institutions, it is apparent that the central bankers cannot afford to live in an ivory tower. They have to stay open-minded and to keep close contact with the shifting economic and financial reality in order to be able to articulate and implement efficient policies. And if you still want me to foretell the future, I will end my speech by making a prophecy: what a central bank can or cannot do will remain a topic of heated debate for many decades.

20-22 November 2015

References

Cœuré, B., “Independence and Interdependence in a Monetary Union”, Lamfalussy Lecture Conference organised by Magyar Nemzeti Bank in Budapest, 2 February, 2015.

Crockett, A., “International Standard Setting in Financial Supervision”, Lecture at the Cass Business School, City University, London, February 5, 2003

Goodhart, C., “The Changing Role of Central Banks”, BIS Working Papers No 326, 2010

Goldstein, M., “Managed Floating Plus and the Great Currency Regime Debate”, Institute for International Economics Policy Analyses in International Economics, No. 66, 2002

Linde, Luis M., “The Changing Role of Central Banks”, the 4th Future of Banking Summit, organised by Economist Conferences, Paris, 26 February, 2013.

Zurbrügg, F., “Fiscal and Monetary Policy – Interdependence and Possible Sources of Tension”, the University of Lucerne, Lucerne, 21 November, 2012.

«Pour bien tourner, le monde a besoin d’un nouvel équilibre» (fr)

20.11.2015

Montreux, 20.11.2015 – Address by the Federal Councillor Didier Burkhalter on the occasion of the World Policy Conference in Montreux – Check against delivery

Monsieur le Président,

Mesdames et Messieurs,

Merci de votre invitation ! Et merci de votre présence en Suisse.

Il y a une semaine, la France a été atteinte au cœur, à Paris. La France, notre voisine – par la géographie et par les valeurs. La France, à l’égard de laquelle nous ressentons ici beaucoup d’amitié, une amitié solide, longue ; très longue, même, puisque nous célébrerons l’an prochain les cinq cents ans de notre traité de « paix perpétuelle »…

Les attaques de ces derniers temps ont été porté contre la liberté, l’égalité, les droits de l’homme ; contre les valeurs fondamentales de l’humanité. A Paris, comme à Beyrouth, au Sinaï, à Yola au Nigéria, à Bagdad ou ailleurs encore…

Il est des moments difficiles dans la vie ; dans celle des êtres humains comme dans celle des Etats. Il faut alors faire face, debout et unis.

La Suisse condamne avec la plus grande fermeté ces actes de barbarie. Elle partage la douleur des pays touchés, de leurs gouvernements et des proches des victimes. Nous ne céderons pas aux intimidations terroristes et sommes déterminés à travailler encore plus dur pour protéger nos populations et défendre les valeurs fondamentales de l’humanité. A nos yeux, il faut donner la première priorité à la prévention de l’extrémisme violent.

Aujourd’hui, notre monde est devenu plus instable, plus complexe, plus dangereux. La résurgence de la violence armée – des conflits violents et du terrorisme – affecte toutes nos sociétés. Elle engendre d’immenses souffrances humaines et compromet la sécurité et la prospérité dans le monde. Une barrière de feu s’est embrasée sur les flancs Sud et Est de l’Europe qui allume des foyers jusqu’au cœur de notre continent.

Ces crises sont un défi pour des régions entières, par l’afflux de réfugiés qui fuient cette violence et les brasiers qui consument leurs maisons. Des millions de personnes ont fui la Syrie, dont l’immense majorité se trouve dans les pays voisins de celle-ci. En Jordanie, par exemple, où nous essayons d’aider ; en revitalisant des écoles : 220’000 enfants Syriens se trouvent en Jordanie, 120’000 sont pour l’heure scolarisés, dans des conditions souvent difficiles, serrés parfois jusqu’à 80 par classe, se rendant à l’école le ventre creux. 100’000 autres enfants sont pour l’heure privés d’accès à l’éducation, et donc potentiellement privés de perspectives, d’un avenir : une bombe à retardement de plus…

Une minorité de ces réfugiés – mais tout de même des centaines de milliers – se tournent vers l’Europe, mettant celle-ci au défi : quelles réponses humaines, logistiques et sécuritaires ? Comment garder la maîtrise des risques et l’adéquation aux valeurs ?

Ceci dit, il n’y a pas que les conflits et le terrorisme qui occupent les chancelleries de nos jours. Une deuxième dynamique se dessine clairement : le retour de la géopolitique.

Ces deux facteurs conjugués – la géopolitique et la violence armée – marquent notre monde d’une empreinte profonde. Depuis un quart de siècle au moins, c’est la mondialisation qui façonne le destin du monde ; et cette grande tendance perdurera. Mais ces deux éléments – la géopolitique et la violence armée – redéfinissent les contours de cette mondialisation, avec une incidence nette sur la politique étrangère.

Dans notre monde du XXIe siècle, les crises ne sont plus l’exception mais la normalité. C’est en soi inacceptable – et il faut le combattre – mais on ne saurait nier l’évidence. Face à cela, le besoin de diplomatie atteint un niveau inégalé depuis de nombreuses années. Il faut de la diplomatie au pouvoir, et avant tout de la diplomatie créative !

Car la situation est sombre aujourd’hui. Nous vivons des temps d’incertitude et les gouvernements fonctionnent en mode de crise quasi permanent. La force du dialogue et la créativité de la diplomatie peuvent changer les choses. Et la Suisse peut apporter des contributions utiles à cet effet. Cette région lémanique et cette ville de Montreux, qui nous accueillent aujourd’hui, en sont un symbole et une réalité.

De nombreuses conférences de paix et rencontres diplomatiques, publiques ou discrètes, ont eu lieu sur les rives de ce lac. Jusque dans cet hôtel-même, où s’est tenue au début de l’an dernier la 2e conférence de paix sur la Syrie. La Suisse a une histoire et un rôle spécifiques. Elle se sent d’autant plus responsable de cette spécificité, tout en étant pleinement solidaire du monde.

C’est au fond de cela dont je souhaite vous parler : les changements du monde et la réponse de la Suisse.

Commençons par un zoom arrière pour observer un peu mieux cette grande tendance structurelle qu’est la mondialisation. Le principal effet de la mondialisation est de diffuser le pouvoir. Depuis la fin de la guerre froide, lorsqu’on a cru que les rideaux de fer appartenaient définitivement au passé de ce continent, le processus de globalisation a transformé le monde, peut-être plus que tout autre phénomène.

L’interconnexion économique, sociale et technologique croissante du monde a renforcé le pouvoir de nombreux acteurs. C’est vrai pour les acteurs non étatiques comme les ONG, les sociétés multinationales et les mégapoles. Mais il y a aussi eu un basculement du pouvoir presque monopolisé par les économies développées vers les économies émergentes et en développement du Sud et de l’Est.

Les écarts de développement entre les pays du monde se sont resserrés. Le nombre de personnes vivant dans l’extrême pauvreté dans les pays en développement est tombé de 47% en 1990 à 14% aujourd’hui. Nous sommes donc passés, en vingt-cinq ans, d’une personne sur deux à une personne sur sept !

Mais il y a le revers de la médaille. La mondialisation a également favorisé de nouvelles inégalités. Le progrès économique demeure inégal. C’est en Chine et en Inde qu’a eu lieu l’essentiel du recul de la pauvreté, tandis que l’Afrique subsaharienne reste encore à la traîne.

La diffusion rapide des idées, des biens et des capitaux ainsi que l’accélération des mouvements de population peuvent par ailleurs accentuer l’instabilité sociale, économique et politique. En Suisse, comme dans d’autres pays de l’OCDE, de nombreuses personnes s’inquiètent de l’immigration et de ses conséquences en termes de capacité d’intégration, d’aménagement d’un territoire déjà densément peuplé ou de compétition sur le marché de l’emploi. Les questions identitaires sont aujourd’hui un sujet politique majeur dans toute l’Europe.

La mondialisation peut être une force positive et offrir de formidables opportunités à l’humanité. Mais il faut la façonner de sorte à en maximiser les avantages et à en minimiser les inconvénients. Comme toujours, il faut chercher un point d’équilibre : la mondialisation ne peut pas progresser si elle est perçue comme un risque pour les sociétés, si elle va trop vite, si seule une minorité en tire avantage.

Faire progresser et non pas seulement avancer : c’est là la clé.

L’agenda de la mondialisation, c’est donc maintenir un ordre juste et pacifique ; c’est aussi veiller à l’efficacité et à la légitimité des institutions nationales et internationales ; c’est encore assurer la cohésion de nos sociétés. C’est enfin définir des réponses communes aux nombreux enjeux, qu’il s’agisse des menaces transnationales ou des défis globaux comme le climat, la sécurité, l’eau, les migrations, l’extrémisme violent.

Cette recherche d’un nécessaire équilibre, pour faire « bien tourner le monde » a toujours été un défi majeur. Il l’est d’autant plus aujourd’hui, en raison des deux évolutions que j’ai mentionnées: le retour de la géopolitique et la résurgence de la violence armée.

Le retour de la géopolitique est un effet secondaire de la mondialisation. Bien qu’un monde multipolaire ne soit pas nécessairement un obstacle à un multilatéralisme efficace, l’action collective est devenue plus complexe. Elle demande davantage d’engagement, de temps et d’énergie.

Or les grandes puissances semblent définir leurs intérêts davantage dans un esprit de confrontation que de coopération. Les normes internationales et le droit international sont l’objet de pressions croissantes.

La compétition géopolitique s’est amplifiée non seulement au niveau planétaire, mais aussi dans des contextes régionaux.

L’équilibre existant est remis en question dans plusieurs régions du monde, notamment en Asie de l’Est (avec les tensions dans la mer de Chine), en Europe (avec l’Ukraine) et au Moyen-Orient (dans une série de conflits). Dans toutes ces parties du monde, nous assistons à un bouleversement des équilibres régionaux et à la réémergence de nations qui avaient été de grandes puissances dans un passé parfois lointain, qui avaient marqué le monde au fil des siècles. Pensons au retour de la Chine ou de l’Inde, deux puissance qui détenaient la plus grande part du PIB mondial jusqu’au milieu du XIXe siècle, pensons à l’Iran, pensons à la Russie et à la Turquie, ces ponts entre l’Europe et l’Asie.

La géopolitique relève du choix des gouvernements, elle n’est pas un fait donné. Il nous appartient de démontrer que nous aurions tous avantage à choisir des solutions coopératives plutôt que des logiques d’exclusion.

Dans le dossier du nucléaire iranien, le pays concerné et les grandes puissances ont choisi la voie de la diplomatie plutôt que celle de la confrontation. La Suisse s’en réjouit et elle a fortement soutenu ce processus, qui s’est déroulé notamment dans cette région et – lui aussi, décidément… – dans cet hôtel.

Cet esprit de coordination et de dialogue – au-delà des divergences immédiates – parviendra-t-il à s’imposer également pour trouver une solution dans la crise syrienne ? La communauté internationale va-t-elle lutter efficacement et sur la base de décisions de l’ONU contre le soi-disant « Etat islamique » ?

L’avenir nous le dira. Mais le rétablissement du consensus, la reconstruction d’un ordre juste et pacifique demande aussi de reconnaître qu’il existe des limites à l’universalisme occidental, que la mondialisation – dirigée par l’Occident pendant plus d’un siècle – évolue vers la multipolarité.

La résurgence de la violence armée constitue un deuxième obstacle qui empêche d’avancer sur la voie du développement et de récolter les fruits de la mondialisation. Bien que des chercheurs nous rappellent que le nombre de conflits violents tend en fait à diminuer à long terme, nous devons relever deux phénomènes actuels :

Premièrement, le nombre de victimes est en forte progression. On estime que si les conflits violents ont fait 56’000 morts en 2008, ce nombre est passé à 180’000 en 2014. La guerre en Syrie a causé à elle seule la mort de 70’000 personnes l’an dernier. Selon le HCR à fin 2014, le monde comptait 60 millions de déplacés internes, un nombre inégalé depuis la fin de la Seconde Guerre mondiale !

Second phénomène : l’instabilité et la violence ont considérablement augmenté dans le voisinage même de l’Europe. A l’Est de l’Europe, la crise ukrainienne a marqué le retour de la guerre sur le continent, ce qui semblait impensable il y a peu. Au Sud, la situation s’est dégradée en de nombreux endroits. D’anciens conflits non résolus, comme le conflit israélo-palestinien, et des guerres plus récentes en Syrie, au Yémen, en Libye ont plongé la région dans une crise profonde. Et le terrorisme djihadiste progresse, favorisé par la défaillance des Etats.

Les effets du retour de la violence armée sont immenses : dans les régions en proie à des conflits, la sécurité humaine recule, l’activité économique est entravée – aujourd’hui les deux tiers de la population syrienne dépendent de l’aide humanitaire alors que plus de 4 millions de personnes ont fui le pays – et les progrès du développement sont réduits à néant.

L’Europe n’est pas non plus épargnée.

D’une part, elle doit faire face à un important afflux de réfugiés, qui cherchent à fuir cette violence. Elaborer une réponse appropriée à cette crise est devenue l’un des plus grands défis que l’Europe ait eu à relever ces dernières décennies.

D’autre part – et nous devons faire une claire distinction entre les deux sujets – l’Europe est devenue davantage la cible d’attaques terroristes. Avec les attaques de Paris, le terrorisme de « l’Etat Islamique » a pris une nouvelle dimension.

L’insécurité et l’instabilité qui prévalent au Moyen-Orient sont de plus en plus liées à la situation de l’Europe. La menace du terrorisme continuera par ailleurs sûrement de peser sur notre continent, même si nous mettons tout en œuvre pour la réduire.

Ladies and gentlemen

Where does Switzerland stand in this greater scheme of things?

Switzerland is a highly globalised country that has benefited from a stable and open global economy. According to several rankings, Switzerland figures among the ten most globalised countries worldwide, and has among the most innovative and competitive economies.

With its export-oriented, competitive, and innovative economy and its open society, it has benefitted significantly from the opportunities provided by globalisation.

This also means that our prosperity and security depend on a stable and open international environment.

Switzerland therefore has a strong interest in contributing to the search for cooperative solutions to these challenges. Our way forward lies in a continuing willingness to act, create and shape rather than in immobility. In our own interest, we would be badly inspired to opt for fear and self-confinement.

In the emerging multipolar world, Switzerland does not belong to one of the power centres. We are a European country promoting European values, and the EU is our most important partner. But Switzerland conducts its own foreign policy.

Our independence enables us to build bridges, to work with a broad range of partners, and to develop our own initiatives.

The more than 170 Swiss representations worldwide are a good basis for this.

In today’s world, Switzerland is not a small but a middle power. We are not so big as to frighten others. We are not part of any geopolitical power play. But neither are we too small to be heard and make an impact.

Switzerland belongs to the 20 biggest economies worldwide and ranks as number seven in Europe – and this despite a population that corresponds to that of a city like Paris!

Switzerland is the 15th biggest contributor to the UN regular budget. And we are leaders in innovation, not just in technology and business – but we do also try to conduct an innovative diplomacy!

Swiss foreign policy mirrors characteristics of our domestic political culture – this is its inner strength. We promote dialogue and a culture of compromise. We stand for inclusive solutions, for power-sharing arrangements, for human rights and humanitarian principles, for taming the powerful through law.

This explains that Switzerland has been able – with its different languages and religions – to “keep the peace” along the centuries.

I am convinced that these principles and values are more relevant than ever. Based on this we can – and will – do more.

So, what is Switzerland’s response to the current global changes? How do we engage? Let me make four points:

– We are addressing the refugee crisis

– We are enhancing our efforts to resolve conflicts, fight terrorism and promote peace and security

– We factor the need for peace into our development agenda

– And, for all the preoccupation with crisis management, we preserve space and capacity to contribute to efforts to advance the implementation of the globalisation agenda.

First, the refugee crisis: It has taken on dimensions unimaginable just months ago. This has become another major crisis that must be urgently dealt with – on top of everything else. The challenge is both political and moral. While it is telling that the refugees seek to flee to liberal democracies in the North, these liberal democracies – we in Europe – must now demonstrate our ability to come up with a joint response based on solidarity, the Geneva Conventions and effective implementation of the measures we have agreed.

Switzerland has given shelter to more than 9,000 Syrians since the outbreak of the war. We are working closely with the EU on addressing the refugee crisis on our continent. Switzerland participates in the relocation scheme. We are also contributing to EU efforts to better secure Europe’s borders, providing both financial and personnel resources.

Reflecting Switzerland’s humanitarian tradition, priorities in recent months has been to rapidly make available more humanitarian assistance for refugees in the conflict-affected regions – before winter sets in. But international efforts are still insufficient and more will be necessary in the months to come.

Second point: Switzerland is stepping up its commitment to peace and security. This will be reflected in the Federal Council’s Foreign Policy Strategy for the coming four years, which we are currently elaborating. Containing, de-escalating and resolving the many crises and reducing the level of armed violence has become one of the key tasks of our time.

Over the past fifteen years, Switzerland has developed a unique set of instruments to transform conflicts, protect civilians in conflicts, and advance human security.

As chair of the Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) last year, we demonstrated that thanks to its unique role, Switzerland can make useful contributions to defuse crises.

One of the fields we want to expand is our mediation capacity. Mediation is what Switzerland is particularly good at, and mediation is what is particularly needed on the international stage these days. We will broaden and further professionalise our pool of mediators and experts to consolidate our leading role in this field. And we will continue to offer our services to facilitate peace talks, in International Geneva or elsewhere.

Another key field is obviously terrorism. Two months ago, the Swiss Government approved a national strategy to counter terrorism. It is based on the four pillars of prevention, law enforcement, protection and crisis management provisions.

Prevention is a major focus, and we strengthen it in two major ways: First, with a new Intelligence Service Act that has now passed Parliament (but may still be up to a referendum). Second, we have made the prevention of violent extremism a new priority issue within Swiss foreign policy. Providing those vulnerable to violent extremism with alternative opportunities is a tremendous task. Development and peace promoting measures must be applied for counterterrorist purposes: from youth employment to the promotion of political participation by actors who can speak credibly to young people at risk. We are in the process of devising our first action plan on preventing violent extremism. Working with the UN in this field will be an important part.

Let me give your three examples how we engage in the field of preventing violent extremism:

i) First we promote international cooperation and norm-building on this issue. The UN is expected to present its first Plan of Action of Prevent Violent Extremism by the end of this year. Switzerland will co-host in the spring of next year an international conference in Geneva to discuss the implementation of this action plan. Building such a common roof for the international community is essential for effective action against violent extremism.

ii) Second Switzerland runs its own projects on the ground. Our country is fortunate to have one of the lowest youth unemployment rates in Europe. This is due in large parts to our vocational education and training system that facilitates the integration of youth into the labour market and provides the economy with the skills that are needed. In several countries such as Tunisia or Afghanistan, Switzerland is contributing to vocational training projects. We are convinced that offering real perspectives to young people is key to preventing them from turning towards violent extremism. As we announced at the leader’s summit on the prevention of violent extremism in New York two months ago, Switzerland will host an expert-level meeting on professional training next year in Geneva. The meeting will be focussing on the role vocational training can play in creating perspectives and foster resilience in regions particularly at risk with regard to violent extremism.

iii) Third Switzerland also supports substantially the Global Community Engagement and Resilience Fund (GCERF). This is a public-private initiative based in Geneva that was established to serve as the first global effort to support local, community-level initiatives aimed at strengthening resilience against violent extremism. The GCERF is about to announce concrete projects in Bangladesh, Mali and Nigeria. We encourage both public and private actors to support the GCERF.

Such measures will mainly have mid- and long-term effects.

By far the most important short-term priority to reduce armed violence and advance security is to end the war in Syria:

– This would give Syrians a chance to rebuild their country.

– This would give the displaced a perspective of returning home.

– This would also improve the prospects of diminishing IS.

Switzerland supports the efforts of UN Special Envoy de Mistura to foster intra-Syrian dialogue. We can help with expertise and, if required, with financial resources and Geneva logistics. Any political transition must be Syrian-led and Syrian-owned. But it is important that the regional and world powers create an enabling environment. In this regard, it is encouraging that the US and Russia, despite all their differences, have now established a Syria Support Group, with Saudi-Arabia and Iran sitting at the same table.

Switzerland calls on all actors involved to translate their shared solidarity expressions over the Paris attacks into a concrete common effort to stop the violence in Syria. Only then is there a chance to make progress towards the declared objective of credible, inclusive, non-sectarian governance, with a new constitution and free and fair elections.

Our third response to the current global changes concerns what I have just hinted at: The ever more obvious nexus between development and armed violence. There can be no development without peace, and no peace without development.

This has been acknowledged by the new framework for international cooperation, the Agenda 2030. “Peaceful and inclusive societies” is one of 17 Sustainable Development Goals.

If we want to further reduce poverty, advance sustainable development and prevent violent extremism, we must transform fragile states into peaceful, inclusive and stable states. This is quite easy to say…! It requires a lot of work. Beginning by complementing traditional development activities with peace- and state-building measures. Today, half of Switzerland’s development partners are fragile states. Addressing the causes of their fragility, increasing their crisis resistance and improving their human rights situation will be an ever more important objective in the years ahead. It is challenging although necessary.

This brings me to the fourth and final point of Switzerland’s response to the current developments: While my country can – and must – contribute to managing the current crises, advancing the globalisation agenda must remain a priority. We must be careful not to forget these long term goals while we invest time and energy in the management of the crises. I am thinking of our contributions to the debate on reforming the United Nations and of our ideas to strengthen the OSCE’s capacity to act; of our efforts to promote cooperative security in East Asia and the Middle East; of our engagement for non-proliferation and disarmament; of our joint initiative with the ICRC to strengthen compliance with international humanitarian law; or of our Programmes to address themes such as climate change,

food security, migration, and water.

In our eyes water must be a topic for cooperation, not an issue for war – this is why we launched an international panel on water and peace last Monday in Geneva.

Ladies and Gentlemen,

Once again, I would like to thank you to be here in Switzerland.

I would like to thank you to be here to debate common challenges with regard to our community on this planet.

Dialogue, diplomacy, creativity: we need all of this; and gatherings such as this “World Policy Conference” builds precisely on them.

In the face of common challenges, in this quest for a new equilibrium, I think that Switzerland, the spirit of this region, the spirit of Geneva – a spirit of peace and cooperation – can help and inspire us all.

I wish you a warm welcome, a nice day and every success in your work!

Address for enquiries

Information FDFA

Bundeshaus West

CH-3003 Bern

Tel.: +41 58 462 31 53

Fax: +41 58 464 90 47

E-Mail: info@eda.admin.ch

Publisher

Federal Department of Foreign Affairs

http://www.eda.admin.ch/eda/en/home/recent/media.html

Didier Burkhalter prône la prévention de l’extrémisme violent

20.11.2015

LUTTE ANTITERRORISTE – Didier Burkhalter veut donner la priorité à la prévention de l’extrémisme violent. Le conseiller fédéral a rappelé l’importance de ne pas céder aux intimidations de l’EI.

“Il faut donner la première priorité à la prévention de l’extrémisme violent”, a plaidé Didier Burkhalter vendredi. Revenant sur les attentats de Paris il y a une semaine, le conseiller fédéral a rappelé l’importance de ne pas céder aux intimidations terroristes.

“Nous sommes déterminés à travailler encore plus dur pour protéger nos populations et défendre les valeurs fondamentales de l’humanité”, a déclaré M. Burkhalter, selon le texte écrit de son allocution. Il s’exprimait à l’ouverture de la réunion annuelle de la World Policy Conference (WPC) à Montreux (VD), une organisation qui réfléchit aux moyens d’améliorer la gouvernance sous tous ses aspects.

Le chef de la diplomation suisse a réitéré sa ferme condamnation pour des “actes de barbarie”. Il a rappelé d’autres attaques récentes “contre la liberté, l’égalité, les droits de l’homme”: “à Beyrouth, au Sinaï, à Yola au Nigeria, à Bagdad ou ailleurs encore”…

Avant de disserter sur la plus grande complexité et instabilité du monde, Didier Burkhalter a souligné la très longue amitié entre la Suisse et la France. Il a rappelé que “nous célébrerons l’an prochain les cinq cents ans de notre traité de ‘paix perpétuelle'”.

«Pour bien tourner, le monde a besoin d’un nouvel équilibre»

20.11.2015

Allocution du Conseiller fédéral Didier Burkhalter lors de la World Policy Conference à Montreux – Seul le texte prononcé fait foi

Orateur: Chef du Département, Didier Burkhalter

DFAEMonsieur le Président,

Mesdames et Messieurs,

Merci de votre invitation ! Et merci de votre présence en Suisse.

Il y a une semaine, la France a été atteinte au cœur, à Paris. La France, notre voisine – par la géographie et par les valeurs. La France, à l’égard de laquelle nous ressentons ici beaucoup d’amitié, une amitié solide, longue ; très longue, même, puisque nous célébrerons l’an prochain les cinq cents ans de notre traité de « paix perpétuelle »…

Les attaques de ces derniers temps ont été porté contre la liberté, l’égalité, les droits de l’homme ; contre les valeurs fondamentales de l’humanité. A Paris, comme à Beyrouth, au Sinaï, à Yola au Nigéria, à Bagdad ou ailleurs encore…

Il est des moments difficiles dans la vie ; dans celle des êtres humains comme dans celle des Etats. Il faut alors faire face, debout et unis.

La Suisse condamne avec la plus grande fermeté ces actes de barbarie. Elle partage la douleur des pays touchés, de leurs gouvernements et des proches des victimes. Nous ne céderons pas aux intimidations terroristes et sommes déterminés à travailler encore plus dur pour protéger nos populations et défendre les valeurs fondamentales de l’humanité. A nos yeux, il faut donner la première priorité à la prévention de l’extrémisme violent.

Aujourd’hui, notre monde est devenu plus instable, plus complexe, plus dangereux. La résurgence de la violence armée – des conflits violents et du terrorisme – affecte toutes nos sociétés. Elle engendre d’immenses souffrances humaines et compromet la sécurité et la prospérité dans le monde. Une barrière de feu s’est embrasée sur les flancs Sud et Est de l’Europe qui allume des foyers jusqu’au cœur de notre continent.

Ces crises sont un défi pour des régions entières, par l’afflux de réfugiés qui fuient cette violence et les brasiers qui consument leurs maisons. Des millions de personnes ont fui la Syrie, dont l’immense majorité se trouve dans les pays voisins de celle-ci. En Jordanie, par exemple, où nous essayons d’aider ; en revitalisant des écoles : 220’000 enfants Syriens se trouvent en Jordanie, 120’000 sont pour l’heure scolarisés, dans des conditions souvent difficiles, serrés parfois jusqu’à 80 par classe, se rendant à l’école le ventre creux. 100’000 autres enfants sont pour l’heure privés d’accès à l’éducation, et donc potentiellement privés de perspectives, d’un avenir : une bombe à retardement de plus…

Une minorité de ces réfugiés – mais tout de même des centaines de milliers – se tournent vers l’Europe, mettant celle-ci au défi : quelles réponses humaines, logistiques et sécuritaires ? Comment garder la maîtrise des risques et l’adéquation aux valeurs ?

Ceci dit, il n’y a pas que les conflits et le terrorisme qui occupent les chancelleries de nos jours. Une deuxième dynamique se dessine clairement : le retour de la géopolitique.

Ces deux facteurs conjugués – la géopolitique et la violence armée – marquent notre monde d’une empreinte profonde. Depuis un quart de siècle au moins, c’est la mondialisation qui façonne le destin du monde ; et cette grande tendance perdurera. Mais ces deux éléments – la géopolitique et la violence armée – redéfinissent les contours de cette mondialisation, avec une incidence nette sur la politique étrangère.

Dans notre monde du XXIe siècle, les crises ne sont plus l’exception mais la normalité. C’est en soi inacceptable – et il faut le combattre – mais on ne saurait nier l’évidence. Face à cela, le besoin de diplomatie atteint un niveau inégalé depuis de nombreuses années. Il faut de la diplomatie au pouvoir, et avant tout de la diplomatie créative !

Car la situation est sombre aujourd’hui. Nous vivons des temps d’incertitude et les gouvernements fonctionnent en mode de crise quasi permanent. La force du dialogue et la créativité de la diplomatie peuvent changer les choses. Et la Suisse peut apporter des contributions utiles à cet effet. Cette région lémanique et cette ville de Montreux, qui nous accueillent aujourd’hui, en sont un symbole et une réalité.

De nombreuses conférences de paix et rencontres diplomatiques, publiques ou discrètes, ont eu lieu sur les rives de ce lac. Jusque dans cet hôtel-même, où s’est tenue au début de l’an dernier la 2e conférence de paix sur la Syrie. La Suisse a une histoire et un rôle spécifiques. Elle se sent d’autant plus responsable de cette spécificité, tout en étant pleinement solidaire du monde.

C’est au fond de cela dont je souhaite vous parler : les changements du monde et la réponse de la Suisse.

Commençons par un zoom arrière pour observer un peu mieux cette grande tendance structurelle qu’est la mondialisation. Le principal effet de la mondialisation est de diffuser le pouvoir. Depuis la fin de la guerre froide, lorsqu’on a cru que les rideaux de fer appartenaient définitivement au passé de ce continent, le processus de globalisation a transformé le monde, peut-être plus que tout autre phénomène.

L’interconnexion économique, sociale et technologique croissante du monde a renforcé le pouvoir de nombreux acteurs. C’est vrai pour les acteurs non étatiques comme les ONG, les sociétés multinationales et les mégapoles. Mais il y a aussi eu un basculement du pouvoir presque monopolisé par les économies développées vers les économies émergentes et en développement du Sud et de l’Est.

Les écarts de développement entre les pays du monde se sont resserrés. Le nombre de personnes vivant dans l’extrême pauvreté dans les pays en développement est tombé de 47% en 1990 à 14% aujourd’hui. Nous sommes donc passés, en vingt-cinq ans, d’une personne sur deux à une personne sur sept !

Mais il y a le revers de la médaille. La mondialisation a également favorisé de nouvelles inégalités. Le progrès économique demeure inégal. C’est en Chine et en Inde qu’a eu lieu l’essentiel du recul de la pauvreté, tandis que l’Afrique subsaharienne reste encore à la traîne.

La diffusion rapide des idées, des biens et des capitaux ainsi que l’accélération des mouvements de population peuvent par ailleurs accentuer l’instabilité sociale, économique et politique. En Suisse, comme dans d’autres pays de l’OCDE, de nombreuses personnes s’inquiètent de l’immigration et de ses conséquences en termes de capacité d’intégration, d’aménagement d’un territoire déjà densément peuplé ou de compétition sur le marché de l’emploi. Les questions identitaires sont aujourd’hui un sujet politique majeur dans toute l’Europe.

La mondialisation peut être une force positive et offrir de formidables opportunités à l’humanité. Mais il faut la façonner de sorte à en maximiser les avantages et à en minimiser les inconvénients. Comme toujours, il faut chercher un point d’équilibre : la mondialisation ne peut pas progresser si elle est perçue comme un risque pour les sociétés, si elle va trop vite, si seule une minorité en tire avantage.

Faire progresser et non pas seulement avancer : c’est là la clé.

L’agenda de la mondialisation, c’est donc maintenir un ordre juste et pacifique ; c’est aussi veiller à l’efficacité et à la légitimité des institutions nationales et internationales ; c’est encore assurer la cohésion de nos sociétés. C’est enfin définir des réponses communes aux nombreux enjeux, qu’il s’agisse des menaces transnationales ou des défis globaux comme le climat, la sécurité, l’eau, les migrations, l’extrémisme violent.

Cette recherche d’un nécessaire équilibre, pour faire « bien tourner le monde » a toujours été un défi majeur. Il l’est d’autant plus aujourd’hui, en raison des deux évolutions que j’ai mentionnées: le retour de la géopolitique et la résurgence de la violence armée.

Le retour de la géopolitique est un effet secondaire de la mondialisation. Bien qu’un monde multipolaire ne soit pas nécessairement un obstacle à un multilatéralisme efficace, l’action collective est devenue plus complexe. Elle demande davantage d’engagement, de temps et d’énergie.

Or les grandes puissances semblent définir leurs intérêts davantage dans un esprit de confrontation que de coopération. Les normes internationales et le droit international sont l’objet de pressions croissantes.

La compétition géopolitique s’est amplifiée non seulement au niveau planétaire, mais aussi dans des contextes régionaux.

L’équilibre existant est remis en question dans plusieurs régions du monde, notamment en Asie de l’Est (avec les tensions dans la mer de Chine), en Europe (avec l’Ukraine) et au Moyen-Orient (dans une série de conflits). Dans toutes ces parties du monde, nous assistons à un bouleversement des équilibres régionaux et à la réémergence de nations qui avaient été de grandes puissances dans un passé parfois lointain, qui avaient marqué le monde au fil des siècles. Pensons au retour de la Chine ou de l’Inde, deux puissance qui détenaient la plus grande part du PIB mondial jusqu’au milieu du XIXe siècle, pensons à l’Iran, pensons à la Russie et à la Turquie, ces ponts entre l’Europe et l’Asie.

La géopolitique relève du choix des gouvernements, elle n’est pas un fait donné. Il nous appartient de démontrer que nous aurions tous avantage à choisir des solutions coopératives plutôt que des logiques d’exclusion.

Dans le dossier du nucléaire iranien, le pays concerné et les grandes puissances ont choisi la voie de la diplomatie plutôt que celle de la confrontation. La Suisse s’en réjouit et elle a fortement soutenu ce processus, qui s’est déroulé notamment dans cette région et – lui aussi, décidément… – dans cet hôtel.

Cet esprit de coordination et de dialogue – au-delà des divergences immédiates – parviendra-t-il à s’imposer également pour trouver une solution dans la crise syrienne ? La communauté internationale va-t-elle lutter efficacement et sur la base de décisions de l’ONU contre le soi-disant « Etat islamique » ?

L’avenir nous le dira. Mais le rétablissement du consensus, la reconstruction d’un ordre juste et pacifique demande aussi de reconnaître qu’il existe des limites à l’universalisme occidental, que la mondialisation – dirigée par l’Occident pendant plus d’un siècle – évolue vers la multipolarité.

La résurgence de la violence armée constitue un deuxième obstacle qui empêche d’avancer sur la voie du développement et de récolter les fruits de la mondialisation. Bien que des chercheurs nous rappellent que le nombre de conflits violents tend en fait à diminuer à long terme, nous devons relever deux phénomènes actuels :

Premièrement, le nombre de victimes est en forte progression. On estime que si les conflits violents ont fait 56’000 morts en 2008, ce nombre est passé à 180’000 en 2014. La guerre en Syrie a causé à elle seule la mort de 70’000 personnes l’an dernier. Selon le HCR à fin 2014, le monde comptait 60 millions de déplacés internes, un nombre inégalé depuis la fin de la Seconde Guerre mondiale !

Second phénomène : l’instabilité et la violence ont considérablement augmenté dans le voisinage même de l’Europe. A l’Est de l’Europe, la crise ukrainienne a marqué le retour de la guerre sur le continent, ce qui semblait impensable il y a peu. Au Sud, la situation s’est dégradée en de nombreux endroits. D’anciens conflits non résolus, comme le conflit israélo-palestinien, et des guerres plus récentes en Syrie, au Yémen, en Libye ont plongé la région dans une crise profonde. Et le terrorisme djihadiste progresse, favorisé par la défaillance des Etats.

Les effets du retour de la violence armée sont immenses : dans les régions en proie à des conflits, la sécurité humaine recule, l’activité économique est entravée – aujourd’hui les deux tiers de la population syrienne dépendent de l’aide humanitaire alors que plus de 4 millions de personnes ont fui le pays – et les progrès du développement sont réduits à néant.

L’Europe n’est pas non plus épargnée.

D’une part, elle doit faire face à un important afflux de réfugiés, qui cherchent à fuir cette violence. Elaborer une réponse appropriée à cette crise est devenue l’un des plus grands défis que l’Europe ait eu à relever ces dernières décennies.

D’autre part – et nous devons faire une claire distinction entre les deux sujets – l’Europe est devenue davantage la cible d’attaques terroristes. Avec les attaques de Paris, le terrorisme de « l’Etat Islamique » a pris une nouvelle dimension.

L’insécurité et l’instabilité qui prévalent au Moyen-Orient sont de plus en plus liées à la situation de l’Europe. La menace du terrorisme continuera par ailleurs sûrement de peser sur notre continent, même si nous mettons tout en œuvre pour la réduire.

Mesdames et Messieurs,

Où est la Suisse dans cette nouvelle configuration du monde ?

La Suisse est un pays fortement mondialisé, bénéficie d’une économie mondiale stable et ouverte. A en croire plusieurs classements, la Suisse figurerait parmi les dix pays les plus mondialisés et dispose d’une des économies les plus innovantes et compétitives.

Cette société et économie compétitive, innovante et axée sur l’exportation a grandement bénéficié des opportunités déroulantes de la globalisation.

Cela signifie aussi que notre prospérité et notre sécurité dépendent d’un environnement international stable et ouvert.

La Suisse a donc un intérêt important à contribuer à la recherche de solutions coopératives à ces défis. La clé de notre avenir réside dans la volonté constante d’agir, de créer et de façonner plutôt que dans l’immobilité. C’est dans notre propre intérêt de ne pas nous laisser entrainer par la peur et le repli sur soi.

Dans ce monde multipolaire émergent, la Suisse n’appartient à aucun des centres du pouvoir. Nous sommes un pays européen qui promeut des valeurs européennes, et l’UE est notre principal partenaire. Mais la Suisse mène sa propre politique étrangère. Notre indépendance nous permet de jeter des passerelles, de travailler avec un large éventail d’acteurs et de développer nos propres initiatives. Les plus de 170 représentations suisses implantées dans le monde offrent à cet égard de bonnes possibilités.

Dans le monde d’aujourd’hui, la Suisse n’est pas une petite mais une moyenne puissance. Nous ne sommes pas assez grands pour effrayer les autres. Nous ne participons à aucun jeu de pouvoir géopolitique. Mais nous ne sommes pas pour autant trop petits pour être entendus et avoir une influence. La Suisse compte parmi les 20 premières économies mondiales et se classe au septième rang au niveau européen – alors que sa population correspond à celle d’une ville comme Paris ! Par ailleurs, elle est le 15e contributeur au budget ordinaire de l’ONU. Et nous sommes des champions en innovation, pas seulement dans les technologies et les affaires, mais nous tentons également de mener une diplomatie innovante !

La politique extérieure de la Suisse reflète les caractéristiques de notre culture politique nationale – c’est au fond ce qui fait sa force. Nous encourageons le dialogue et une culture du compromis. Nous sommes pour les solutions fédératrices, pour les formules de partage du pouvoir, pour les droits de l’homme et les principes humanitaires, pour la primauté du droit sur le pouvoir. Voilà aussi ce qui explique comment la Suisse, avec ses différentes langues et religions – est parvenue à préserver la paix au fil des siècles.

Je suis convaincu que ces principes et valeurs sont plus importants que jamais. En nous basant sur eux, nous pouvons faire davantage et nous le ferons.

Donc, quelle réponse la Suisse apporte-t-elle aux changements à l’œuvre dans le monde ? Comment nous mobilisons-nous ?

Permettez-moi de rappeler quatre points :

– Nous travaillons à résoudre la crise des réfugiés

– Nous intensifions nos efforts pour régler les conflits, lutter contre le terrorisme et promouvoir la paix et la sécurité

– Nous intégrons la nécessité de la paix dans notre programme de développement

– Et, quelles que soient les préoccupations liées à la gestion de crise, nous veillons à disposer de la marge et de la capacité nécessaires pour contribuer aux efforts destinés à faire progresser la mise en œuvre de l’agenda de la mondialisation.

Premièrement, la crise des réfugiés : elle a pris des dimensions qui auraient été inimaginables il y a seulement quelques mois. Cette nouvelle crise majeure doit être traitée de toute urgence – en plus de tout le reste. Le défi est à la fois d’ordre politique et d’ordre moral. Fait significatif, les réfugiés cherchent à fuir vers les démocraties libérales du Nord, et ces démocraties libérales– c’est-à-dire nous, en Europe – doivent démontrer leur capacité à apporter une réponse commune à la crise qui soit fondée sur la solidarité, sur les Conventions de Genève et sur la mise en œuvre effective des mesures convenues.

La Suisse a donné refuge à plus de 9000 Syriens depuis le déclenchement de la guerre. Nous coopérons étroitement avec l’UE pour faire face à la crise des réfugiés sur notre continent. La Suisse participe au programme de relocalisation. Nous contribuons également aux efforts de l’UE visant à sécuriser les frontières européennes, en lui fournissant des ressources financières et humaines.

Conformément à la tradition humanitaire de la Suisse, la priorité a été, ces derniers mois, d’augmenter rapidement l’aide humanitaire fournie aux réfugiés dans les régions affectées par le conflit – avant l’arrivée de l’hiver. Mais les efforts internationaux restent insuffisants et il faudra les intensifier dans les mois qui viennent.

Deuxièmement, la Suisse renforce son engagement en faveur de la paix et de la sécurité. C’est ce qui ressortira de la stratégie de politique étrangère du Conseil fédéral pour les quatre prochaines années, que nous élaborons actuellement. Endiguer, désamorcer et résoudre les nombreuses crises en cours et réduire la violence armée sont devenues des missions clés de notre temps.

Au cours des quinze dernières années, la Suisse a mis au point une panoplie unique d’instruments permettant de transformer les conflits, de protéger les civils dans les conflits et de promouvoir la sécurité humaine. En exerçant la présidence de l’Organisation pour la sécurité et la coopération en Europe (OSCE) l’année dernière, nous avons montré que grâce à son rôle unique, la Suisse peut utilement contribuer à désamorcer les crises.

L’un des champs d’activité que nous souhaitons développer est notre capacité de médiation. La Suisse a des aptitudes particulières pour la médiation, et il y a actuellement une forte demande en la matière sur la scène internationale. Nous élargirons notre pool de médiateurs et d’experts et professionnaliserons leur formation afin de consolider notre rôle de premier plan dans ce domaine. Et nous continuerons à offrir nos services pour faciliter les pourparlers de paix, à Genève ou ailleurs.

Le terrorisme constitue évidemment un autre domaine clé. Il y a deux mois, le gouvernement suisse a approuvé une stratégie nationale de lutte contre le terrorisme. Elle repose sur quatre piliers : la prévention, la répression, la protection et la gestion des crises.

La prévention est une priorité et nous la renforçons essentiellement de deux manières : D’abord, nous avons élaboré une nouvelle loi sur le renseignement, qui a maintenant été approuvée par le Parlement (mais qui reste sujette à référendum).

Deuxièmement, nous avons érigé la prévention de l’extrémisme violent en nouvelle priorité de la politique extérieure de la Suisse. Une tâche énorme consiste à offrir des possibilités aux personnes vulnérables comme alternatives au terrorisme violent. Le développement et la promotion de la paix ont un rôle à jouer dans la lutte contre le terrorisme. Diverses mesures doivent être prises notamment en matière d’emploi des jeunes et d’encouragement à la participation politique, en faisant intervenir des personnes pouvant s’adresser de manière crédible aux jeunes à risques. Nous sommes en train d’élaborer notre premier plan d’action pour la prévention de l’extrémisme violent. La collaboration avec l’ONU dans ce domaine occupera une place de choix en la matière.

J’aimerais vous donner trois exemples pour l’engagement de la Suisse dans la prévention de l’extrémisme violent :

i) Par la promotion de la coopération internationale. L’ONU va annoncer avant la fin de l’année son premier plan d’action pour la prévention de l’extrémisme violent. La Suisse co-organisera au printemps prochain une conférence internationale à Genève afin de débattre de la mise en œuvre de ce plan d’action. Bâtir un toit commun pour notre communauté internationale – voilà qui est essentiel pour combattre efficacement le terrorisme violent.

ii) Deuxièmement, la Suisse réalise des projets sur le terrain. Notre pays a l’un des taux de chômage des jeunes parmi les plus bas en Europe. Cela est dû en grande partie à la formation professionnelle duale qui facilite l’intégration de la jeunesse dans le marché du travail et qui fournit à l’économie les qualifications et aptitudes dont celle-ci a besoin. La Suisse contribue dans plusieurs pays à des projets de formation professionnelle, comme par exemple en Tunisie ou en Afghanistan. Nous sommes convaincus que la clé pour dissuader les jeunes de se tourner vers le terrorisme consiste à leur offrir de réelles perspectives de vie. La Suisse a annoncé, il y a deux mois, lors du leader’s summit on the prevention of violent extremism à New York qu’elle allait organiser l’année prochaine une rencontre d’experts sur la formation professionnelle à Genève. La rencontre sera axée sur la question du rôle que la formation professionnelle peut jouer pour créer des perspectives et favoriser la résilience des sociétés dans des régions du globe particulièrement menacées par l’extrémisme violent.

iii) Troisièmement, la Suisse soutient aussi substantiellement le Global Community Engagement and Resilience Fund (GCERF). Il s’agit d’une initiative globale, à caractère publique-privée et basée à Genève établie dans le but de soutenir les efforts locaux des communautés pour favoriser leur résilience à l’encontre de l’extrémisme violent. Le GCERF va prochainement annoncer des projets concrets au Bangladesh, au Mali et au Nigéria. Nous encourageons les acteurs privés et publics à soutenir le GCERF.

Il est clair que de telles mesures, tout comme le renforcement de nos capacités de médiation, auront essentiellement des effets à moyen et à long terme. A court terme, mettre un terme à la guerre en Syrie est certainement la priorité la plus importante pour réduire la violence armée et promouvoir la sécurité. Cela donnerait aux Syriens une chance de reconstruire leur pays et aux personnes déplacées une perspective de retour chez elles. Par ailleurs, les chances d’affaiblir l’EI s’en trouveraient améliorées.

La Suisse soutient les efforts déployés par l’envoyé spécial des Nations Unies Staffan de Mistura en faveur du dialogue inter-syrien. La Suisse peut aider en lui apportant son expertise et, si nécessaire, en mettant à sa disposition des moyens financiers et la logistique genevoise. Si toute transition politique doit être conduite et contrôlée par la Syrie, il est important que les puissances régionales et globales créent un environnement favorable. A cet égard, il est encourageant de voir que, en dépit de toutes leurs divergences, les Etats-Unis et la Russie ont maintenant créé un Groupe international de soutien à la Syrie, qui réunit autour d’une même table l’Arabie saoudite et l’Iran.

La Suisse appelle tous les acteurs impliqués à traduire leurs manifestations de solidarité après les attaques de Paris en un effort commun pour mettre fin à la violence en Syrie. C’est la seule chance de progresser dans la réalisation de l’objectif déclaré d’une gouvernance crédible, inclusive, non confessionnelle, suivie par une nouvelle Constitution et des élections libres et équitables.

Notre troisième réponse aux changements à l’œuvre dans le monde concerne un sujet que j’ai juste effleuré, à savoir la corrélation toujours plus évidente entre le développement et la violence armée. Il ne peut y avoir de développement sans paix, ni de paix sans développement.

Cela a été reconnue dans l’Agenda 2030, le nouveau cadre pour la coopération internationale, qui fait de la promotion de « sociétés pacifiques et inclusives » l’un des 17 objectifs de développement durable.

Si nous voulons réduire encore la pauvreté et faire progresser le développement durable ainsi que prévenir l’extrémisme violent, nous devons œuvrer à la transformation des Etats fragiles pour en faire des Etats pacifiques, inclusifs et stables. C’est facile à dire… ! Cela requiert beaucoup de travail, à commencer en complétant les activités de développement traditionnelles par des mesures de consolidation de la paix et de renforcement de l’Etat. Aujourd’hui, la moitié des partenaires de développement de la Suisse sont déjà des Etats fragiles. Dans les années qui viennent, il sera d’autant plus important de s’attaquer aux causes de leur fragilité, de renforcer leur résistance aux crises et d’améliorer leur situation en matière de droits de l’homme. C’est un défi mais il est nécessaire de le relever.

J’en arrive ainsi au quatrième et dernier point en ce qui concerne la réponse de la Suisse aux développements en cours. Mon pays peut et doit contribuer à la gestion des crises actuelles, mais une priorités doit être aussi de faire progresser l’agenda de la mondialisation. Nous devons faire attention de ne pas perdre de vue ces buts à long terme alors que la gestion de crise absorbe beaucoup de temps et d’énergie.

Je pense à nos contributions au débat sur la réforme des Nations Unies et à nos idées concernant le renforcement de la capacité d’action de l’OSCE ; à nos efforts en vue de promouvoir la sécurité coopérative en Asie de l’Est et au Moyen-Orient ; à notre engagement en faveur de la non-prolifération des armes et du désarmement ; à notre initiative conjointe avec le CICR sur le renforcement du respect du droit international humanitaire ; ou à nos programmes portant sur des questions comme le changement climatique, la sécurité alimentaire, la migration et l’eau.

A nos yeux, l’eau doit faire l’objet de coopération, pas de conflits armés. Voilà pourquoi nous avons lancé lundi passé à Genève un panel international sur la thématique de l’eau et de la paix.

Mesdames et Messieurs,

Une fois encore, j’aimerais vous remercier d’être ici en Suisse ; et surtout d’être ici pour débattre des enjeux communs, de notre vie commune sur cette planète. Du dialogue, de la diplomatie, de la créativité : tout cela est nécessaire et des rencontres telles que cette « world policy conference » s’inscrivent dans ce mouvement.

Et face à ces enjeux communs, dans cette recherche de nouvelle équilibre, je pense que la Suisse, l’esprit de cette région, l’esprit de Genève – un esprit de paix et de coopération – peut nous aider et nous inspirer.

Alors bienvenue, bonne journée et bon travail

Contact

Information DFAE

Palais fédéral ouest

CH-3003 Berne

Tél.: +41 58 462 31 53

Fax: +41 58 464 90 47

E-Mail: info@eda.admin.ch

Editeur:

Didier Burkhalter prône la prévention de l’extrémisme violent

20.11.2015

LUTTE ANTITERRORISTE – Didier Burkhalter veut donner la priorité à la prévention de l’extrémisme violent. Le conseiller fédéral a rappelé l’importance de ne pas céder aux intimidations de l’EI.

Le conseiller fédéral Didier Burkhalter ce vendredi à la World Policy Conference à Montreux. (Photo d’archive) KEYSTONE“Il faut donner la première priorité à la prévention de l’extrémisme violent”, a plaidé Didier Burkhalter vendredi. Revenant sur les attentats de Paris il y a une semaine, le conseiller fédéral a rappelé l’importance de ne pas céder aux intimidations terroristes.

“Nous sommes déterminés à travailler encore plus dur pour protéger nos populations et défendre les valeurs fondamentales de l’humanité”, a déclaré M. Burkhalter, selon le texte écrit de son allocution. Il s’exprimait à l’ouverture de la réunion annuelle de la World Policy Conference (WPC) à Montreux (VD), une organisation qui réfléchit aux moyens d’améliorer la gouvernance sous tous ses aspects.

Le chef de la diplomation suisse a réitéré sa ferme condamnation pour des “actes de barbarie”. Il a rappelé d’autres attaques récentes “contre la liberté, l’égalité, les droits de l’homme”: “à Beyrouth, au Sinaï, à Yola au Nigeria, à Bagdad ou ailleurs encore”…

Avant de disserter sur la plus grande complexité et instabilité du monde, Didier Burkhalter a souligné la très longue amitié entre la Suisse et la France. Il a rappelé que “nous célébrerons l’an prochain les cinq cents ans de notre traité de ‘paix perpétuelle'”.

Antonio Trombetta

Ambassador of Argentina to Switzerland since 2013. Previously, he served as Chief of Staff of the Minister of Foreign Affairs (2010-2013) and Director, North America Department (2008-2010). He also worked within the Ministry of Economy and Production (2006-2007). From 1999 to 2005, he was Head of the section for Economy and Trade at the Embassy of Argentina to the EU. He was also General Consul of Argentina in Zurich (1997-1999). Lawyer, he graduated from the University of Buenos Aires.

Jaromir Sokolowski

Ambassador of Poland to Switzerland since 2015. Previously, he served as Undersecretary of State for International relations at the Chancellery of the President of Poland (2010-2015). He was also Acting Director General of the Speaker of Sejm (Lower Chamber of the Parliament) (2007-2010). From 2005 to 2007, he was Advisor to the Deputy Speaker of Sejm. He was also a freelance journalist (2003-2007). He graduated from Warsaw University and the University of Hamburg.

Gabriela von Habsburg

Professor at VADS, Free University, Tbilisi since 2014. She is also a Senior Fellow at GISS Georgian Institute for Strategic Studies since 2013. Previously, she served as Ambassador of Georgia to Germany (2009-2013) and as Professor at the State Academy of Arts in Tbilisi (2001-2009). She studied Philosophy and Arts at the Ludwig Maximilian University Munich and at the Academy of Arts in Munich.

Julien Steimer

Chief executive of AXA South West France. Before joining AXA France in 2013, he served the French government for over a decade in the areas of diplomacy and politics, European Union, agriculture policy reform and global food security. He was Chief of staff of the French Ministers of European Affairs and then of Food and Agriculture. He graduated from the Ecole Nationale d’Administration (ENA) and Sciences Po Paris. He is Yale World Fellow 2012 and Young Global Leader 2014.

Kelvin Tan

Deputy Director, Monetary Authority of Singapore. He is the Secretary General (Southeast Asia) and Board member of the Africa-South East Asia Chambers of Commerce (ASEACC), based in Singapore. Previously, he served as a Senior Investment Officer at the International Finance Corporation (IFC), a member of the World Bank Group. Prior to IFC, he was Deputy Director of the Emerging Markets Division of the Ministry of Trade and Industry (MTI). Specific to Africa, he has visited over 10 countries in Sub Saharan Africa and played a key role in formulating Singapore’s economic strategies for Africa.

Boro Bronza

Ambassador of Bosnia and Herzegovina to Switzerland since 2013. Previously, he served as Ambassador of Bosnia and Herzegovina to Greece (2009-2013). He is also a Visiting professor at the Department for History, Faculty of Philosophy, University of Banja Luka since 2009. He was also a Senior assistant professor at the Department for History, Faculty of Philosophy, University of Banja Luka (2006-2009) and assistant professor at the Department for History, Faculty of Philosophy, University of Banja Luka (2001-2006). He holds a PhD from the University of Banja Luka.

Wolfgang Amadeus Bruelhart

Ambassador, Head Middle East and North Africa Division, Swiss Foreign Ministry since 2012. Previously, he served as Ambassador of Switzerland to the United Arab Emirates (2008-2012), Head of Human Rights Policy Section and Head of the Task Force “Human Rights Council” at the Department of Foreign Affairs (2003-2007) and Cultural Counsellor at the Swiss Embassy in London (1992-2002). He was also a Counsellor at the Swiss Embassy in Sarajevo (1996-1998).

Kerry Halferty Hardy