TOKYO — Russia’s aggression against Ukraine is graphic and brutal evidence of the international community’s inability to effectively respond to events that disrupt peace. The U.N. Security Council is a distressing symbol of this paralysis.

The Security Council is supposed to play the role of « the guardian of peace » and has the authority to do so. It can decide to slap sanctions on countries threatening peace, and U.N. member countries are required to comply with its decisions.

In response to Russia’s military action against its neighbor, the Security Council held an emergency meeting on Feb. 25 but could not even adopt a resolution to condemn the act, let alone sanctions against Moscow.

Russia, which vetoed the resolution, presided over the meeting as the rotating president of the council, an almost comical situation that showed the limits of the body’s effectiveness.

The five permanent members of the council — the U.S., Britain, France, China and Russia — have veto power to kill any resolution. There is no doubt that Moscow will keep using this privilege to torpedo any draft resolution to punish it for the invasion.

In this image made from video released by the Russian Presidential Press Service, President Vladimir Putin addressees the nation from Moscow on Feb. 24 after authorizing military action against Ukraine. (Russian Presidential Press Service via AP)

The impotence of the key U.N. body in the face of such a full-blown security crisis bodes ill for stability in the Asia-Pacific region. Consider the possibility of China invading Taiwan. It is all too clear that Beijing would use its veto power to prevent the council from taking any effective step to stop it.

North Korea fired missiles as many as nine times in 2022 alone. Pyongyang has also violated U.N. resolutions by firing ballistic missiles. So far this year, however, the Security Council has failed to adopt a resolution to condemn North Korea due to opposition from China and Russia.

These facts eloquently testify to the gloomy reality that the Security Council has lost its relevance. The council’s structure was created in October 1945, immediately after the end of World War II, under the leadership of the victorious U.S., Britain and the Soviet Union. China and France were also invited to join the exclusive club.

At that time, these five powers were expected to support the postwar world order. But this assumption has now collapsed completely. Russia has become a clear invader and China is more interested in bending the current order in its favor than protecting it.

The Security Council’s problem is nothing new. It did not work well during the Cold War. In 2003, the U.S., which many saw as the leader in maintaining the world order, opened a war against Iraq without a clear U.N. resolution to fully justify its action.

But the dismal performance of the council should not be used as an excuse for allowing the status quo to continue. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the most egregious act committed by a major power in the postwar period, should prod the world into a long-overdue move to fix the situation.

What should be done? Theoretically, there are two approaches — radical reform of the council’s structure or finding an alternative.

The former would be the orthodox way. The most desirable option is to establish certain limits to the veto power of the permanent members to prevent abuse by China or Russia.

But this would require amending the U.N. Charter, a step that must be approved by a vote of two-thirds of the U.N. General Assembly and all the permanent members of the Security Council. That means it is a tall order.

Besides China and Russia, the U.S., Britain and France are also against limiting their veto power, a highly valued privilege, though they do not say so openly, said a senior U.N. bureaucrat.

The next best option would be to increase both the permanent and nonpermanent members of the Security Council without touching the veto power of the five nations.

This could involve, for instance, giving permanent seats to some other major powers, such as Japan, Germany and India, or increasing the number of nonpermanent seats from the current 10. Advocates say this would increase pressure on China, Russia and other permanent members to refrain from abusing their power to shoot down resolutions.

The catch is that this step too would require revision of the U.N. Charter. Some countries have been calling for a major reform of the body, but Beijing and Moscow have balked even at including such calls and related discussions in official records, according to diplomatic sources at the Security Council.

A more plausible idea would be to strip Russia of its permanent member status as a way to punish it for the attack on Ukraine. Some Western democracies are moving to explore this option, according to European media.

Russia became a permanent member of the council as the successor to the Soviet Union, which collapsed in 1991. The advocates of Russia’s removal will likely try to find irregularities in the succession process that can be used as a reason to kick it out.

Russian Ambassador to the United Nations Vassily Nebenzia votes during a U.N. Security Council meeting on a resolution regarding Russia’s actions toward Ukraine on Feb. 25. © Reuters

Shinichi Kitaoka, a professor emeritus at the University of Tokyo who served as Japan’s ambassador and deputy permanent representative to the U.N. from 2004 to 2006, calls for the effective use of the General Assembly to put diplomatic pressure on the permanent members of the Security Council. « U.N. resolutions, even if they cannot produce immediate effects, can serve as a tool to demonstrate legitimacy to the international community, » he said. « In 2005, Japan, Germany, India and Brazil worked together to submit to the General Assembly a proposal to reform the Security Council to increase its membership. This is an example of how countries can use the assembly to promote changes to make it easier to put pressure on permanent members that have done something wrong. »

In addition to trying to revamp the Security Council itself, it is also vital to step up efforts to create a new system to do what the present structure cannot do. One specific idea that merits consideration is for countries that share the same values and views of freedom and the world order to forge a « coalition » to complement the functions of the council. Ryozo Kato, a former Japanese ambassador to the U.S., proposes to institutionalize the Group of Seven to ensure more solid and effective cooperation among the leading democracies to promote peace and stability.

In response to violations of international rules, the G-7 has taken joint actions such as issuing statements and imposing sanctions against the violators. However, it is only a voluntary grouping that lacks any institutional foundation.

It is crucial to « enable the G-7 to take stronger and more effective actions by establishing new principles and goals for cooperation and creating a permanent organization for its activity, » Kato said. « It would also be a good idea to expand the group by inviting other major democracies like Australia and India. Through such steps, the G-7 should become an organization that can support the proper functions of the Security Council. »

The U.N., of course, has many agencies and organizations that make important daily contributions to tackling such global challenges as sustainable development and humanitarian assistance as well as food, energy and environmental crises. But if the Security Council, which has enforcement powers, remains in tatters, there can never be stability in the world order. If Russia’s barbaric act does not lead to an overhaul of the body, the Security Council will never be able to change to become a true guardian of peace and order.

Read the original article on the site of Nikkei.

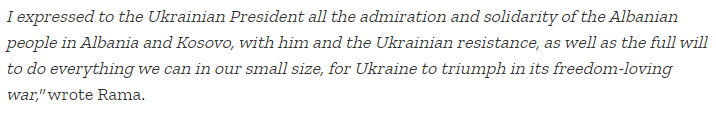

MADRID – Russian President Vladimir Putin’s barbaric war on Ukraine seems to have awakened Germany from its post-Cold War slumber, with a dramatic shift in foreign and defense policy indicating a newfound recognition of Russia’s unreliability as a partner and the broader security challenges Europe faces. But can Germany’s tougher approach withstand a painful and protracted crisis, or will accommodationist voices regain traction, urging acceptance of the realities on the ground?

There is no doubting the resoluteness of Germany’s response to the Russian invasion. Beyond halting the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline project, Chancellor Olaf Scholz has announced a €100 billion ($109 billion) increase in defense spending this year and agreed to send weapons – not just helmets – to Ukrainian fighters.

Moreover, Germany has participated in the imposition of sweeping Western sanctions aimed at isolating Russia and inflicting maximum economic pain. More fundamentally, Germany seems finally to have abandoned its long-held belief that dialogue is the only way to deal with the Kremlin.

Germany’s newfound mettle, which has been welcomed across Europe, was by no means guaranteed. For decades, Germany’s approach to geopolitics had emphasized rapprochement and economic engagement, with its Russia policy representing a kind of misguided continuation of the Federal Republic’s Cold War-era Ostpolitik. This persisted through Russia’s invasion of Georgia in 2008, its downing in 2014 of MH-17, a passenger flight passing over eastern Ukraine, and the Kremlin’s poisoning of political opponents like Alexei Navalny, who recovered from a nerve-agent attack in a German hospital.

Germany was not alone in taking a soft-handed approach to Russia. The United Kingdom has continually – and willingly – attracted Russian oligarchs’ dark money. In this sense, Britain’s sanctioning of oligarchs like Roman Abramovich also represents a notable shift.

But, historically, Germany has been at the center of Europe’s political tangles. This was often for the worse: Germany repeatedly disrupted Europe’s balance of power, leading to conflict and unparalleled bloodshed, culminating in World War II. But with the 1951 creation of the European Coal and Steel Community, which bound together Germany and France, the country’s role was transformed.

From Chancellor Konrad Adenauer’s tenure in the 1950s and early 1960s through Chancellor Helmut Kohl’s in the 1980s and 1990s, it was said that Germany would find its interests in the interests of the European project. Integration was the only conceivable path to a sustainable and lasting European peace, and Germany was essential to achieving that goal.

After reunification in 1990, Germany leveraged its economic strength and prowess to assume a unique convening power in Europe, which enabled it to define the EU’s agenda – and, thus, trajectory – for decades.

But Germany’s leadership was always selective. It used its influence – enhanced by an EU presidency – to press for the completion of an EU-China investment agreement just a month ahead of US President Joe Biden’s inauguration last year. (That deal is now in limbo, unlikely to be ratified by the European Parliament any time soon.) Germany also pushed forward Nord Stream 2, despite its allies’ concerns.

However, in areas that drew less German interest, such as banking union, the EU was left largely directionless. This dynamic is what prompted former Polish Foreign Minister Radosław Sikorski to declare in 2011 that he feared Germany’s power less than its inactivity. In fact, Germany’s selective leadership prevented the EU from forging ahead strategically and left it reliant on former Chancellor Angela Merkel’s personal mediation, which ended when her 16-year tenure did.

In this sense, Putin has done the West a favor. By launching a brutal and unprovoked invasion of Ukraine and threatening the West with nuclear escalation, he has shaken the very foundations of the postwar order – and jolted Germany out of its dream of Wandel durch Handel (change through commerce). If recent policy changes are any indication, a more comprehensive and strategic form of German leadership could emerge.

But the Western countries imposing costs on Russia will also face high costs, from low growth to skyrocketing energy bills. The post-pandemic recovery could be all but wiped out in much of Europe. Over time, this – together with the existential dread generated by Putin’s wanton nuclear threats – could generate significant pressure on European leaders to pursue normalization of relations with Russia and even greater accommodation of it. Germany’s coalition government will be no exception.

Putin would view any such shift as yet another demonstration of Western weakness, all but inviting him to pursue ever-bolder gambits. That is why the West, with Germany as a central player, must stand firm in defending its values and opposing Russia’s illegal aggression, despite the costs. Otherwise, sooner or later, we will find ourselves once again living in a world where, as the Athenian historian Thucydides famously put it, “the strong do what they can, and the weak suffer what they must.”

Read the original article on the site of Project Syndicate.