May 15, 2018

Uri Dadush, OCP Policy Center

Looming trade wars unsettle investors and endanger the global economic upswing. The long-term consequences of a withdrawal from global markets, were it to occur, would be much worse. Productivity growth, already low, could turn negative. Citizens would see inflationary pressures escalate with the price of imported products, and their living standards would decline. Large investments have been made in value chains that span the world and turning back would be enormously costly. To avoid this catastrophe, one must look beyond the policy drama in Washington and instead focus more closely on the underlying causes of the trade tensions. The fault lines of the world trading system were visible long before the arrival of Mr. Trump and his departure from the scene will not make them disappear. When his administration ends, whether in January 2024, January 2020 or sooner, truncated by his legal troubles, there may be a return to civility in trade relations, but not to normality.

Three facts should by now be evident: President Trump is a convinced protectionist; he is determined to use American power to exact concessions without regard to World Trade Organization (WTO) rules; and his trade policies bitterly divide Americans. While his base, mainly composed of less educated white male workers whose incomes have stagnated over decades, continues to support him, the domestic opposition to his protectionism is formidable. It consists of the export interests, such as farmers and the high-tech sectors, the retail and logistics firms that depend on imports, many firms that are heavy users of imported parts and raw materials and that are part of global value chains, export-oriented States, the (regrettably largely silent) Republican majority in Congress as well as many Democrats, and the near-totality of the economic and political commentariat.

The President’s bullying and his open disregard of these concerns makes it clear that appeasement will not work, and that he must be confronted – and sooner is better. Those who support his protectionism must be made to realize that tariffs will trigger retaliation and that they will result not only in higher prices for consumers, which initially will be small and diffuse, but also cause large job and profit losses to firms and groups that depend on exports. Put simply, the political cost of tariffs must exceed the political gain of imposing them. Only then will Mr. Trump be deterred from his irresponsible course.

As a free trader, I do not argue for a hard line lightly; In my view, it represents the course that is most likely to minimize the damage to the world trading system before it is too late. Nor does my espousal of a hard line mean that the United States is the only one responsible for the current impasse. The United States remains, even today, the world’s most open large economy, and the causes of trade tensions extend well beyond America. They run much deeper than Mr. Trump. In the next section, I attempt to identify the deeper causes of the disease.

Four Growing Challenges to The Trading System

The present trade tensions reflect four sets of problems, none of which are new, and none of which are amenable to a quick fix. In order of importance these problems are: the uneven sharing of the benefits from the current era of globalization and technological advance, especially but not only in the United States; Chinese exceptionalism; macroeconomic imbalances; and the dysfunction of the World Trade Organization (WTO). Each of these issues have been the object of extensive study, including dozens if not hundreds of academic papers, and they have also been the object of many reform attempts. Yet, while progress has been made in some areas, each issue remains, and the trends, unfortunately, are not promising.

Inequality. Much of the rise in inequality and the increased economic disruption, which stirs the discontent with globalization, is due to unskilled-labor-saving technology, not trade. However, the disruptive effects of trade and technology interact and reinforce each other in many ways: for example, cheaper transport and communication facilitate outsourcing and all forms of trade; and, firms which are confronted with new sources of low-cost competitors respond by automating and innovating. Technology facilitates trade, and trade prompts technology adoption. Separating the effect of these two powerful forces is hard and workers who are employed in sectors exposed to international competition and who lose their jobs naturally find it easier to blame foreigners than to blame robots. The largest disruptive effects of trade liberalization may be behind us, as trade is already largely free, and there does not appear to be another China about to rise (India is a candidate for the next great trade disruption but its likeliness is a distant and uncertain prospect). Hence, ironically, the next wave of job losses is just as likely to come from increased protectionism as opposed to deriving from the trade liberalization so reviled by the anti-globalists.

However, there is no sign that technology and the other forces driving increased inequality are slowing, on the contrary. Labor-saving technology (artificial intelligence, autonomous vehicles, etc.) is, according to a recent Mc Kinsey report and to others, already capable of displacing hundreds of millions of workers. Furthermore, in our globalized IT-driven economy, the returns to innovation tend to accrue to small groups of people. And the return to capital – whose ownership is highly concentrated – continues to outstrip the rate of growth of GDP by a wide margin, as argued by Tomas Piketty and confirmed by recent empirical studies. Though governments should be fighting these trends, the recent tax, spending and health-care reforms in the United States, which is the advanced country with the most unequal income distribution, do the opposite. The reforms benefit wealthy individuals and companies far more than they help the average American. Even though social spending in the United States is very low by the standards of other advanced countries, in coming years rising budget deficits will put even greater pressure to reduce it.

China. A great paradox and unprecedented feature of the current era is that the world’s largest exporter and manufacturer (the Chinese manufacturing sector is as large as that of the United States and Japan combined) remains a state-driven developing country. Even as its firms conquer world markets, China’s average tariffs are two to three times higher than those of the European Union, Japan, and the United States. Although many Chinese firms already operate at the cutting edge of technology, and China is increasingly enforcing intellectual property rights at home, it continues to be accused by scores of firms and observers across Europe and the United States of forcing technology transfer from foreign investors and to engage in widespread intellectual property theft. Although the share of State Owned Enterprises in China’s employment has declined sharply in past decades, it remains far higher than that of any large economy, and these enterprises are widely believed to benefit from preferential non-transparent credit awarded by the formal banking system which also remains state owned. As Chinese firms penetrate global markets with exports and, increasingly with acquisitions and greenfield investment, the differences between the Chinese system and that of its advanced country competitors have become an increasing source of friction.

On one crucial issue, China has changed. China’s current account surplus has declined massively, from around 10% of GDP a few years ago to a shade above 1% of GDP projected by the IMF for 2018. To this extent, China is making rapid progress towards a more balanced growth model, one that is less reliant on exports and more reliant on domestic demand. In fact, for countries around the globe China is well on its way to becoming their largest export market by a wide margin. However, given the economy’s large presence on world markets, its high investment rate and rapid growth as both importer and exporter, the tensions associated with Chinese exceptionalism are more likely to increase than abate. As the old saying goes, it is difficult to sleep next to an elephant, whichever way it turns.

Imbalances in designing the International Monetary Fund (IMF) at the end of World War 2, the great British economist John Maynard Keynes and his American counterpart Harry White had imbalances, and the risk they posed for international macroeconomic stability and the trading system, at the center of their preoccupations. Tensions over large current account deficits and surpluses are always present. However, in recent years, the dramatic narrowing of China’s current account surplus and of the United States’ deficit had taken some steam out of the issue. But China’s large bilateral trade surplus with the United States remained a source of tension, and President Trump’s obsession with bilateral imbalances – whose importance economists dismiss – has added a lot of fuel to the fire. Yet it is not at all clear what China could do to significantly and quickly reduce its bilateral trade surplus with the United States, an outcome that Trump’s negotiators are demanding.

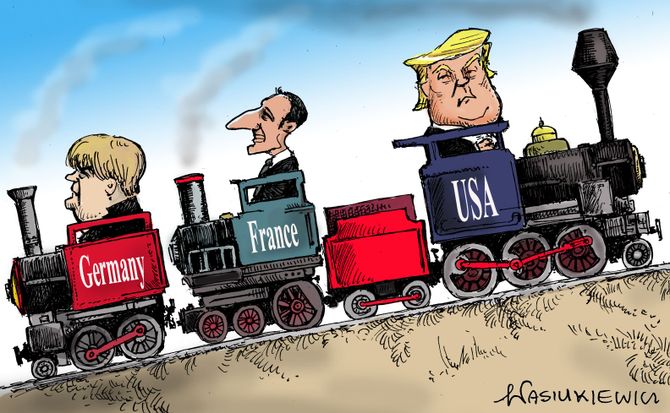

Germany’s very large current account surplus, which is nearly as big as that of China’s and Japan’s combined, is a more recent phenomenon, but it has become an equally important source of tension, not only with the United States but with other members of the Euro zone, especially the struggling countries of the South. To a significant degree, Germany’s surplus is the artificial result of the creation of the Euro – since had Germany retained the Deutsche Mark, it would almost certainly have seen a very large appreciation. It is true that Germany’s monetary, exchange rate and trade policies are in the hands of European institutions, so outside Germany’s direct control. But there is no sign as that Germany is prepared to undertake the increased government spending, higher wage policies, or tax reforms that would be needed to significantly dent its current account surplus and provide some relief to its Euro zone partners and help defuse trade tensions. Unfortunately, with the new tax and spending policies in the United States, the nation’s current account deficit is projected to widen again in coming years, spelling even more trouble in the future.

WTO. The institution which is the bedrock of the orderly, open and predictable trading system that emerged after World War 2 has – contrary to the popular narrative – registered significant successes since its establishment in 1995 as a follow-on to the GATT. Most notable are the expansion of its membership which now covers 98% of world trade (versus some 85% at inception), the Bali Trade Facilitation Agreement, the Government Procurement Agreement, the Information Technology Agreement and its extension, the prohibition of agricultural export subsidies, and of voluntary export restraints. However, the WTO’s incapacity to move forward on wide -ranging multilateral negotiations in the Doha agenda and to deal with many long-standing trade impediments, such as agricultural subsidies and barriers to services trade, and even less to take on new issues such as electronic commerce, has meant that its negotiating arm has fallen behind the times.

Its other major function, the dispute settlement system, has continued to be extensively used, but has come under increasing challenge, mainly from the United States, for “overreaching” and “gap-filling,” i.e. adjudicating on issues or in a way that goes beyond that which negotiators had agreed. All this preceded the arrival of Mr. Trump. Continuing a policy of the Obama administration, the United States is now refusing to replace the members of the Appellate Body of the WTO as their terms come due. This means that the Dispute Settlement system could effectively cease to function before the end of 2019. Moreover, three recent measures undertaken by the United States are almost certainly in violation of the WTO, namely the spurious appeal to national security in raising tariffs on steel and aluminum imports, the negotiation of voluntary export restraints on the same with Korea, and the section 301 action against China. Obviously, the effective demise of the Doha agenda, the flouting of WTO rules by its emblematic member and the United States’ increased reluctance to support its adjudication is bound to weaken it further. A de facto exit of the United States from the WTO leading to the organization’s demise or to a truncated WTO is no longer unthinkable.

This panoramic of the causes of the current trade tensions underscores the importance of a coordinated and broad-based approach in resolving them, such as could be undertaken by the G-20 context but looks distinctly unlikely at present. All this strongly suggests that things will get worse before they get better. Far from going away, the present challenges to the trading system are likely to become even more pressing in the future.

Drawing the Threads: Implications for Policy

Standing up to Mr. Trump is not easy. It risks escalation. But the greater risk is condoning polices which are likely only to result in more and more protectionism and which undermine the legal foundations of the present system. The Trump administration will end, perhaps sooner than later, and the next administration, whether Democrat of Republican is unlikely to be as disruptive or reckless as the current one. Even so, many of the trade concerns that are prevalent today will continue.

There is no easy solution to the issue of inequality and disruption caused by globalization and technology. Policy-makers must step up their efforts to explain the benefits of trade, while at the same time strengthening the mechanisms that protect the most vulnerable. However, there are limits to social assistance and the most promising long-term solutions are those that promote mobility of workers, which above-all means building skills and flexibility. In a forthcoming note prepared under the aegis of the T20, my co-authors and I have elaborated a set of proposals intended to mitigate the cost of adjustment to international trade shocks.

China must accelerate its market reforms, engage in more far-reaching trade liberalization and privatization, and take more aggressive measures to boost consumption. If it is, one day, to lead the reforms of the trading system, as its size and dynamism suggest it should, it must first resolve its internal contradictions. Germany must, for its own sake, enhance those of its Southern European partners, and for trade peace, increase public spending, raise its public sector and minimum wages, and encourage more domestic investment to bring down its current account surplus. The United States will sooner or later have to reverse its tax cuts on the wealthy to contain inequality and reverse its policy of fiscal stimulus to reduce its budget deficits. These measures will help contain the United States’ national overspending which lies at the root of its current account deficits.

The members of the WTO need to find ways to revitalize its negotiating arm – for example by undertaking multiple sectoral or plurilateral agreements. They should also prepare for a contingency where the United States effectively abandons the Dispute Settlement Understanding. At the same time, nations should accelerate their efforts to conclude bilateral and regional trade agreements that are complementary to the WTO. These agreements are very important in consolidating and deepening trade liberalization and can provide an insurance policy against a resurgence of protectionism. For example, members of the European Union, such as Belgium now conducts about 80% of their trade under regional and bilateral trade agreements.

As already said, trade tensions are likely to get worse before they get better. The current impasse may persist over many years, but my expectation (or perhaps more accurately, my hope) is that ultimately the international community will avoid a return to the trade wars of the 1930s and to the import substitution practiced in many parts of the world just a few decades ago. I do not base my cautious optimism on confidence in the capacity of policy-makers to deal comprehensively and rapidly with the issues – I expect that they will do what they can under severe political constraints and, at best, muddle through.

I base my hope on the forces that are pushing for a more integrated global economy, and which are becoming stronger with every passing day. The same information, communication and transportation technologies that are disrupting our societies are also bringing firms and consumers closer together irrespective of national borders. In addition, firms and consumers are more aware than ever of the opportunities of arbitrage across the world market in goods, services and capital. In such a world, it is increasingly difficult to separate free trade from individual freedom. History has shown again and again that those that choose to withdraw behind national borders in the face of the twin forces of markets and technology, sooner or later succumb to them.